Chapter 4 - Southern Laos

The day began with excitement. We were up early, full of nervous anticipation, not only due to the challenge of facing the Vietnamese border authorities for the second time but also due to the thrill of entering Laos. Laos was once known as ‘The land of a million elephants’, but is now little known and has been largely forgotten by the outside world. Hence it has been untainted by the trappings of tourism and it’s quiet friendly people have been left alone. The easy-going laid back attitude of the Laotians was aptly summed up by a phrase of the colonial French that described the differences between their territories in Indo-China and still applies today. ‘The Vietnamese grow rice, the Cambodians watch it grow, the Laotians listen to it grow’. It was the country’s untouched charm that we had read and heard so much about and were fascinated and intrigued by. We so wanted to see the country for ourselves rather than through the eyes of others. Thus we approached the border crossing in trepidation, hoping for a more successful outcome than yesterday.

The border crossing spoke volumes of the differences between Vietnam and Laos. On the Vietnamese side of the border we were confronted by the brusque, dismissive shake of the head that is second nature to surly government officials burdened by bureaucracy. Our passports were subjected to countless checks, as pages were thumbed through with bureaucratic delay, and then thumbed through once more just to make certain. His procrastination was charged with cinematic tension, his performance Oscar worthy. I am sure that the bloody-minded official enjoyed making us wait, the delay making him feel self-important.

But thankfully his performance was for show and with a dismissive grunt and begrudging stamp of our passports we were free to exit Vietnam. In Laos our reception could not have been more different to that of Vietnam. We were greeted by smiles and helpfulness. Pens were proffered to help us fill in forms. Questions were asked in a friendly rather than interrogative manner. Advice on how best to proceed from the border was given freely. There was a discernible change in attitude and service, the Laotian officials being happy and proud to see us enter their country.

The helpfulness of the officials directed us down the road to a bus that was about to depart imminently. We quickly loaded our bikes and panniers onto the roof, tied them down and then boarded the bus. I say bus, but it was more of an articulated lorry-come-bus. There were no windows and there were no seats. Instead there were wooden benches that were barely covered by foam and not designed for tall gangly foreigners. But since we had just paid 8,000 kip for the eight-hour journey to Savannakhet we could not complain about the lack of comfort.

We squeezed awkwardly into a couple of free places, watched by the passive stares of the Laotian passengers. I tried to nod a greeting to an old man, who seemed particularly fascinated by our lengthy embarkation. No reaction. Ian tried to smile at a family in the row in front, but they turned away. The silence and stares of our fellow passengers were not unfriendly, yet I found them uncomfortable, perhaps as I had expected the people to show more warmth.

Once the bus started I quickly realised that their stony silence was not a response to our presence but more an attempt to prepare and concentrate the mind for what was to come. Dust quickly began to fill the inside, not only of the bus but also our mouths, eyes and nostrils. Ian and I coughed and spluttered our discomfort whilst the Laotians suffered in silence. To make matters worse the driver seemed intent on hitting every pot-hole with great speed and disturbing regularity. I cursed his unerring accuracy, for as the bus went crashing into each pot-hole, my spine was viciously jolted and knees made painful contact with the wooden bench in front. Again the Laotians suffered in silence, again we were more vocal in our distress, so much so that our grunting and groaning managed to elicit the odd wry smile from the Laotians. No matter how I tried to sit I could not get comfortable and I could not avoid my knees thumping against the bench in front as we hit yet another pot-hole.

I tried to distract my mind from the numbness of my bum and the soreness of my knees by staring out of the window, watching the Laotian countryside rattle by. That in itself, due to the dust, was no easy task. However, despite the limited visibility, there were many noticeable changes from Vietnam, the deterioration was obvious. For a start the road was dirt, whereas in Vietnam it was tarred. In Vietnam where the rains had washed away sections of the road there were gangs hard at work building up banks and repairing the damage. In Laos such industry was not in evidence. Equally apparent was the aridity of the landscape. The fields looked cracked and neglected. Where previously we had seen water buffalo wallowing blissfully in muddy pools, we saw only dried muddy puddles.

The villages were fewer and further apart. They lacked the industry

and prosperity of the Vietnamese villages. A languid air of defeat seemed

to hang over them. They looked tired and dilapidated. Plastic bags littered

the outskirts. Any sense of purpose, desire to do better rather than

accept the status quo, had long since been eroded by the dust and heat.

