Chapter 11 - The End is Nigh

We awoke to bright sunshine that caused the severe overnight frost to sparkle and twinkle with a brilliance. The plains before us shimmered magically in the early morning light. The view was inspiring and imposing, even more so than last night, because of the heavy silence of morning. A silence that was deafening in its intensity.

The sunshine was not interrupted by the caprice of wind or weather, and the morning continued in all its glory. Basking in the early morning light, without the wind whipping and lashing as it had done so for the last few days, we were able to enjoy the peace and silence as we broke camp and cycled on to the top of the pass. The scenery seemed more inviting than yesterday, less hostile. The warmth of mossy greens and browns was reminiscent of Glencoe in Scotland, the land soft and welcoming. It was a land of plenty, of high pasture and good grazing.

As we reached the summit of the pass some ten kilometres from where we had camped the scenery changed slightly, but continued to impress. Across a steep valley we were confronted by a formidable ridge of peaks, their jagged edges contrasting starkly with the bright blue sky beyond. These dramatic mountains challenged not only the skyline but also the human spirit. We both felt the desire to, the desire to pit muscle against mountain. The freedom and the lightness of spirit that the space of the plains had created within us was replaced by the challenge of the heights in front of us The caps of snow were tantalising and alluring in the sharp sunshine.

The road then dropped away in a blur of passing tarmac, leaving the plains and mountains to memory, and instead exciting emotions of the present. A marker a few metres below the top read 4,572 metres, which explained the clarity and sharpness of images and the indelible stamp that they had left on my mind. With a whirring of rubber on tarmac we swiftly descended some thirty kilometres, losing altitude, gaining warmth, briefly pausing for some food in a small backwater of a village.

As we sped towards a bridge we saw a man gesticulating furiously at us to stop, to sign some papers or a register. Another brush with bureaucracy. What should we do? Stop and risk being thrown out of Tibet? With the greatest sense of calm, we did nothing. We turned a blind eye, emulating one of my heroes, Horatio Nelson, and sped past. Nervous glances behind revealed that the bypassed official was staring long and hard at us, no doubt his thoughts not too benign to foreigners or cyclists. Haunted by fears of recrimination, the incessant doubts of being a fugitive on the run, we saw each vehicle with a sense of foreboding. We were filled with dread that inside each car was an official who was about to bring our journey to a premature end.

The road climbed back up to 3,465 metres and then dropped into the Mekong valley. The valley was red and arid, devoid of life apart from the odd hamlet. The houses were of mud-brick lacking the luxury of whitewash, bland, without the usual blaze of colour around the windows, beams and rafters. This lack of colour, lack of warmth, was indicative of the harshness of life in the valley, revealing the poor quality of the soil. The valley and its mountains were only of use to the academic, the geologist and the geographer, bringing little joy to its inhabitants.

We had always said to ourselves that if for some reason we could not reach the source then at least Qamdo should be feasible, the next best thing, a realistic target. But if Qamdo was to be our consolation prize, then a poor consolation prize it was. The twenty kilometres preceding Qamdo were depressing in its industry, its litter, its greyness, stench and lack of life. The atmosphere was weary and negative and did not augur well for Qamdo itself. And yet such a foretaste did not disappoint, it was a fair reflection of the drab ordinariness of Qamdo.

Stomachs dictated food and, given the dreariness of the city, we opted for a ‘posh’ glass-fronted restaurant that would give us a last good meal before the final push to the source, still several hundred kilometres away. Our intention had been to eat, to stock up on provisions and quietly depart, not wishing to arouse too much suspicion, preferring to be inconspicuous and camp out of town. But our plans were to be thwarted, and our meal not the last good meal that we were to have, but the last meal of condemned men.

It all happened so quickly. It was over in an instant, faces no longer recognisable, passports no longer with us. It was all too quick for us to be stunned or shocked, we were merely left to contemplate what might have been, and yet, what still might be. We had been distracted. I was in the midst of ordering us a sumptuous feast; two particularly persistent and pushy monks were besieging Ian.

“Hello I am in charge of the affairs of foreigners.”

No flamboyant entry, no formal announcement, a quiet, almost unassuming introduction that was hardly noticed by Ian and I. Perhaps a subconscious wish by us to suppress the awful reality of the moment that was to come.

“Where are you from?”

“England,” Ian replied, a grudging reply, yet said almost inaudibly, not wishing to give too much away at this early stage.

“May I see your passports and papers, please.”

A rummaging through bags, a shuffling silence and two grubby passports were reluctantly handed over. A cursory glance at our passports revealed what the official had suspected, that we lacked the necessary and relevant documentation.

“Have you any other papers?” he asked out of politeness.

Papers. Papers. I knew full well what he was referring to, our authorisation, permission to travel in Tibet, but my mind, as was Ian’s, was full of evasive, facetious remarks. Ian thinking along the line of newspapers, me of rizlas.

“No,” was our empty reply.

A pause, a collection of thoughts, then, unphased, the official continued, “Have your meal. Then, please, will you come to the Foreign Affairs Office.” He proceeded to give us directions and then departed as unceremoniously as he had arrived, unfortunately with our passports.

We stared blankly at each other and waited for our meal to arrive. Slowly our minds caught up with events and what was happening, questions began racing in our minds and between each other. How had he known that we were here? They got here so quickly - they must have been tipped off? Was he playing ‘good cop’ and at the station would we meet ‘bad cop’? What should our cover story be? Do we play dumb? They will probably fine us and put us on a bus out of Tibet, but anything else? Maybe they will simply let us off with a stern reprimand? In the end, after some serious discussion, but much joking about this being the last meal of two condemned men, and talk of ‘Free the Qamdo Two’, we resolved to tell the truth, after all honesty is the best policy. We were going to say that we were following the Mekong having entered Tibet from Yunnan. But we were going to tell one lie: that we had airline tickets waiting for us in Lhasa hence it was imperative that we be allowed to continue to Lhasa - perhaps a bit optimistic.

Whilst we were still finishing off our meal and putting the finishing touches to our story, a young, clean-cut man entered. He was surprisingly well-dressed in a grey flannel suit. He smiled broadly, obviously a keen understudy, and nervously asked us to come with him.

Amused that our case had warranted the seriousness of an escort, we promised him that we would be with him shortly, meanwhile making a last minute statement to our video camera in defence of our actions. Uncertain of the outcome, our fate, we knew that we still had a chance of reaching the source, and could at least see the amusing side of our predicament.

Our escort guided us to the station on a motorbike aptly called ‘Wolf’ - it looked powerful and streetwise with leather tassels draped from the handlebars, a mean machine, but in reality was only 125 cc. A sheep in wolf's clothing. The station had the air and decor of an establishment bored by bureaucracy. Tired and neglected, the walls lacked a lick of paint. The corridors were empty, apart from the dust slowly collecting in the corners. The building was hollow, a shell, devoid of industry and far removed from hard work.

We were ushered into a bare, functional room where the Foreign Affairs official was seated behind a desk. He rose, politely gesticulating and asking us to sit down. He was a young forty-year old. He wore smart black-rimmed glasses, not heavy rimmed, as is the Chinese wont. his uniform was neat, his appearance unusually smart for a Chinese official. His eyes were bright and questioning, his face pleasant, his English surprisingly good - the first that we had heard in weeks. I could not help thinking that this would be as painful for him as it would be for us.

The politeness and desire to delay the inevitable continued with an offer of tea. The wait for tea led to an embarrassed silence as Ian and I sat like two naughty schoolboys in front of a headmaster torn by duty and emotion. Little heads peeped inquisitively around the doorway, and Ian remarked dryly that not even in a police station were we safe from onlookers, the ubiquitous staring brigade.

Tea arrived and the matters at hand could be stalled no longer. The official reluctantly began to read us the riot act, “According to the law of The People’s Republic of China, entry into Tibet was forbidden to foreigners travelling alone,” knowing full well that we ourselves knew that our actions were illegal. His speech came to a conclusion, “...and the punishment for unlawful entry, for not obeying the government, is a fine. Five hundred yuan (approximately £45).”

“And what after that?” I asked, wishing to know the full scale of our sentence as quickly as possible.

