Hunting with Pygmies

Cries of “Eeee-ay, Eeee-ay” echoed noisily around the forest. The hunt was in full swing. The hunters were making a lot of noise: the noise of chimpanzees, of gorillas, of elephant. The theory being that their prey, the blue duiker, would hear the noise and freeze in hiding. To move would be to make the duiker vulnerable. The hope is to flush the duiker out of hiding at a later stage. Well that at least is the theory when you hunt with the Ba’Aka in the Dzangha Sangha region of the south-western corner of the Central African Republic

The Ba’Aka pygmies (pronounced “Bye-acka”) are the original hunter-gatherers of the forest. Sadly their way of life has changed greatly in recent times and their age-old dress and customs are fading into the past. Logging, an industry which is set to double in the region in the next few years, has been partly responsible for such change. The network of logging roads that criss-cross the forest have opened up an area hitherto virtually inaccessible. These roads provide easy access to commercial hunters whose killing is on a much greater scale to the hunting of the Ba’Aka, which is for the pot and sustainable.

But although their way of life is evolving, the Ba’Aka still guard their rich inheritance and their knowledge of the forest has in no way diminished. For them, amongst other uses, the forest offers a rich pharmacopoeia of traditionally recognised medicinal properties. We were fortunate to be shown such variety by Essandja.

As I stumbled and struggled my way through the entangling trees and vines, Essandja would point out, pull out and explain the uses of a selection of plants, trees and shrubs, most of which looked the same to my untrained western eye. She showed us the green leaves from the Kuko vine, which is a rich source of protein in their diet. Parasites are treated with a tea of leaves from the Ingoka bush Thomanderisa hensii (for intestinal worms) or in a balm made from the shavings of the skin of the root of the Sombolo bush (against chigger fleas); the Mogombo plant is used to heal snakebites. We were shown Ngemba, a root garlic, and a herbal viagra that I wish I could identify let alone remember the name of.

She chopped a liana and drank thirstily. She grated the bark of one tree into ginger-like shavings, rolled a leaf into a cone and explained that you relieved earache by adding water and pouring the contents into your ear. She cut a length of the Kusa vine with deft and delicate touches of her machete. Within minutes she had removed the bark and between her palm and thigh woven the strands into a fibre. Each woven fibre is then woven into the nets, Bokia, they use for hunting. Her knowledge of the forest was encyclopedaeic, perhaps unsurprising as she was named after a tree in the forest.

Not all the uses of the plants are medicinal. If the pulp of a certain tree is smeared on the face of a woman it is meant to ensure that her husband will return from the hunt. I asked if there was anything they used to rub on their faces to keep their husbands away. Essandja shouted at me. I was alarmed, upset that I had transgressed and committed some faux pas with my facetious remark. Gesticulating wildly, Essandja pointed out that I was standing in a column of ants. She nimbly picked them off me. I smiled in thanks. She laughed, revealing her pointed teeth, a sign of beauty for the Ba’Aka, and shook her head playfully at my incompetence and lack of forest savvy.

The main forest pursuit of the BaAka is hunting. It is also the most eagerly awaited and anticipated activity and hence, as we set off on the hunt, there was a real sing-song atmosphere. With Bokia nets draped over their shoulders, everyone was upbeat and full of optimism. Walking down the old logging path the BaAka were shouting, full of banter and laughter. I waited with bated breath for one of them to break into song, “Hi ho Hi ho and off to work we go”, but refreshingly Disney has not yet infiltrated the jungles of equatorial Africa.

Suddenly the BaAka left the path and entered the forest, a tangle of roots, branches and lianas. But this did not deter the BaAka who moved quickly and nimbly though the forest, their diminutive stature no evolutionary quirk. Essandja turned around and uttered an onomatapeic “Twock, twock, twock” in imitation of my clumsy progress. She smiled and laughed. Her laughter was natural and infectious. I laughed at her joke, enjoying the camaraderie of the hunt. That was until my rucksack and I become ensnared by another vine. I cursed as Essandja slipped ahead of me into the jungle, never once getting her net caught in the vines and never looking down at her feet.