We endured the shattering journey and the relentless accumulation of

dust to arrive in Savannakhet some hours later. Savannakhet is Laos’s

second largest conurbation, after the capital Vientiane, with a population

of approximately 140,000. I wanted to call it a city but its size does

not warrant such a description, and might seem a little exaggerated

in view of the fact that it does not have any traffic lights. Sleepy

and peaceful, the streets were narrow and empty. There were a number

of French colonial buildings, with balconies and cast-iron railings

that had seen better days. The dull yellow ochre and peeling paint

imbued the buildings with a decaying decadence that was in stark contrast

to the trappings of Thailand on the far bank of the Mekong.

In Thailand several high-rise buildings stood tall and glittering in the late afternoon while in Savannakhet none of the buildings were modern and none higher than two stories. Savannakhet’s simplicity was stark, emphasising the poverty of Laos and its dependence on Thailand. It was a strange thought that on the other side of a half a kilometres stretch of water was a country so different in terms of wealth, development and attitude.

If it was unsettling to see the division of spoils designated by the river, it was good to back alongside the Mekong, called by the Laotians the “Mother of all Waters”. A sense of purpose had been restored, which enabled us to face the fact that we would have another ordeal by bus tomorrow.

*

We had received mixed reports about buses to Pakse. Some had told us that they left throughout the day whilst others had been adamant that there was only one which left early. We were sceptical of the former view whilst daunted by the thought of an early start. Despite our best efforts to clarify the situation, we were unable to do so. The Laotians knew that there was one bus a day but did not really care about the precise time of its departure, their concept of time being much freer than our obsessive love of punctuality and timetables. We compromised, arriving at the bus station at six a.m. only to find it fully laden and about to depart.

If we had thought that yesterday was unpleasant then the ride to Pakse was sheer hell. The inside of the bus was crammed full. Every inch of space was ingeniously utilised with crates of eggs, squawking chickens, pots, pans, bags and bedding stuffed under chairs and filling the aisle. Each time we stopped those clambering on would defy those already on board shaking their heads at the lack of space and create a niche for themselves and their luggage. In view of the cramped confines and conditions on the bus our scepticism at there being several buses to Pakse a day seemed justified.

In between the crates, heads and armpits, I managed to catch glimpses of the outside scenery. As we clattered southwards the land seemed to become more and more arid. So much so that the landscape outside was red and stunted, reminiscent of the scrub of the African bush and not what I had expected to see in Southeast Asia, even if this was the dry season. The long straight road cut an empty path through the desolate countryside, covering trees and leaves in layers of red dust. Unfortunately the trees were not all that the bus covered in dust, as the inside of the bus quickly began to fill with a fine choking red dust. A dust that choked and harassed every part of the body, clogging nostrils, burning eyes and filling ears and pores. Our hair was so affected that by the end of the journey it was as though we were en route to a Chris Evans lookalike fancy dress party. Days later, despite numerous washes, I would still find traces of dust in the most bizarre places.

The eight hour journey was gruelling, a real test of endurance. People talk about the dangers of the white powder in the likes of South America, but on this stretch of the road in Laos it was the red powder and how much you could stand up your nose. But if we had suffered and thought it bad then what about the driver who must have arms of steel from the constant juddering and jarring of the road. It is said that Laotian bus drivers do not stop shaking for hours after a long journey and many a driver is to be seen without his front teeth, a result of trying to have a well-earned beer on arrival.

In fact a loud hissing revealed that the rear right hand tyre had come off worst. Not that surprising given its condition to begin with. I did not see the changing of the tyre as the frustrating and unwelcome experience that blights the daily commute of most motorists. Instead it was an opportunity to watch and observe our fellow passengers, but primarily to watch the improvisation in the method of changing the tyre. The Laotians did not disappoint. Instead of jacking the bus up, it was reversed onto a wooden block so that the other right hand back wheel was on the block and the flat tyre was off the ground. Simple but effective.

A shower and a beer and we had to contemplate a third and final day’s travel to Don Khong and the border with Cambodia. The decision was whether to travel by bus or boat. The bus was much quicker but given our experience of the last few days it was an easy decision and we opted for the more relaxing boat. This was not simply the soft option but a chance to see more of the Mekong, part of the purpose of our trip.

*

Pakse pier was crowded with pirogues whose owners tried to coax potential passengers down the steep banks and across awkward planks and onto their boats. The boat-owners were not fussy or particular in whom they took on board, pigs and two foreigners bearing bicycles were included. We allowed ourselves to be shepherded onto one boat that we hoped was heading south. As we sat on the tin roof of the boat with our bicycles, surrounded by baskets and household paraphernalia, soaking up the atmosphere of the harbour, it was infinitely preferable to being on the bus.