“You will be put on a bus.”

“ To where?”

“Chengdu.”

“When?”

A pause. Consultation. “Wednesday morning.”

“

Excellent a couple of nights on the beers,” was my facile reply,

an attempt to break the ice.

“Do we have to go all the way to Chengdu?” I challenged, looking for a way out.

“Yes.”

“Dege?” I suggested in the knowledge that Dege was just inside the Sichuan border, an open province, and from there we could launch a second attack on the source from a different approach.

More referral, then, “Yes, you can go to Dege.”

“What about Lhasa?” probed Ian.

“Lhasa is in Tibet. You do not have permission to travel in Tibet,” was the standard, obvious reply.

“But we have tickets waiting for us in Lhasa. We must get to Lhasa. From there we fly back to England,” persisted Ian.

“You must go to Chengdu. From there you can get a pass and fly to Lhasa.”

“But we have been travelling for many months and do not have much money. We cannot afford to fly from Chengdu,” Ian retaliated.

“You must go to Chengdu if you want to go to Lhasa,” was the official's final, emphatic reply.

We realised that the game was up and there was little that we could do but acquiesce. Our situation could have been worse and after all Dege was not necessarily the end of the line for us. Our conversation turned to formalities, of where we could stay, of what we could do tomorrow, of how we could get our bus tickets. ‘Wolf’, the slick easyrider would meet us tomorrow at 9.30 am to help us buy our tickets (a euphemism for ‘to make sure that we get the bus tickets and get out of town’), accommodation was organised, we could not leave Qamdo and unsurprisingly no photography was allowed.

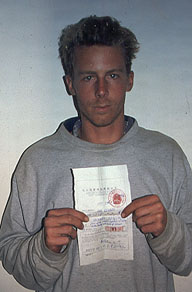

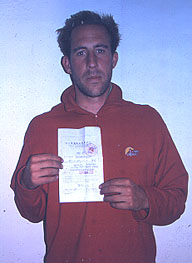

Still wishing to make this bitter pill more palatable to swallow, the whole proceedings as pleasant as possible, the official innocuously enquired, “Is Ireland beautiful?” We then descended into amiable, meaningless chit-chat about the respective merits of China and Ireland. Given the severity of our situation, I found such civil conversation to be surreal, especially as I had not been to Ireland and was not qualified to talk of its beauty. This harmless conversation was interrupted by the arrival of our hastily written fines. They were thin pieces of paper, one of which declared that I, “Justin Charles” was the “violator” on account of “unlawful traveling” (sic) according to “Law of the people’s republic of China on the Entry and exit of Aliens” - where is Agent Mulder when you need him most? And that this was “Adjudication on Entry and Exit Administration.”

The whole experience was relatively painless, and looking at the right hand corner of my fine I could see why. My number was “99004”, Ian’s was “99005”, the fourth and fifth offenders this year. One “violator” a month is an easy number to cope with, hence why the official could afford to be so good humoured about it all. It also explained why the station had such a redundant feel to it and how they had spotted us so easily.

We politely bade farewell and were escorted to our hotel. Never has a hotel check-in been so straightforward, totally hassle-free. I can heartily recommend the services of the Qamdo Public Security Bureau as to check-ins. What is more I took great puerile pleasure in filling in the registration form. When asked the reason for our stay, I wrote ‘Police Detention’; when asked ‘Received by’, I wrote ‘Police’.

I found the confines of our hotel room to be claustrophobic after the openness and freedom of camping. It was then, I suppose that the reality of the situation dawned upon us. At first there was just a dumb silence, then we sought consolation in beer. It was annoying that our main approach to the source had been closed to us. We felt frustrated that this had been a hurdle and yet we had fallen, and fallen hard. Hindsight preyed on our minds and how we could have and might have done things differently. The fatigue of being on the road caught up with and overwhelmed us, made us even wearier. Doubts and suspicions of not reaching the source began to plague the shadows of our minds. Negative thoughts, thoughts of failure were contemplated in all seriousness.

Our thoughts were confused but at no stage did we think that it was all over. There was still a chance to succeed, even if it was as distant and remote as the source itself. We still had the opportunity to silence all the ‘Doubting Thomas’s’ back home. As a result our determination and resolve strengthened and we began trying to map out our alternative route via Northern Sichuan into Qinghai (equally if not more out of bounds to independent foreign travellers than Tibet) and from there west to the source.

*

Drowsy with sleep it took me a while to reconcile myself to the strangeness of my surroundings. It was some time before I was able to come to terms with the soft warmth of the sheets, to appreciate the airiness of the room rather than the stale fusty atmosphere of our tent. As I awoke, I slowly began to realise that I did not have an appointment with an unforgiving saddle, but that ‘Wolf’ would be waiting downstairs for us. The comforts of the room were welcome, especially to an aching body, but the hardships of a tent floor would have been more welcome, particularly to a determined mind. The comforts of the room reminded me all too quickly that our quest for the source had been put on hold, for the time being.

‘Wolf’ was not downstairs waiting for us, he was knocking on the door and bursting into the room in his eagerness to assist. He seemed unphased by our lack of dress, let alone our state of readiness. Wolf was keen and smiling, probably as we were the cause of work, excitement, something to fill his otherwise mundane day. He rushed us down to the bus station and efficiently oversaw that we purchased two tickets to Dege. Once satisfied and believing that we were not going to abscond, he handed back our passports and departed, still smiling. We were free. Or were we?

“I feel as though I am under house arrest,” complained Ian.

“I know what you mean. Everyone seems to have heard about us. Everyone knows who we are. They all seem to know that we have been reprimanded by the PSB and are about to be escorted out of town.”

The furtive glances and knowing looks that were cast in our direction only confirmed that all and sundry knew of our criminal status. We were being watched not by a man in a tan raincoat, not by a plainclothes agent conspicuous in his attempts to blend in and look normal, but by the whole damned town. There was little option but to ‘hole out’ somewhere and try to pass the day in relative obscurity. I chose a small unremarkable wooden restaurant, with its concrete floor covered in bones, small wooden stools and tables.

I spent the day quietly in the corner minding my own business, reading and writing. I answered the inevitable questions of where I was from etc. and talked playfully with the children whose curiosity in me was unashamed. Their incredulous reaction to my presence was one of the few things of note that marked the passing of the day. Their spontaneous, wide-eyed, open-mouthed utterance of laowei revealed that the number 99004 on the top of my fine had probably been correct. Namely that very few foreigners had passed through here before. Another amusing point of note was the Tibetans describing me in Tibetan as injee lungpa, English. To me it sounded like something out of Willie Wonka’s Chocolate Factory rather than as a description of nationality. The other, more disquieting, aspect that I noticed was the Han Chinese treatment of the Tibetans. At best it was patronising and superior, at worst degrading and downright rude. The attitude of the Han did little to endear Qamdo to me, further marring my impression of this bleak, grim place.

Sadly this treatment of the Tibetans is not specific to Qamdo. Throughout much of Eastern Tibet, of what was once Amdo, the Chinese government is spending vast amounts of time and manpower on building and improving roads. To cope with road-building on such a scale there has been a vast influx of Muslims into the area, especially into Qinghai province. It is thought by some that in the not too distant future Muslims will outnumber Tibetans in the region. If that is not unsettling enough for the Tibetans, especially the nomads, the building of roads eats into their traditional grazing lands. But perhaps more worrying is the fact that roads provide access and open up Tibet to future exploitation by government and individuals . There is a deliberate and systematic destruction of the nomadic way of life with the introduction of roads, fencing and crippling taxes. A cruelly harsh winter has done little to help the plight of the nomads, now an endangered species.

*

We got up at five in the morning to catch the bus to Sichuan and thus escape the jurisdiction of the Tibetan Foreign Affairs Department. It was cold and pitch black – probably the best light in which to see the non-existent charms and sights of Qamdo. It was good to be on the move again after a day of waiting, to regain some sense of purpose and direction. And yet it was disappointing not to be cycling, not to be progressing under our own steam. We had little option but to take the bus, but it felt like cheating. Thus on that cold dark morning awaiting the arrival of our bus we were both a little deflated. We were stoical but by no means positive.