Collectively – the whole hunt is one of cooperation and togetherness involving men, women, children and on this occasion a young baby of six months – an area of forest was chosen in which to string up their nets. Using wooden hooks to attach them to trees, the nets were rapidly deployed in a large semi circle. There were some ten hunters in our party each carrying a net of some fifteen metres in length and a metre in width. Thus in total the semi-circle was approximately one hundred and fifty metres long and a metre high. Each hunter then checked that his or her net was strung out properly, cutting notches into trees in which to hang the net from, using vines and twigs to ensure that the net is firmly attached to the ground. The work was quick and thorough, their fingers wonderfully skilful. Little was left to chance, no gaps were left, no opportunity given to their quarry to escape. The trap was set.

Then the commotion began. The Ba’Aka began shouting and screaming. They pounded the undergrowth with branches, machetes and leaves to scare the animals out of hiding and drive them into the waiting nets. My heart raced in anticipation and expectation as they moved towards us, the noise building in a crescendo. And then there was silence. I looked around, bemused, trying to ascertain what and happened, what was going on. Had they caught something? But no, they had caught nothing. No success. The nets were dismantled, bundled onto shoulders and the hunters move on.

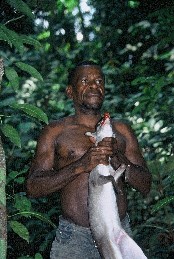

The process was repeated several times until we heard a bleat of distress. Ecstatic shrieking and childlike euphoria ensued as everyone rushed to the spot. “Mboloko. Mboloko”. A young blue duiker had been caught and was struggling vainly in the net. There was sheer terror in its eyes. Part of me recoiled from this, wanted to turn away but it is a natural process. They are not hunting for sport.

The duiker’s legs were broken in what to my sanitised western mind, conditioned by supermarkets and processed packages of meat, seemed like savage brutality. To the Ba’Aka it was a necessity – to lose the duiker at this stage would be a prodigal waste of time and energy. So as casually as one might snap a twig the hind legs of the small antelope were broken and it was dispatched with a heavy blow to the head. Again not a very comfortable sight for a westerner to watch, but this is the way they live; this was an authentic pygmy hunting experience.

I was a little cynical when we decided to go hunting with the pygmies. Wary of the fact that many ‘experiences’ with indigenous peoples are often mediated for public consumption, mediated for the west. I was worried that this was going to be a commercialised, touristy experience. It wasn’t. It was remarkably genuine, quite disturbing, but very, very memorable.

A second duiker was caught. The hunt had been successful and it was time to divide the spoils according to the rules of the group. The hunter whose net the animal is caught in gets the head and foreleg. The next person on the scene gets the other foreleg and so on. The division of the spoils occurred without discussion. Marantacae leaves were spread out on the ground and the two animals were laid out on them. The butchery began without fuss. They worked swiftly and nothing was wasted, even the blood was shared out – it is used in cooking. The leaves are folded together and bound with twine, each hunter departs with a neat package for the pot. The whole process of butchery takes place in a matter of minutes with little trace remaining of the bloody process. Literally nothing is wasted.

It is difficult to know how to describe and sum up my feelings of the whole hunt and my short glimpse into the world of the Ba’Aka. They are childlike, their laughter and playful banter is endearing and captivating. Yet to describe them as such would be to pigeon hole the experience and oversimplify the complexities of life that the Ba’Aka face.

Such difficulties are multitude, as I realised when we visited a Ba’Aka village the following day. I felt that we had overstepped that thin line between cultural tourism and cultural voyeurism. The previous day had been full of camaraderie, the shared thrill of the hunt. The Ba’Aka were full of laughter and we were sharing, in some small way, in their knowledge of the forest. Today’s visit to their village was a very different experience – the Ba’Aka seemed sullen and deflated in comparison. In the forest they were in their element, in their village they were subjugated and downtrodden. We handed over the obligatory gifts of salt, cigarettes and matches and beat a hasty retreat.

The forest home of the Ba’Aka will almost certainly not be the

same. With one foot in the traditional world they are easy prey and easily

taken advantage of. Yet it is not for me or others to tell the Ba’Aka

what to do or to try and protect them from the unscrupulous. Treated

as virtual slaves for much of their recent history, for once the Ba’Aka

should be allowed a say in their future rather than their future being

decided by others.

|

|

|