The early morning sun breathed life and colour into the morning start. There was an air of anticipation among all the passengers, eager to be on their way, to return to family and loved ones. But the boatmen were in no hurry, waiting meant the possibility of more passengers. Those on board disagreed and gently urged the boatmen to slip anchor. Eventually the resolve of some of the boatmen began to break and they languidly poled off. Their movements were slow and unhurried, defying the desire of the passengers to be on their way. Slowly the river stirred into action. With a splutter and roar engines were fired and we were on our way downstream.

The Mekong affords a tranquil easy life to those on its banks. There was little traffic on the river. The odd fisherman in a canoe, two boys of an impossibly young age paddling manfully in a canoe that dwarfed them and a pirogue ferrying passengers amongst whom stood a disgruntled water buffalo. The colourful curved corners of a wat (temple) broke through the green trees lining the bank, children splashed and played in the water’s edge filled with gaiety and laughter. Women wrapped in phaa nung, a Laotian sarong, ran into the water to begin their daily ablutions. A water buffalo wallowed nearby in the cooling waters. Canoes attached to bamboo poles in the river-bed rocked silently. The banks of the river were steep and lined with carefully planted crops and vegetables, protected by rickety bamboo fences. The farmers follow the retreating river with their crops, an age-old system of planting.

As the pirogue pottered downstream it stopped occasionally, to me a point on the river indistinguishable from any other, but to the departing passenger home. Goods, the result of retail therapy in Pakse were carried out by men wading up to their necks in water. Women were helped down the gangplank, babies passed over, little girls went running up the bank to greet their fathers. Money was collected and it was always the women who seemed to pay, they being the ones who hold the purse strings. At one stop, the whole pirogue was surrounded by a wading school of chattering women. Crowned in conical hats, knee high in the water, they thrust forward bags filled with Coca-Cola, tiny loaves of French bread, bags of sticky rice and ping kai. Ping kai is basically grilled chicken on a skewer. It was a frenzied splashing of sale.

Nine peaceful and sunny hours later we arrived at the island of Don Khong, an island of some fifteen by eight kilometres and with a population of around 55,000.

“Sprechen Sie Deutsch?”

We turned round expecting to see a fellow Caucasian, but there was nobody.

“Sprechen Sie Deutsch?” and this time I turned to see that it was a middle-aged Laotian man who was launching this unexpected assault on my unused German O Level. I staggered back through my memory for phrases and all that I could come up with was, “Wo haben Sie Deutcsch gelernt?” He proudly informed us that he had worked in Germany for seven years and seemed about to tell us his life history. But before he got too carried away and exposed my German for what it was, virtually non-existent, I pointed out the fading light to him and asked for directions to Muang Khong, the largest settlement on the island some eight kilometres away. He duly explained the route to us and we headed off in what we hoped was the right direction. Our surprise at hearing German must have paled in comparison to the reaction of the islanders to the two of us cycling past. Their reaction to us pedalling by was almost comical as one man stared in wide-eyed disbelief, another open mouthed in incredulity and another doing a cartoon double take,

Our initial urgency to get there before nightfall was asking too much after a sun-drenched day of relaxation on the boat. We arrived in pitch-blackness. Guided by the noise of a generator and the flickering light that it provided we found our way to a guesthouse. Run by a portly French-speaking Laotian, who had been discerning in his construction and furnishing of his property, it was a sturdy wooden building of eight rooms each with Spartan comforts and a wooden balcony decked with heavy chairs. It was pleasing in its simplicity.

Seated on the veranda, having washed and eaten, it was easy to see how and why the colonial French had been so taken by this area. The sky was bright and clear. The temperature was balmy and the night alive with the sound of crickets. It was wonderfully relaxing and we were both able to bask in its comforts, despite the knowledge that such tranquillity would only be short lived.

*

We awoke late. After three days in Laos we had already acclimatised, enjoying and preferring its sloth to the drive of Vietnam. We had a leisurely breakfast of fresh fruit and then headed further south to the island of Don Det. Here the Mekong is lazy, awash with islands and has a wonderful peace and idyllic charm of its own. The Mekong’s width is almost nine miles here during the monsoon, its greatest breadth in its entire three thousand mile journey. It is known as Si Phan Don or the land of ‘four thousand islands’ for the countless islands and sandbars that lie submerged during the monsoon period, only to appear as the water subsides.