When the bus eventually departed, it strained and struggled out of Qamdo with the click of prayer beads and the chanting of mantras as encouragement. As the bus laboured against the incline a striking and dramatic panorama began to reveal itself below. A serrated mass of distant peaks, snow-capped mountains on the far horizon, a wondrous fragile relief map. The whole day’s journey was a feast of geographical features, stunning scenery and staggering vistas.

Sleep was not an option due to the lurching of the bus, the bitter cold and the clouds of cigarette smoke that choked the bus. Thus as the bus battled its way over a series of passes, all of which were over 4,300 metres, I was able content myself with the scenery. The views were mind-numbingly beautiful, which was a good thing, as it distracted from the road, which flirted dangerously with precipitous drops. The road, and I use the term loosely, was wild and rugged, ravaged by weather, distorted by landslides. But neither the condition of the road and nor the perils below seemed to phase the driver. He seemed oblivious and impervious to the vertiginous drops, as he careered around corners in carefree fashion, gambling that there would be no oncoming traffic on this single dirt track.

Space on the bus was at a premium and I only just managed to get half a seat, causing a loss of sensation in my right hand buttock. Later I managed to squeeze a seat out of the back row much to my folly - the bounce was so bad that I spent more time out of my seat rather than on it. The other passengers were mostly Han, the men smoking and spitting, the women silent and sullen. A group of soldiers tried to flex their muscle by making pathetic shooting motions at a majestic bird of prey soaring above the valley. But for me, a group of Tibetans, seven pilgrims going to Garze, were of much greater interest and far more pleasant. Their ululations as they reached the top of each pass were endearing. So too was the instinctive reaction of a woman to stick her tongue out at me, when she was thrown against me by the lurching of the bus. This showed that there was no ill will or bad feeling in her mouth toward me. Not only was there a quiet dignity in their manner, their bearing impressive, but they also had a warmth and friendliness. Many appreciative smiles and nods were happily exchanged between us and whenever the bus stopped for a meal Ian and I would rather congregate around them than the Han. They had a self-effacing charm.

Jomda was our overnight stop. There was little to the place other than as a stopover for buses and truck drivers. Drinking seemed the local preoccupation and we foolishly became embroiled with one of the bus drivers, thankfully not ours, in polishing off a couple of bottles of Baijiu. Baijiu literally translated means white spirit, which is not what it sounds but probably tastes little better. Saturated with alcohol we become the best of friends, addresses and telephone numbers (his is Qamdo 028 5812860) were exchanged and worryingly a late night drinking establishment was found.

There, Ian and I were encouraged to drink a bottle of Baijiu fortified with an unknown root at the bottom of the bottle. An experience not dissimilar to Mexican tequila and the worm. Mr Zhang told us that it had hallucinogenic properties. My Chinese, though aided by the inhibitions of alcohol, was not good enough to understand what he was saying, however his wobbly actions were pretty self-explanatory. We were sceptical but not wishing to give offence tried some of the proffered alcohol.

*

The revving of a bus engine was an ominous sign, especially as we were still in bed. It precipitated a mad rush to make the bus before it left. We did so only just in time, much to the delight of our fellow passengers, who were amused by our dishevelled state. The Baijiu might not have had hallucinogenic properties, but it certainly induced a heavy sleep and a heavy head the next morning . The fuzz in my brain (maybe Mr Zhang had implied that the root gives you a nasty headache rather than is hallucinogenic) was little brighter than the blizzard outside. It was thus a painful morning of self-inflicted hurt, of being jarred out of patchy sleep. A morning of having to suffer icy blasts through windows kept obstinately open as the bus continued to cough and splutter over passes where the snow was several feet deep in places. It was a painful day not only for me but also for my bike which suffered an injury: whilst tied to the top of the bus with a melee of luggage, pots, pans and boxes, the handlebars were damaged handlebars. It was damage that was more inconvenient and aesthetic than disruptive, but all the same unfortunate and frustrating.

In mid-afternoon, after snow-bound delays and hold ups on the road as trucks battled to pass each other, we arrived in Beima. Beima is in Sichuan and thus we were out of the jurisdiction of Tibet and free to leave the bus. We said a warm, but sad farewell to the Tibetans, for the bus continued south-west to Chengdu whilst we wanted to head north to Qinghai province and the source.

Beima was very much a one street town, a muddy one street town at that. Surrounded by rolling hills covered with a slight sprinkling of recent snow its setting was picturesque and peaceful, its inhabitants, largely Tibetans, curious but friendly, its children playful. The one muddy street and the horses loitering outside the houses bestowed a kind of Wild West atmosphere on the place, giving it an edge that I liked. The only thing that slightly marred my enjoyment of Beima was that several monks and women cautiously approached us, surreptitiously offering religious artefacts or worse still the dreaded hallucinogenic root from last night.

It was late afternoon but we wished to press on and were hopeful of still being able to get a lift north. Our intention was to get a lift to Yushu, or Jeykundo as the Tibetans called it, in Qinghai province and from their remount our bicycles and our assault on the source. Waiting patiently, we slowly began to realise that our chance of hitching a ride today were slim, rapidly dwindling to negligible. Searching for somewhere to bed down for the night, to my surprise, I overheard English being spoken in one of the huts. Intrigued, I pulled back the heavy blanket in the doorway and blinked into the darkness.

The room was dimly lit by a naked light bulb dependent on faltering electricity. The walls, covered with yellowing newspaper and faded posters, were propped up by worn but comfortable sofas. In the middle a fire stove with three blackened kettles was oozing warmth. The room had an earthy feel to it. This welcoming comfort was being enjoyed by a combination of Tibetans and Hui, all smiling and friendly, all captivated by the television in the corner. My initial shock at them watching an English programme (albeit it with Chinese subtitles) turned to horror when I discovered that it was Bruce Willis, worse still a VCD of ‘Die-hard’.

Most small towns, no matter how remote, seem to have at least one television, which is a focal point of a long cold Tibetan evening. Beima was no exception. But what surprised me more than anything was that they should have a VCD player and English language VCDs, even if they are all pirated discs. The widespread abundance over much of backward bucolic China of such technology is in stark contrast to the recent availability of VCDs in the UK.

My umbrage at the fact that these kindly unsuspecting people were being subjected to the violence and language of one of Hollywood's finest was sadly replaced by the fact that we had been deprived of any such form of entertainment, no matter how facile, for weeks. “Ian, Ian, guess what!” I shouted excitedly. An unknowing shake of the head. “They’ve got Die-hard on video!” An immediate beaming response and before we knew it we were both being welcomed by the assembled company and seated in front of the television.

If I found it strange to be watching the devastation generated by Bruce Willis, I wondered what the Tibetans were making of such American violence. I felt such devastation and violence to be all the more uncomfortable in the wake of the NATO bombing of the Chinese embassy in Kosovo. Throughout China we were frequently asked about the bombing and whether or not we were Americans. We were always eager to express the fact that we were British and that Britain is very different from America. There was some very stark footage in the Chinese media of the remains of the three journalists killed in the bombing being returned to China. Footage of a huge outpouring of grief, footage that gave rise, whether deliberately or not, to a passionate wave of nationalism and heartfelt anti-American feeling. It was easy to be cynical, to criticise such reporting as propaganda but I was sure that had the roles been reversed, the tabloid press back at home would have been no less forthright.

*

Early the next morning there was a knocking at our door. It was Denzeng. Denzeng, a young Tibetan in his late twenties wore shoulder length hair swept back, a denim jacket and prayer beads around his left wrist. He was laid-back and cool, with a handsome face and warm smile. He was Tibet’s equivalent of a rock star. He was also a truck driver who had agreed last night to give us a lift to Yushu.

As we set off, bikes and panniers safely stowed on top of the truck, the weather outside was bleak. It was snowing so hard that even the dzus and yaks were feeling the bitter cold and were congregating around the nomad’s tents for warmth, shelter and food. The cold whiteness of the plains outside was in contrast to the brightly coloured warmth of the cab, and I felt like a bit part in the old Yorkie advert. Remember it? Snowing heavily, truck driver, the goodness of Yorkie? I certainly could have done with a Yorkie bar at that time, not having had time for any sort of breakfast before our rushed departure. But my pangs of hunger and suffering were inconsequential in comparison to the freezing discomfort of the other passenger on the truck. Due to lack of space, he literally was on the truck, exposed to the freezing outside, a most unenviable position to be in. A muffled cry some forty kilometres out of Beima signalled his discomfort and that endurance had been pushed to its limits. The torment of temperature had become too much. It was a squeeze in the cab with four but infinitely preferable to having the poor man freeze to death because we selfishly wanted a little extra space.

There was hardly a quiet moment throughout the journey due to the dubious pleasure of Denzeng’s tape collection and his amiable chatter. Most of his tapes were Chinese and invariably played at the wrong speed. When too fast they sounded like the Chinese version of the Smurfs. I however preferred his Tibetan music, plaintive folk songs that had a lilting lyricism to them. But it was his light-hearted conversation and engaging smile that won the talent contest. He took an immediate liking to us, especially to Ian, though he was concerned that neither of us were married - he is twenty-seven and already has two kids, one of whom was twenty-seven days old.

By late morning the weather had abated and the sun, struggling to free itself from the enveloping clouds, was beginning to warm the expanse of plains surrounding us. We were back in the wilderness of big open country, vastness of space, ample grazing. The plains and valleys were flecked with black - the large rectangular tents of the nomads, called ‘ba’. These tents vary, but are generally rectangular and quite sizeable with two wooden posts supporting the inside, while the outside is held up by twelve posts and a spidery array of guy ropes, giving the impression of a circus ‘Big Top’. Prayer flags emblazon the guy ropes, acting as promotional banners. The tents are made from twelve-inch strips of loosely woven yak hair sewn together side by side that the women can be seen weaving outside their temporary homes. Made from yak hair they are lighter than the yurts of the nomads in Mongolia or the Tajiks in XinjiangThe surrounding plains are filled with grazing livestock, the frolicking of dzo calves, solitary horses and flocks of sheep.

The nomads travel in groups of families, the families pitching their tents at quite a distance from each other due to the poor quality of grazing. Traditionally, the men tend to the herds whilst the women and children stay near their tents carrying out daily chores. Though in our experience many of the men were off at town and the women were left to look after children, chores and the herds. Each family is guarded by a vicious mastiff that is the bane of any foreign cyclists. We, especially Ian, had a number of close shaves with these ferocious, wild-eyed dogs that scared the living daylights out of us - I am sure that the adage about the bite not being as bad as the bark does not apply to Tibetan dogs.

In the late afternoon we drove into Serxe positioned under snow capped mountains at one end of a long rolling valley. The surrounding beauty was the only positive attribute to the manufactured soulless conglomeration of tiles, blue glass and concrete. Serxe was very much a Chinese rather than Tibetan town and lacked the down to earth colour and character of Beima. The inhabitants of Serxe looked out of place in their local garb, displaced in the sterile streets. Given the drab surroundings, the Tibetans and particularly their dress stood out - thankfully they have retained a tradition in their dress that the town itself lacks. Natural dyes and colours predominated, deep reds and dull mauves, but it was the fashion the style of their clothes that caught my eye. The men wore heavy warm garments either with long sleeves that flapped comically below the hand or preferring the ‘off the shoulder look’, the right hand sleeve wrapped around the waist. The women wore equally heavy garments, usually of a duller darker shade than the men. Their headgear was of particular note, intriguing items of heavy cloth that would not look out of place on the set of ‘My Fair Lady’.

*

A light overnight snow lay sprinkled over the town and countryside, hiding much of the ugliness of Serxe, as Denzeng, accompanied by his young family, came to pick us up and take us on to Yushu a further 139 kilometres nearer the source. Roma, Denzeng’s wife, was young with a petite figure and pretty face. Her cheeks were rouged by the elements, her hair was thick and black, parted in the middle and tied in a plait at her back. She was shy. Her reticence seemed mainly towards us, due to her unfamiliarity with foreigners. She did not speak Chinese (Mandarin) and thus our conversation with her was limited to the monosyllabic.

Throughout the journey Roma talked excitedly and animatedly to Denzeng, who at times would appear to be not listening. Like husbands the world over he would wear a disinterested look when his wife was talking at him rather than to him. Yet despite Denzeng’s moments of vacancy, they were clearly a couple very much in love, happy with each others company and with their two adorable children. Bambam and Dindin were the children’s names, names that would not be out of place in Bedrock, but there the similarity with the Flintstones ended.

Bambam was an intelligent, inquisitive two-year-old who was obviously excited by the ride in Dad’s truck. Tiny hands clung to the dashboard, as his eager eyes were transfixed by the passing scenery. However Babam was clearly troubled by the fact that Ian and I were in the cab. We tried offering him biscuits as a peace token to try to show that we meant no harm, but our attempts were received with scepticism and did little to win us over. His stomach might have been tempted by the biscuits, but his heart and eyes were too afraid. He knew that our alien hands had tainted the biscuits and thus he would not accept any, even if offered them by his mother. Dindin , on the other hand, was oblivious to our presence. His month old body simply wanted sleep and that was exactly what he did. Tightly wrapped up in blankets that allowed no movement he had little option. Bound in this oblong bundle of blankets, only his tiny head to be seen, Dindin looked like a North American baby strapped to his mother’s back - for that matter Roma’s hairstyle was not unlike that of a squaw.

As the snow and wind blasted the landscape around us, I felt wonderful warmth in the cab, a homely joy and pleasure at being able to share the journey with Denzeng and his family. Ian also enjoyed this privilege, despite the discomfort of having the gearstick between his legs and having to put up with Denzeng changing gear in his crotch. By the end of the journey Ian would come to dread the sight of uphill or muddy, rutted sections of the road that would require the engaging of lower gears and thus pain. At times it was difficult to distinguish between the whining and groaning of the engine and that of the unfortunate Ian.

The bond of family that was so obvious made me think of home many miles distant and the future. It made me think of times that are perhaps equally distant but of thoughts of settling down and enjoying a family of my own. With Bambam fast asleep in my lap, and the comforting smell of baby and stale milk emanating from the bundle that was Dindin by my side, my mind was preoccupied with thoughts of potential fatherhood rather than deeds of exploration. But as Bambam was jarred awake, I was awoken from my reverie, for his eyes quickly filled with terror as he saw me cuddling him. He uttered sharp, breathless cries of horror as he scrambled away from me, seeking the soothing sanctuary of his mother.

As Bambam, scared and frightened, studied me with hurt reproachfulness from the corner of the cab, my paternal pretensions were put on hold and I returned to studying the snowy surrounds. My thoughts wandered aimlessly with the boredom of travel, of hours of relentless scenery, and my imagination was invoked as I carefully studied the horizon in the hope of a prize even more elusive than family. The prize of seeing a snow leopard. But given that the snow leopard is one of the rarest animals on the planet, in my heart of hearts I knew that this was just another romantic dream.

The road, as Denzeng had warned us was awful. At times it was little better than a quagmire and several times we had to stop and go to the aid of mud-bound trucks. I thought of how frustrating it must be to travel along this road on a weekly basis, reduced to little more than walking pace due to the appalling condition of the road surface. But then the life of the truck driver, even the commuter, is little better back at home, where travel is blighted by roadworks and the tension of traffic. Though the going may be slow here in Tibet at least there is none of the temper and rage that unfortunately pollutes our roads. Life in Tibet, most of South East Asia for that matter, is not confined and conditioned by the time constraints of the west. On returning home after five months away it is the stress and the rush to meet deadlines and appointments, the fear of being late or delayed, that clearly troubles most peoples everyday life, especially in the bustle of the cities.