In a small pirogue, no better than a dugout, we charted a dreamy course between tiny islands, a riot of fauna, between larger islands of papyrus and palm. Butterflies fluttered aimlessly past, fishermen darkened by years of reflected rays on the water sat patiently in canoes, bamboo poles straining with sunken basket nets. Plastic bottles bobbed silently up and down, denoting fishermen’s nets. Strange trees with bright red leaves, not unlike the Immortal trees of the West Indies, challenged the green around them. Children splashed noisily, stopping briefly to wave, the wetness of their bodies gleaming in the sun. Three monks in a boat encapsulated the idyll, their orange robes at odds with the greenness of the river.

We abandoned ship, or rather were forced to at Don Det, a tiny island with stilted huts and a solitary basic guesthouse. Having secured ourselves a bed for the night, we set about trying to make our way to the Khong Pha Pheng falls. This involved bargaining, and use of our minimal grasp of the Laos language, i.e. constant recourse to our trusty phrase book, for an extremely unstable two-man canoe. Despite our stuttering Laos we duly arrived at the falls, shaken but not stirred. Our experience of the precarious canoe made me even more appreciative of the balance of the Laotian fishermen who cast their nets standing up. Their balance is remarkable.

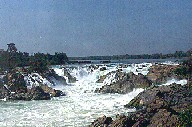

At Khong Pha Pheng, the tranquil waters of the Mekong lose all sense of calm and cascade in a roaring hurry of surging, seething white on to their distant destination of the delta in Vietnam. The falls may lack the height, the majesty of a Victoria Falls, but they are impressive nonetheless. The power of the raging torrent, its swirling strength as it crushes over rocks, pouring from every angle, is in stark contrast to the stillness above. So awed was I, trying to capture its force on film, that I left my Olympus camera lens cap on the rocks: a tribute to the mighty Mekong and the turbulent trauma of Khong Pha Pheng.

It was these falls that had prevented the nineteenth century French explorer, François Garnier from travelling further up the Mekong. Although he was no doubt slowed down by the vast amount of provisions and alcohol that he carried with him.

Khong is an abbreviation of two Lao words that mean “fish waterfall” and fishing is the inheritance of the local people. Fishermen were perched precariously on the rocks netting fish in various ways: some throwing nets, others tending to cane baskets lodged in rushing streams off the river, the unorthodox catch tiny fish in eddies and pools with the aid of a glass bottle. It was obvious that angling on the rocks above the falls was not for the faint-hearted. All were nimble and surefooted, the slightest slip resulting in being swept away by the fury of the foaming waters. The fearless made it to rocks surrounded by raging tides supported only by uncertain bamboo. One fisherman rushed up to the tourist viewpoint after a group of Thai tourists had departed leaving unfinished bottles of beer behind. He guzzled the remnants, obviously in need of sustenance, Dutch courage, before facing the perils of fishing.

The beds that we had secured for the night were on the veranda of a basic guesthouse under hole-ridden mosquito nets. The bedding arrangements were basic but the hospitality was certainly not. The young man in charge was effusive and almost falling over himself in his efforts to please us. After dinner of spicy local dishes, he brought out some Lao-lao, a powerful local brew that is made from sticky rice and is at least fifty per cent proof.

“My mother make,” he said proudly. Not wishing to disappoint Ian and I each had a shot. “Wow” was Ian’s gasped response, tears running down his face. “I wish my mother would make something like that.” He was not wrong, it was so powerful that it almost took your breath away. Lao-lao would be something that we would be steering clear of whilst on the road - a night on that stuff and we would not be able to cycle for days afterwards. When the generator had been silenced, we lay back on our beds in an alcoholic-like trance and enjoyed the brilliance of the night sky above, the stunning array of shimmering stars.

*

We were woken early by the crowing of a blind cockerel. We set off along a narrow dirt footpath, charting an uncertain path between the squeaking, creaking groans of bamboo, the incessant rustling of lizards in the undergrowth, the entangled mass of crawling creepers, the surrounding jungle. We were alone except for the chirpy chatter of birdsong above and the eerie hooping call of monkeys. I longed to spot the source of the singing above, but was denied by the thickness of the canopy above our heads. The only evidence of man was the resourceful requisitioning of rusted rail-tracks to continue the path over streams and gullies (Laos must be one of the few countries in the world today that has no railway).

Still entranced by the ceaseless noise of the jungle, we arrived at Ban Hang Khon, a village on the southern edge of Don Khon. The reason we had come here was to see the Irrawaddy Dolphin. The Irrawaddy dolphin is a freshwater dolphin that does not conform to my stereotypical image of a dolphin, having a bulging forehead and looking more like the much larger Beluga whale.