As we approached the Qinghai-Sichuan border, doubt crept into our minds about whether we would be allowed to pass the border. Xining, the capital of Qinghai, is open to foreigners but many parts of Qinghai are not and it is often not easy to establish before arriving in the region what the current status quo is with regard to access. Denzeng instructed us not to say a word and to pretend that we unable to understand Chinese, to simply hand over our passports. I trusted him, yet was perhaps a little unsure of his confidence and felt a little uncomfortable being totally in his hands. As it was I need not have worried for he was true to his word and got us safely past the checkpoint and an official who looked as though he could have been awkward. The only thing that marred Denzeng’s performance was his disgruntlement at having to pay what looked like an arbitrary charge for his cargo, though it was only 10 yuan. Unknowing of our legality, whether we were again breaking the laws of the PRC, every official induced in us a mild sense of panic, and this official was no different. Perhaps our fugitive fear was unfounded because to most officials we were simply two foreigners, beyond their responsibility. This official’s lack of interest in us was one of the few times that I have been grateful for the Chinese concept of responsibility, for not caring if it does not concern them, not wishing to get involved unnecessarily.

A sigh of relief and exchange of happy smiles as we successfully entered Qinghai and several kilometres down the road we stopped for an impromptu celebratory meal in Xiwu. Then it was back on the road for the last stretch to Yushu, but not before seeing a monk peeing by the side of the road. This is not the first time that I have seen a monk squat and pee (obviously like the Scots and their kilts, the monks wear nothing under their robes), but was the most public and obvious case of toilet that I have come across. It is not the action of squatting and peeing that struck me, I have witnessed it in several other countries from Pakistan to Ethiopia, but the total lack of effort to be discreet and to seek privacy, that grated with my prim English reserve. If this is the behaviour of monks then there is little surprise at the conditions of many of the public facilities, the use of toilet in China in general.

Arrival in Yushu meant a sad goodbye to Denzeng. He reiterated to us several times that we did not need fear officialdom but rather should be careful of the road and the weather conditions, both of which he said would be at best unpleasant. I was sad to see Denzeng go, sad to lose his protective presence, his comforting confidence, but especially his warm-heartedness and his infectious smile. Yet at the same time after five days on the road, of not being on a bike, days spent on a frustrating enforced detour, it would be good to get going again under our own steam. It would be good to get back on track to the source, especially now that we were closer than ever.

*

Sunday morning was a bright sunny morning that brought an icy blast not from the weather but from Ian. At first I thought it was early morning moodiness, to which we are both susceptible, compounded by Manchester United’s emphatic 2-0 win over Newcastle United in the FA Cup - Ian had been supporting the underdog Newcastle. But Ian felt that he had a genuine grievance and was clearly upset about it, namely that I was trying to push us too hard, did not consider Ian’s position and tried continually to get my own way by urging for more. I wrote in my diary at the time. “Fair enough that I do try to push our daily mileage up, I am concerned that those that contributed to the trip and those that gave us sponsorship might think that we have had it too easy. But I think that it is a little harsh to say that I do not consider Ian's position; I try to as much as possible and would certainly not carry on if Ian was struggling or feeling unwell. Worryingly he quoted not one but several occasions when I had forced us on against his will - if so it was not my intention to make Ian uncomfortable or suffer, it was not a deliberate act, I must not have realised how much he was hurting.” Later in the day Ian apologised for his outburst, something that could not have been easy and I admire him for doing so. Not because he retracted anything that he had said earlier, that had been spontaneous, but because he had said sorry. That takes courage and too few people have that courage.

Minds spoken, it was good to be back on the road. Perhaps we were so preoccupied with thoughts of being back in the saddle that we inadvertently turned the wrong way out of town, a scenic detour that took us an hour and did little for our map-reading credibility. It would simply have been much easier to ask the locals for directions, though this is not always easy, their knowledge of the surrounding area being far from good. This is a bugbear of mine, the Chinese lack a sense of direction and any ability to read a map. With such great forebears as the explorer-admiral Zhong He one might have expected the Chinese to have an innate ability when it comes to orientation, but this is sadly not so.

The day was filled with both the pain and the pleasure of pedalling. The pleasure of achievement and progress, and of the wonderful reception and reaction of villagers and passing vehicles. We were stopped several times by vehicles curious as to our destination and impressed by our determination. Once a jeep full of monks stopped suddenly and piled out to poke and prod us in disbelief. The pain reared its ugly head in the form of a blistering headwind that slowed progress, blasted skin and blew up little dust devils that stung our faces and bare legs. By the end of the day our faces were raw, weather-beaten and tired.

By late afternoon we sought refuge in a small glacial valley off the main valley up which we had persevered all day long. We pitched tent about one hundred yards away from two small nomadic tents, belonging to four young children aged nine to three and two women, the men nowhere to be seen. The women and children were herding their dzu back to the tents for the night, shelter for the dzu provided by a two foot high wall within which they were tethered for the night, rope pegged to stakes. Nearby a large pile of dzu dung, surrounding which were the collected deposits from the previous day left out to dry before being piled up. A cheap and readily available fuel for fire and cooking, especially as there are no or very few trees on the Tibetan plains, and thus no alternative source of fuel.

*

I awoke to the sound of grunting and quickly established that it was not Ian but the dzu heading off to graze on higher ground. Crawling out of the tent I found that we were surrounded by dzu. The women were busy releasing the rest of the herd, some of whom plodded off to pasture, others frolicked and gambolled, enjoying their new-found freedom with a frenzied burst of energy. Once all the animals were released the women busied themselves with collecting all the dung, skilfully scooping it up with a pitchfork and depositing it in a basket on their back, all in one swift, fluid motion. Their morning business completed it was time for breakfast, probably of tsampa and yak butter, perhaps dried dzu meat. It was a scene of everyday routine on the high plains, but watching and witnessing even such basics of nomadic life in the middle of nowhere on a fine, crisp morning with blue skies, was infinitely preferable to waking up in the crowds of London and setting off to work surrounded by alien faces and confronted by delay and stress.

The day’s cycling was uneventful. The wind persisted, but fortunately not as savagely as yesterday when its strength had been intimidating. Passing vehicles, few and far between, continued to express their support, admiration and often incredulity. Again we were stopped by a couple of jeeps wanting to question us, to ask us where we were headed to, to check our sanity levels, to congratulate us and to shake our hands. The fact that we both wore shorts when we cycling caused as much consternation and fascination as the cycling itself. “Leng bu leng?” “Are you not cold?” was a frequently asked question and our interrogators were always surprised when we answer, “Bu Leng”, i.e. not cold. Not only our shorts, but our hairy legs were subject to much scrutiny: to women and children the hair on our legs caused horror and revulsion, to the men amusement. I was often tempted to go one step further and show them my hairy chest, but feared that this might seriously offend and cause all subsequent foreigners to be categorised on an equal footing with the Yeti.

“The vastness of the scenery reminds me of the sea.” An innocuous enough comment from Ian, I could see what he meant, but it got me thinking of cream teas by the seaside in England. Cream teas got me craving food, pangs of hunger, stomach grumbling, I could think of little else but gluttony. The seaside reminded me of England and I became preoccupied by thoughts of friends and family, of what various people were up to at this precise moment (hopefully sleeping, as it was three am on a Monday morning). I spent at least an hour daydreaming. It is strange the associations, the drifting of the mind that can be caused as the result of a single comment or pangs of hunger.

All day the road was dreadful, especially so for cyclists. Rutted and stony, it caused our front wheels to bounce uncontrollably, and required constant concentration. Frustration had irked all day long, but as soon as we stopped in the late afternoon sun to pitch camp, our moods changed. The hardship of the road was quickly forgotten, replaced by enjoyment of the uplifting sun and the scenery. Our mood swing was capricious, but the relief at the niggle of the day being over and finally being able to enjoy the scenery was definitely tangible.

We were camped by a shallow, crystal clear stream that gurgled playfully along the valley floor, as dzu filled the plain, their contented grunts of grazing filling the air. Marmots squeaking excitedly as they emerged from their holes, heads nervously scanning the horizon for danger. The valley was a wealth of soft hues, comforting browns and reassuring greens, natural and unspoilt. Snow-capped mountains, proud and erect, at one end of the valley, contrasted with the soft rolling hills of the other. All this space, this untouched beauty and we were able to enjoy it alone in the glorious sunshine. Moments like this perhaps more than compensated for the numbness, strain and tedium of cycling great distances.

Having performed our by now habitual evening chores of cooking, washing in the freezing water of streams, and of updating diaries, we were just settling down for the night when we were visited by the ‘Lone Ranger’ of the high plateau. More interested in our tent and equipment than herding his dzu up for the night, he noisily poked his head into the tent. His horse tried to follow suite. His horse, a grey, furthering the Lone Ranger metaphor, was ostentatiously dressed in red pom-poms, a measure of the man’s status. The ‘Lone Ranger’ himself was a real character, with thick heavy rimmed glasses as per Jiang Zemin that were incongruous with the outdoor cowboy image. He wore a faded denim jacket, battered hat and black shoes that were more suitable to an office than the Tibetan plateau. A gleaming gold tooth straight out of a Serge Leone spaghetti western was his pièce de resistance. He was actually quite concerned for our welfare, not believing that we would be warm enough. His concern was touching, his invitation to come over and bed down at his ranch, nomadic tent, generous. Flattered by his invitation we politely declined. He shook his head and still smiling galloped off into the distance.

*

The skies looked ominous as I peered cautiously out of the tent the next morning. It was going to be one of those days of few pleasures, a day testing of temperament and temper, a day when we would have to knuckle down and get on with the task at hand no matter how grim. In light of this, and in the expectation that we could hopefully get some food twenty kilometres further down the road (our first meal not cooked by ourselves since leaving Yushu over two days ago), we decided to break camp only having had a packet of biscuits between us.

Having climbed a small pass of 4,323 metres - I can hardly believe that I have just described such a pass as small, but it is all relative, and in comparison to some of the arduous assents that we were faced with, this was small - we began racing downhill when disaster struck. The relentless, unforgiving road surface won its wore of attrition with my front rack as, despite my efforts to the contrary, my rack finally succumbed to wear and tear. The rack sheared, snapping off into my wheel, breaking two spokes, and forcing me to come to a sudden stop. Firstly I was lucky not to have been sent flying over the handlebars, secondly that only two spokes had been broken as we only had two spares for the front wheel. As I set about dismantling what remained of my mangled rack and replacing the two spokes, Ian began making porridge for breakfast - what more could a man want when calamity befalls than a bowl of steaming porridge to settle the stomach. Much to the fascination of a father and son, who lived in a nearby hut and who had come across to watch these strange goings-on, the wheel was duly repaired. I presented the remains of the rack presented to the delighted little boy as a do-it-yourself Meccano set, we had our fill of porridge and were back on the road.

At first it was strange cycling without the front rack. Not only because of the shift in weight due to my two front panniers being strapped on to my already heavily laden back rack, but also due to the fact the comparative silence when cycling. Gone was the annoying squeaking of my front rack labouring under the strain. My uneasiness at the weight distribution faded as I learned to compensate and as the scenery grabbed my thoughts. It was not unlike the Welsh mountains, but more dramatic, on a bigger scale with pinnacles of rock jutting proudly forth, jagged edges tearing at the sky, bestowing an almost Tolkeinesque feel to the landscape.

What followed was an unpleasant few hours best described by a diary extract. “And then the rain came. Hard, driving, biting at exposed parts of the face, saturating waterproofs. My feet were sodden, toes squelching unpleasantly in soaking socks. The wet was uncomfortable, made us feel miserable and sapped our energy, but what disheartened me most was the fact that with my anorak done tightly up my vision was limited, almost non-existent. There is little more disconcerting than being able to see a couple of feet ahead in driving rain, staring at muddy road, puddles, muddy road, puddles. The going under tyre was soft and heavy, progress laboriously slow. The wind chilled, I was racked with shivers of damp, and my hands were painfully numb. But still it was the fact that all I could see was the mud at my feet was what I found to be most dispiriting.”

But as with yesterday, our moods changed with a slight easing of the rain and a break in the weather. A ray of sunshine forcing its way through the foreboding cloud gave us hope that this would be the end of such unpleasantness. With tent pitched, bikes and bodies cleansed of accumulated mud and general road filth, the hardship of frozen fingers was forgotten. It is surprising how much our moods were affected by the weather. Back at home, the vagaries of weather have an effect on daily lives and our state of mind, but only in a small way. Exposed on the Tibetan plateau, the elements were much more powerful and fearsome, consequently we were that much more susceptible and vulnerable to its whims.

*

The next morning the rain was back and its depressing patter on the tent, however light, dampened spirits and mind. Even the usually restorative powers of porridge did little to alleviate the morning gloom. The BBC news on Ian’s short-wave radio equally failed to cheer us up. It was an effort to rouse ourselves and face the unpleasant elements, but once outside and on the road our moods improved, for today we would hopefully make it to Zadoi. Zadoi was the last town of any note or size on the Mekong (Zaqen and Mugxung (Moyun) were the only other names of concern to the cartographer, but both were much smaller being only settlements). Few foreigners had made it to Zadoi, clearance from the police bring one of the many difficulties of accessing the region. For us it had been a definite goal from the outset and to reach it quite an accomplishment.

The scenery, as ever, further brightened our spirits. In the early morning we cycled through a dramatic gorge of exhilarating beauty that put the West Country’s Cheddar Gorge to shame. Thankfully there was none of the accompanying paraphernalia of tourism. No tea houses or ice cream vans touting for business from those out on a Sunday afternoon drive. Coming out of the gorge we crossed the Atlantic and much of the American continent, figuratively speaking, to the rugged outdoors reminiscent of the Rockies. Craggy mountains, steep slopes covered in conifers, a wilderness feel, all with the backdrop of a bright blue sky. Then, suddenly, around the next corner we had re-crossed the Atlantic and were back in Europe, to the Alps and softer slopes, more pleasing to the eye, gracious and shallow, a mellow alpine atmosphere abounded.

We were also reunited with the Mekong. It was comforting to be back in visual contact with this old friend, but I was a little disconcerted by its size, by the width of the river. We were supposed to be nearing the source and to my mind that meant that the river should be getting smaller. Yet here the Mekong was at least twenty to thirty metres wide. As wide as we had seen it last, several hundred kilometres back in Qamdo, though admittedly it was shallower. The volume of water might not have been as great, but nevertheless The Mekong was already an impressive river at this early stage in its life. I was troubled, worried that for some inexplicable reason the distance to the source on the maps had been foreshortened and that in reality we had much further to go.

In the early afternoon we arrived in Zadoi, Ian summing up the disappointment that we both felt: “We have travelled four thousand kilometres in search of the source to see this?”

Zadoi is a town of little consequence. In the 1950s, as Michel Peissel explains in his book ‘The Last Barbarians’, it was used by the PLA as a garrison in the six year War of Kanting against the Khampas. But today, its one street flanked by characterless concrete buildings, Zadoi will certainly not be winning any prizes for its architecture, any atmosphere and character having long since departed. But if Zadoi was not much to look at we at least hoped that it would be a source of information about the possibility of travel further along the Mekong, and the state of the road to Zaqen and Mugxung. The news that we heard was not too our liking in that neither road was suitable for bicycles, especially the road to Mugxung. But this would not deter us.

*

Zadoi was sad to see us go. At least the smiling couple who ran the Spartan guesthouse where we spent the night were. So too the couple who ran the tiny restaurant where we had had baozi (dumplings) for breakfast. They gave us friendly words of advice, stressed time and time again that we should take care. Did they know something that we did not? Did they somehow know what lay in store for us today?

They had warned us about the state of the road, obviously using the word road in its loosest possible sense, but little could have prepared us for what we had to endure. The road pitched and rolled with a tempestuous fury that would make the most hardened travellers seasick, that would hurl the inexperienced or unsuspecting overboard and down the precipitous slope with disdain. Negotiating such treacherous and turbulent terrain was gruelling, with progress being painstakingly slow. As the road veered away from the Mekong the going turned from bad to worse. The Chinese Road Authorities had evidently thought it economical and amusing to take a short cut to Zaqen - that this involved two weary cyclists having to force themselves up yet another daunting pass was obviously of no consequence to them.