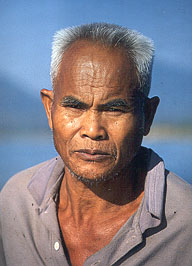

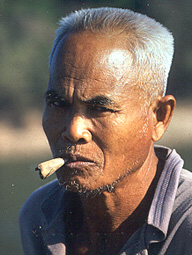

We recruited the services of an old man to take us out to see the dolphins. The old man spoke no English, in fact he hardly spoke at all, simply motioning us to help him edge his canoe into the water. He did not have to as his face and demeanour spoke volumes. His face was wizened and weathered from years spent on the river, exposed to the sun’s rays. His hair was grey, short and spiky. His gaze was stern and penetrating. The triangular hand-rolled cigarette in mouth too large for the corner of his mouth. He was clearly proud of his charges (and the 9,000 kip, approximately £1.50, which our little excursion earned him), for he was content for us to watch the dolphins from the distance of a rocky island. I hope that the old man’s respect lives on after him and that the next generation does not give in to pushy punters and try to pursue the dolphins in his canoe. The locals have a healthy respect for these magnificent mammals, believing them to be reincarnated humans and thus do not deliberately catch them for food or sport. But the gillnets used by the fishermen of today rather than the traditional fish-traps or small hand nets are not as discerning, often entangling and drowning these beautiful creatures.

Wanting to see more of the dolphins we returned in the early evening light. The waters of the Mekong were still, tiny islands quietly dotted around. The sun dying in a blaze of glory, of differing hues, shades of pink, rich orange, wisps of red. The air was still, the mutter of engines far away. Every so often the stillness was broken as the dolphins came up for air. They emerged slowly, their dorsal fins exposed for a few seconds, then slid back into the river. They were not jumping and playful, but slow and languid, like the afternoon sun. It was frustrating because we would hear the swishing release of air and turn to see only ripples. But when we did see a dolphin, its dorsal fin rising majestically, it was a magical calming moment. It was a moment that summed up the attraction of southern Laos for us.

*

We awoke to a brilliant dawn of red and later pink to wish us well for the day’s cycle. We had taken the slightly controversial decision not to take the main road back to Pakse, largely due to traffic and dust, but take a route on the West Bank of the Mekong that would take us along village paths. With the benefit of hindsight it was clearly the right decision but at the time we were both apprehensive, not least of getting lost or not being able to get to Champasak, these paths not existing on any of the maps that we had.

We tentatively headed off to the Northeast corner of the island, some thirteen kilometres away, passing streams of schoolchildren cycling in the opposite direction. Their incredulous looks did little to reassure us that this was a well-trodden path. Arriving at the Mekong we then had to face the problem of how to cross the river, but out of the undergrowth emerged a wrinkled old man who beckoned us to his canoe and for a small fee he saw us safely to the other side.

Once on the western bank of the Mekong, we cycled along small footpaths that connected the villages along the banks of the Mekong. Life here was sedate and as leaves crumpled under our tyres we were able to appreciate how special this unaffected village life was. Scrawny chickens rustled busily in the undergrowth, pigs with incredibly crumpled faces lay idly in the sand, snorting their derision at the heat. Our noses were full of earthy dusty smells, our ears full of the strangled crows of sleepy cocks, the yelping play of puppies and of the occasional dragonfly buzzing angrily by. The sunshine streaming through palm trees gave off a soft golden light that warmed and emphasised the green of the banana trees so that they appeared plastic.

The dusty footpath took us past canoes wallowing in water and the delighted shrieks of naked children playing and splashing in the river. We passed sleepy villages and women wobbling under the burden of buckets of sloshing water. The houses stood tall on stilts with firewood neatly stacked below and washing hung out to dry. Faltering fences of bamboo attempted to enclose livestock. Cooking fires burnt slowly. Amongst the bamboo and the shade there was a soporific timeless air that was untouched and undoubtedly enchanting

We tried to be as unobtrusive as possible not wishing to disturb such tranquil scenes, but invariably our silent progress would not go unnoticed. Young toddlers fascinated by Ian cycling by would step out into the middle of the path only to get the fright of his or her life when I brought up the rear. A young woman grooming her mother’s hair got the shock of her life and uttered a startled cry as we whizzed silently past, only to burst into laughter, amused at her own surprise.