The height of the pass was a difficult enough struggle, the altitude causing a shortness of breath that was alarming. The steep gradient did little to relieve our laboured breathing. But to make matters worse, no downright antisocial, the road surface was loose, giving our weary tyres no purchase. This caused us to slip, stumble and stagger, making little or no headway. Having no front rack, all the weight of my panniers was on the rear of the bike causing the front wheel to bounce on the uneven ground, rearing up uncontrollably. At times I felt as though I was riding a wild untamed horse and several times I was thrown off. Ousted from my saddle, I had to suffer the indignity of walking. Pushing a heavily laden bicycle when the going underfoot is uncertain, often slipping and losing footing or bicycle, usually both, on a hot day, at a height of more than 4,500 metres was by no means an easy task. There was much sweating, much cursing and much shortness of breath caused by such exertion at altitude.

“Never again,” muttered Ian to himself as we reached the top, collapsing to the ground only able to exchange wry looks. The spectacular views from the summit of the pass just compensated for such hardship. It was only once I had regained my breath and my pulse rate had returned to something like normality that I could begin to appreciate the stunning series of mountains that lay stretched out below and all around us. It was quite simply breathtaking, perhaps not what I needed at that precise moment in time given my struggle for breath over the last hour or so of uphill toil. It was awe inspiring that the terrain could be so savage, an unrelenting mass of jagged mountains jousting for position and prominence. The beauty of the view was that it was undaunted, unbroken, unchallenged, a raw roughness.

The descent back down to the Mekong was no less unyielding, no less rough than the dramatic scenery. Conventional bicycle wheels, ordinary rims, would not have been able to survive the battering that the road had in store for us. Fortunately we had Mavic rims and wheels reinforced by Psycho Bike Shop in Battersea - at the time I had thought it perhaps an unnecessary expenditure but now more than appreciated the extra workmanship. An oft repeated and painfully obvious message, but it is invariably best to heed, 'better safe than sorry'.

Back at river level I was grateful that the bumping and bruising of the descent had come to an end and to be alongside the river. I was also reassured to see that the width of the river was now a more manageable size, i.e. conformed to my very non-geographical image of a river less than a hundred kilometres from its source. Source, source, dare I mention the word because by the sound of the disgruntled rumblings above, the heavens were clearly in dispute about whether or not to grant us access. The skies were dangerously dark, heavy and full of malicious intent. The thunderous noise was belittling. We felt very small and inconsequential.

“What have we done to so upset the Gods? Do we need permission to reach the source?” I asked Ian.

“They are drafting a series of tests for us. We have to overcome these before we are allowed to proceed.”

Ian was not far from the truth, for it did sound as if the tumultuous conflagration above was evidence that our fate was held in the balance. Distant cackles in the background seemed to mock us. The rumble of thunder was the riotous applause for a particularly ingenious deterrent. Thunderclaps were a belligerent God banging on the table to get a point across. However it soon became clear that we had done something wrong to incur the wrath of the Gods and incite their displeasure, for they began to vent their anger with a vengeance. We were subjected to not rain, not wind, not sleet, not snow, but hailstones.

These were not just ordinary hailstones, but sizeable, potentially harmful missiles. The Chinese call hail bing pao, literally ice balls, an onomatopoeic word reminiscent of the sound that they make on contact with the ground and also of table tennis balls, whose size these overgrown hailstones more than matched. The first hailstone landed to my right, alone, astray, like a miss-hit golf shot but there were no warnings of ‘fore’.

“Ian, Ian, come and look at this,” I jabbered like an excited child.

We were both so incredulous at its size, its sudden unannounced arrival that we did not contemplate the obvious, that there would be more. We were quickly aroused from our daze as all about us the ground began to ping with their arrival. A nearby stream was churning under this heavenly barrage, its water seemingly raked by automatic gunfire, a gunfire of such intensity that would rival the waters of Normandy as shown in Steven Spielberg’s ‘Saving Private Ryan’.

The size and concentration of these hailstones was fascinating and gave me a unique bizarre thrill, the childlike excitement of first hand experience of an awesome display. But suddenly all fascination was stung out of me as I was hit square and hard in the back, as if hit by a squash ball.

“Those rocks over there,” yelled Ian as he sensibly headed for cover.

The adrenaline rush turned to fear and a feeling of self-preservation overwhelmed us as we both scurried helplessly for shelter, and yet I shouted after Ian. “The video. Get the video out.” Despite the feeling of vulnerability, that we were exposed to the elements and being hit with frightening regularity, I wanted to try to capture some of this ferocity on film. Why at such a critical moment was I thinking of filming?

The rocks proved little protection and we ended up cowering behind our bicycles, fearful, yet in awe of this savage display of the force of nature. Again that feeling of insignificance, of a little boy floundering out of his depth.

Thankfully the storm was short-lived and as it died away we chattered in animated fashion, eyes wide with relief, wild with excitement, overtaken by a boyish enthusiasm and pumped up with adrenaline having just witnessed natural elements at their most brutal. We were thrilled. But this was not all that the Gods had in store for us; we still had a couple of tests to pass, more obstacles to overcome. Next was an icy cold stream, too deep and wide to cycle through that had to be traversed barefooted and barelegged. Then, trousers and boots back on, we had to struggle through plains of mud. The mud clung our wheels, rendering cycling impossible and leaving clothes and bikes covered in this cloying mud. As if that was not enough, the rain turned back to hail and we had to make a mad dash for the relative safety of Zaqen.

After such an ordeal, such an eventful journey, I expected Zaqen to be warm and welcoming, a source of comfort and solace to weary travellers. It was not. The town, if such a dilapidated run-down collection of houses can qualify as such, was eerily quiet and deserted. As the rain continued to fall a couple of mangy dogs loitered and skulked in the wet. I felt the town to be possessed with a surreal air, the silence to be strange, unsettling. The emptiness made me feel as though I was being observed from behind closed curtains, a curious mix between the X Files and Asterix and the Soothsayer (a strange combination in itself that might reveal how unnerved I was by the whole experience).

“It’s like a deserted Wild West town. Where is everybody?” said Ian as we tentatively tried to seek out a human face, knocking on silent doors. “I saw a woman over there by that door,” but the woman that Ian saw, or imagined that he saw, was no longer there. It was weird.

“Ian, look at this,” I shouted across to Ian from a bare room, holding an ancient Lee Enfield rifle that I had found in the corner. Ian’s face paled as he motioned behind me. The owner of the rifle appeared from out of a doorway behind me - an awkward, embarrassing moment that is difficult enough to explain at the best of times, nigh on impossible in Zaqen where their annual quota of foreigners rarely rises above zero. The unfortunate man’s shock at such a sight must have matched my embarrassment. He was a shy young man with a helpful face, yet despite his face he did little to help us other than take us to see Anju.

Anju, sporting his green ‘Qinghai’ jacket with obvious pride, was the man in the know, Mr Zaqen, full of local information and helpful advice. In spite of the fact that Zaqen seemed to have a population of approximately eight, most of whom where Anju's family, and that the village had no store, no shops, was a ragged assembly of derelict houses, Anju took his role seriously. Diminutive in stature, he was certainly not lacking in heart or in his eagerness to please. He sat us down on wooden stools and began reeling off names, places and possibilities, information about the source and proceeding on from here. The general gist of his words of wisdom was that he was unable to provide horses for us and that we should return to Zadoi and from there proceed to Mugxung and then on to the source. Not the best of news to two weary cyclists who had just done battle with the elements and come off worse for wear.

Anju sensed our frustration and disappointment at such news and asked his wife to cook some noodles for us. Even now months after our return I still can taste such noodles and crave them - thick and doughy with chewy bits of beef. However it was the broth that I liked most, a vinegary, savoury delight that was exceptionally moorish. Duly fed, Anju perceptively gathered that we would want to return to Zadoi as soon as possible. Thus, despite the rain, he set off with us to a nearby nomad tent where a truck had just arrived from Zadoi (the only truck that had been this way for several days) in the hope that it might be returning to Zadoi and we could hitch a lift. Walking across muddy pasture we were appreciative of Anju’s unselfish generosity and all his help, especially as the weather was so foul. The atmosphere was charged with electricity and lightening flashing dangerously close. My hair was standing on end due to the amount of static electricity in the air. It felt as though my hair was tingling as though insects were crawling through it.

Our sodden journey to the nomad tent brought little joy in terms of a lift, but gave us the privileged opportunity of being able to enter a large nomadic tent and get an insight into their hardy life, albeit a very damp glimpse. I had read before that “The interior of a nomad tent holds all the family’s possessions. There will be a stove for cooking and boiling water. The principal diet of the nomad people is tsampa and yak butter, dried yak cheese and sometimes yak meat. The tent will also house a family altar with Buddha images and yak-butter candles that are left burning night and day. Next to it is placed a box that contains the family's jewellery and other valuables.” While such a description may be accurate it communicates none of the rawness or reality that we felt being inside such a tent.

Our reception was typically warm and generous as we were presented with chipped enamel mugs of yak butter tea. A leg of raw, dried dzu was placed in front of us with a large knife with which to help ourselves. I was tempted to saw off a hunk of red meat with which to exercise my molars but, fearful of stomach upsets whilst trying to cycle at altitude, decided that discretion was the better part of valour and declined, much to the good-natured amusement of our hosts. Such generosity is commonplace, almost embarrassing, and certainly puts much of our hospitality to shame. The Tibetan nomads, eking out a hardy existence on the exposed plains of Tibet, have little surplus and nothing in the way of comforts, yet they were always happy to give and offer.

The tent itself was large, but threadbare, communal and functional. The floor was bare, muddy ground. The kettle, blackened by years of use, was heated by dried dzu dung on a hearth dug into the ground. The roof had a hole in its centre to let the smoke escape, just underneath some plastic sheeting to keep out the rain, a bucket below to catch the drips and prevent the ground from becoming even more muddy. A bridle hung in one corner, in the other a battered chest of drawers. A woollen bag contained three bleating kids, kept in the warmth and safety until the return of the other goats from pasture. The children were dripping wet, bedraggled, little urchins fighting with each other to have a sip from a can of juice brought from the civilisation of Zadoi by the friendly truck driver. An old woman, neglected, sat muttering in the corner, unaware that she was wearing odd shoes. A barely adolescent boy stood smoking with a cocky self-assurance. The women were quiet, the men dominating the conversation. It was dimly lit, smoke filling the air, not as warm as I had imagined, but shelter from the rain.

Back at Anju’s home we were accepted with similar warmth as bedding was hastily arranged for us in a musty storeroom. We spent the rest of the afternoon in a room best described as their kitchen. It was a poorly lit but warm room, some ten feet by twenty feet, with a brick floor. The walls were darkened by smoke and use, a bed and chest of drawers stood at one end, an antiquated iron stove at the other. The ubiquitous portrait of Chairman Mao oversaw the daily routine. Anju’s wife was constantly busy, incessantly rearranging kettles, bringing pots to boil, heating water, kneading dough, tidying, supplying us with tea. All performed perfunctorily without comment or expression. Anju meanwhile, washed his youngest son with touching paternal care, whilst chatting animatedly to us about the source and also England. He seemed unconcerned by how much of his conversation we absorbed, he was simply glad to have company.

His children were quiet but charming, exuding the same easy-going friendliness of their parents. In all Anju has five children, two girls of ten and six, two boys of four and two and a baby of two months. Such a large family is an indication of the remoteness of Zaqen, in that the party machinery and the policy of birth control are of no relevance out here in the back of beyond. Zaqen is so small and remote that it is difficult to see how it has found its way on to the maps

*

Ian’s early morning frustration at a deflated tyre was perhaps as much a reflection of the fact that today we were having to leave behind the hospitality of Anju and retrace our steps to Zadoi. It was disappointing to be returning to Zadoi as it spelt a lack of progress, a waste of time and effort, and yet having said that I would not have missed the experiences of yesterday for all the world.

“I feel as though we are returning to civilisation,” Ian remarked. “It is odd to think of Zadoi in such terms.” A month ago names such as Deqen and Zhongdian seemed remote, unknown towns in northern Yunnan, the wilds of Tibet beyond our comprehension and possibly limitation. It is easy to forget how our experiences over the past month have changed our perception of size, towns and landscape, that civilisation becomes a relative concept. Whether civilised or not, Zadoi did have shops and hopefully would provide access to Mugxung and the source of the Mekong. It was our destination for today.

Fortified by Mrs Anju’s filling breakfast of beef noodles, the pain of the pass was not as great as yesterday, though I think that it had more to do with the leniency of the Gods and the weather. However, not all was plain sailing for the unfortunate Ian got yet another puncture. He was most unlucky with the number and frequency of punctures that he had and I certainly felt for him. Although I felt that at times it was Fate trying to wind up Ian, knowing that he becomes exasperated, easily flustered and annoyed by such irritations. Easy for me to say as I was not plagued by punctures in quite the same manner.

Rain and mudslides had disfigured the latter stages of the road to Zadoi, rendering it only negotiable in a four-wheel drive. Not surprisingly we passed or saw no vehicle en route. I thought that this was an ominous sign that did not bode well for our chances of making it to Mugxung, locals having expressly told us that the Mugxung road was particularly bad. To make matters worse the weather did not look like abating and as we reached Zadoi we were bombarded by hailstones, once again. Not only hazardous to our own personal safety but also to that of the road.

Cycling back into Zadoi was like coming back as returning heroes. Heads turned, heads nodded knowingly, faces smiled warmly, and people were full of recognition and praise. Even the Billy goats that forlornly wandered the streets seemed to be given a sense of purpose by our arrival and perked up. It was good to be appreciated, nice to have such recognition, but on entering Zadoi I could not help feeling a little deflated. The locals were undoubtedly impressed by our cycle to Zaqen and back, but I still felt that in terms of progress we had achieved little. We had experienced but not accomplished.

Reports, comments, hearsay on the distance and the state of the road to Mugxung had been varied and differing, of little help to us. We did not know what to expect. But what we did know, or at least Ian most certainly did, was that his bike was struggling, gear changes sounding like a turnstile on match day. Ian felt that his bike was not up to the journey, and thus we were going to try to hitch to Mugxung and from there travel to the source by horse, leaving our bikes behind in Zadoi with any unwanted gear.

*

We got up at 6.30 am eager and expectant, hopeful of a lift, assured that we were within reach of the source, that it was only a few days away. However, the morning was far from successful, merely infuriating. It was a trying morning of frustration at the lack of transport and being reliant on others, exasperation at the lack of knowledge and information that we could glean about the road and those travelling on it. A morning of waiting around, of asking jeeps hopefully for a ride, of being continually turned down; an instantly forgettable morning.

Wishing to eradicate such failure from memory, we sought the mind-numbing, escapist entertainment of the big screen. Zadoi’s interpretation of the big screen was very different form that of Odeon, Warner Bros or Virgin. It was more familiar and more intimate. It had more character and came in the unlikely form of a VCD house. Many criticise the Chinese for bringing idleness to the youth of Tibet, and if such an accusation is true then the VCD house must stand accused.

There were three or four rival ‘VCD houses’ in town. Each, with the aid of tinny speakers, blared out the violence of the film currently showing to the otherwise tranquil streets of Zadoi in the hope of attracting the bored, the indifferent or those who genuinely enjoyed such ear-splitting displays of machismo. The films were invariably violent, filled with Triad lawlessness, gang atrocities, or incredible feats of strength and fighting ability. The hero was predictably a muscular individual who never seemed to get hurt and also never seemed to learn any lessons. Heroic, to some barely believable, stunts and brutal moments of fighting prowess were greeted with awe, oohs and aahs, by the vocal and appreciative audience, who were as much a part of the experience as the film itself.

We thus entered a VCD house with some trepidation, fearful of volume and violence. Once our eyes had become accustomed to the dimness, the bare benches, peanut shells and cigarette ends on the floor, we found the proprietor and optimistically asked if he had any VCDs in English. Much to our surprise ‘Titanic’ was produced with a flourish. Armed with peanuts, our popcorn substitute, we settled down to this Hollywood extravaganza.

In spite of the hype and the technical brilliance of the film, it did

not have the desired effect of transporting my imagination away from