The cycling itself was easy. Palms and trees lining the riverbank shaded the path and the terrain was on the whole flat. The only hazard that we confronted was gullies, a slender log being the only way across. I am sure that the Laotians not only walked across these logs but also cycled across them with ease, without the slightest apprehension. Still relatively new to our bikes and with many more thousands of kilometres to go we were not quite so confident. We opted for the safer but more strenuous option of dismounting, climbing down into the gully and then having to strain and haul our bikes out. It was a dirty and sweaty alternative means of crossing.

Late that afternoon thirsty and covered in dust we arrived in Champasak. Champasak was a sleepy riverside town whose tired colonial buildings with their shutters and balconies revealed that the French used it as a resort. The building work that was going on at present was evidence that the Laotians had similar grandiose schemes to the French and hoped to cash in on the expected influx of tourists. Further threat to the unique way of life in southern Laos that is on the verge of extinction. To be brutally frank my concern for the fate of Laos was overtaken by the desire to wash and be rid of the dust and sweat, to cool down after the heat of the day.

*

Before we set off to Pakse we wanted to visit the religious complex of Wat Phu in spite of the lack of enthusiasm for the site of Goetz a German mechanical engineer who described it as “Just a bunch of ruins.” But then what architectural appreciation does an engineer have and a German one at that. Yet, having been spoilt by the wonders of Angkor we expected little and were merely curious, but we were to find ourselves wrong. I was immediately touched by the attractiveness of the setting, the site nestling at the foot of a hill and rising in a series of tiers into the hillside. The hill’s summit, Phu Khao, commanded my attention because of its shape, identified in ancient times with the linga, the phallic symbol of Shiva.

Two symmetrical buildings of sandstone and laterite marked the beginning of the complex. These buildings are said to have had a religious function but there is little archaeological evidence for this. Their architectural style was reminiscent of Angkor, being built in traditional Khmer style at the height of the empire in the eleventh century. Above on the upper terrace sat the sanctuary, which sheltered the linga and was at one time dowsed with water conveyed from the sacred spring. This permanent spring at the foot of the cliffs was probably one of the main reasons why the ancient Khmer built a sanctuary there. The watering of the linga is a regular feature of the Khmer Hindu religion, but the permanent watering is unique to Wat Phu. The spring filled the complex with character and atmosphere whilst the seven tiers, climbed by a central staircase of seven flights lined with frangipani trees and their white blossom, gave the complex depth and beauty and a lemon-yellow fragrance.

To the north of the sanctuary carved into two separate rocks were an elephant and crocodile. It was the crocodile that got me thinking, especially as my guidebook alleged that human sacrifices were performed on the crocodile stone. It reminded me of the temple of Kom Ombo in the Nile and the ancient Egyptian reverence of the crocodile god Sobek. Kom Ombo once was a stretch of the Nile that was teeming with crocodiles but now due to people pressure and traffic no crocodiles survive in the area. Such is sadly the case with the Mekong around Champasak.

Back in Pakse after the joy of cycling thirty-five kilometres on paved rather than dirt roads we were confronted by a currency in crisis. This was not a calamity that had hit the international markets or Stock Exchange. Most international traders have not even heard of Laos and for them the kip is something they have after a long lunch. The currency crisis had not even been recognised nationally or locally - Vientiane, the capital, had the only newspaper and it did not publish any exchange rates. The fall in the currency was reflected in the black market rate that is used by everyone from backpackers to expatriates. Money can be changed on the black market in shops and restaurants and through the odd moneychanger nervously loitering on street corners. But for the best rate of exchange those in the know, go to the gold merchants, as the merchants need hard currency with which to buy their gold from across the border in Thailand. It is through the gold merchants that we discovered that a month ago you could get 4,000 kip to the dollar but that today the rate was 6,500 - a fifty per cent fall in the currency. We were unsure as to the causes of this currency crash, but did know that it left us with several ‘bricks’ of kip that would further exacerbate our weight problem.

The other challenge that we faced in Pakse that afternoon was trying to obtain fuel for our stove. Due to the fact that there were no settlements of any size between Pakse and Savannakhet, we would have to be self-sufficient and cook for ourselves. The stove ideally uses white gas but can burn on anything from kerosene to aviation fuel. However none of the above existed in our phrase book, so we had to take the stove with us and try to act out what we were looking for. Our performances elicited a number of reactions, usually a bewildered frown and shake of the head, although once one particularly confused shopkeeper ran to the back of his store rummaged around to return with a fire extinguisher. It was us who shook our heads this time.

*

Over the next two days we cycled two hundred and fifty-six kilometres from Pakse to Savannakhet. The road was instantly forgettable for its kilometre after kilometre of dust and dirt, the constant jarring and juddering and the numbing of our bums that were still sensitive to hours spent in the saddle. It was not unlike the bus in that it was trying of humour and temper, but what made the cycling preferable was the contact that we had with the people en route.

The Laotian people were an invaluable source of inspiration, not only on that stretch of the road but throughout our time in Laos. Every hour or so, dependent on terrain, the softness of the sand, the heat and aching limbs, we would pass through a village of reed huts nestling in the dusty foliage at the roadside. A child would inevitably spot us and a cry of greeting “Sabaai dee” would rise up like a siren call, resulting in children emerging form every dwelling, shouting and waving ecstatically as they ran to the roadside. Their excitement was infectious and quickly whipped the whole village into a hysterical frenzy. But all the excitement abruptly came to an end when we stopped. Uncertainty and hesitancy troubled the older children who stood still and stared at us, whilst the youngest would freeze in their tracks with genuine fear, racked by hysteria of a different kind, a wailing and sobbing. Realising that Mum’s threats had not been so idle and that the bogeyman had come to haunt them, they would turn and run to the sanctuary of their homes, never having seen foreigners at such close range before.

The adults more accustomed to falang, the Laotian word for foreigner that was originally used to refer to the colonial French, were merely curious and questioning. “Where are you going?” was their standard question. Our answer of Savannakhet produced a mixture of nods of respect, disbelief and dismissive ‘you must be joking’ laughs. “Where have you come from?” was invariably the next question to which our reply of Pakse would prompt impressed whistles and more disbelief. Further questioning normally revolved around our age and country of origin and almost always whether or not we were married. Our answer to this question of “Yang baw taeng ngaan”, not yet, almost prompted as much disbelief as the fact that we were cycling from Pakse to Savannakhet. In Laos questions about the family are common, almost a part of the ritual of greeting, and the customary response if you are unmarried is ‘not yet’ rather than the dismissive, paranoid scoff of ‘You must be joking’ or ‘No Way’.

It is not just Ian and I that were subject to lengthy scrutiny. Our bikes were also examined at length. Our panniers were pushed and prodded with uncertainty until one of us opened one and revealed the contents to the assembled crowd. Straps were pulled, gears annoyingly changed and brakes pressed. The weight of the bikes or rather the weight that they were carrying was tested and usually impressed. The men acknowledged our efforts and the fact that we must be strong and healthy and motioned to their biceps saying “Baw mii” i.e. that they do not have the strength to do what we were doing. I felt that it was not so much a question of strength but more of time and unhinged inclination.

This is perhaps best explained by quoting from Ian’s diary. “As the poor road and the fatigue (not to mention the sore bum!) went on hour after hour, so my mental attitude deteriorated. I began to see every hill as an effort and irritation. In the darkest moments it became a question of pride and mind over matter to keep going. I kept asking myself what am I doing here and whether or not I was up to it.”

The lengthening shadows and fading light did not augur well for us. We were cycling in the middle of nowhere, without a village or person in sight, thinking that perhaps tonight would be our first night under canvas. Just as we were beginning to despair we arrived at a village and out came the phrase book, “Mii bawn phak you nii baw?” A question difficult enough to say without worrying about getting the intonation right, which hopefully translated as “Is there a place to stay here?”

The man looked sympathetically at us, smiled and shook his head. Had he understood us or was he just shaking his head at our attempts to converse in Laos. I flicked through the pages of the phrasebook becoming frustrated at the amount of worthless phrases that I came across, never the one that we so desperately needed. Eventually I found “Is there anywhere where we can pitch a tent?” and rather than asking him pointed to the phrase in the book. But he couldn’t read. Undaunted he called over a friend who peered at the phrase for an unnecessary amount of time before raising his head and saying “Wat,” and pointing to the Buddhist temple on the outskirts of the village.

The two young monks at the temple were dumbfounded by our arrival, by our presumption that we could pitch our tent in the temple grounds. On the one hand I felt sorry for them, bad at imposing ourselves upon their hospitality, but on the other hand we had few other options. With the help of a mediator to sway them round and persuade them of our predicament, they not only generously offered us the ground floor of the wat but also gave us bedding for the night. We quickly accepted their offer of hospitality before it was withdrawn and made ourselves at home.

News travels fast in the bush and before we knew it a small crowd had gathered to watch us unpack and bed down for the night. They were bemused at my use of a toothbrush to clean the chain of my bike, but the real centre of attention was Ian and the stove. Our whole cooking process was watched with wide-eyed fascination and not a little amusement, no doubt because chores such as cutting vegetables are women’s work. Our gadgetry of the western world, head torch, Leatherman and dragonfly stove, were all bizarre and strange and kept the children from home. I can imagine the scene when they returned home late for supper: “Why are you late for supper?” “Mum, Mum, you would not believe it there are these two big noses at the wat and they have......” “Don’t you lie to me!”

Once the children had gone we were able to enjoy a cup of soup. Seldom has a cup of Tesco’s soup tasted so good. It was certainly better than what was to follow. Our dinner was bland and uninspiring and left us still hungry. Thankfully our cooking skills were to improve with practice, some might argue that they could not have got worse. However the hunger was never to go away.

*

If you had asked me before we had departed this country what we would eat in Laos for breakfast I would not have said baguettes and ‘La vache qui rit’. It might not be my breakfast of choice but they tasted good that morning. Despite our French breakfast with a difference and the good wishes of the monks, the day’s cycle was as unpleasant and tiring as the previous day. But arrival in Savannakhet did mean the luxury of a shower and the reassuring smell of clean hair and clothes. It also meant beers and so we went in search of a late night drinking venue. The only place that was open was brightly lit on the outside, but held the darkest secrets within - the local brothel. We were not charged extortionate prices for the beer nor were we pestered by powdered and perfumed girls trying to sell themselves and their services. Thankfully we were left alone, that is until Noi and his somewhat embarrassed sidekick Nok joined us. Noi was the local policeman granting the brothel a stamp of respectability and the legitimacy of staying open late. He was also full of himself and of our beer. The more beer that he drunk the more that he lost control of all sense of volume, roaring his approval of the fact that we had just cycled from Don Khong to Savannakhet. The evening ended with Noi slumped on the table, trying to salute and slurring Savannakhet. We knew that we would experience much that was interesting and unusual on our travels but did not expect to have to deal with a pissed policeman in a brothel.

*

Our one hundred and twenty-nine kilometres to Tha Khaek was uneventful. In comparison to the previous days it was plain sailing, the roads being wide tarred and free of traffic, scarcely a village or a human in sight. Ian passed the day singing, anything from Les Miserables to Jerusalem, from Meatloaf to U2. I think he thought that I was out of earshot, but unfortunately I was not. Perhaps it is harsh of me to say ‘unfortunately’ especially as I am tone deaf. However I think from the expression on the faces of many of the Laotians, they agreed with me.

Tha Khaek itself was a quiet trade and transport outpost of 70,000 that was being consumed by ice cream and Thailand. We were sat in one of the few restaurants in town when the place was inundated by young people dripping in gold jewellery, all come for ice cream sundaes. It was a horrible version of Bugsy Malone meets Laos and a sad indication that Laos will soon go the way of Thailand, and lose any individuality that it has.

If the tradition of Tha Khaek is being consumed by Thailand then at least this is not so of its geography, yet. More specifically I am referring to the unspoilt limestone formations some fifteen kilometres east of Tha Khaek along highway number twelve. I say highway but that imbues the road with an importance denied by its dust and dirt. If this were America there would be clearly marked trails, a ranger’s office, and shops selling maps and books on the local karst formations. If it were China such scenery would have been immortalised in verse for hundreds of years and now be being spoilt by crowds of camera-crazed Chinese. But this was Laos and the hills were raw and untouched, and until recently largely unknown.

Sheer cliffs of hundreds of feet of limestone blackened by the sun, rose straight up. Craggy sides and rounded summits were covered in dense vegetation. Hidden amongst these sudden hills were a series of caves, many relatively unknown and undiscovered, a potholer’s paradise. Yet this was not so of Thaam Naang Aen whose natural air-conditioning and coolness brought relief from the heat and with it visitors. It was a pleasant spot, a local weekend destination, but the wooden skeletons of various buildings signalled an intention to draw more people. The concrete steps and lighting being built inside the cave revealed the amount of people they hoped to encourage here.

Fortunately Thaam Naang Aen seemed to be the only cave thus affected. Thaam Phaa Ban and Tham Phaa Aen were large echoing caves, hollow and empty, home only to Buddhist shrines. Tham Xiang Liap was similarly free from the tourist treatment. Vast and dissected by a stream, it was home to nothing. There were no sounds or squeaks of bats above as in Tham Phaa Ban, no spoor, no marks or evidence of life. Its silence was eerie and its dark recesses discomforting. My imagination ran riot and I imagined bears to be slumbering in the dark and prehistoric animals to be lurking in the depths of the pools. I was sure that we were about to be attacked and realised that I am not destined to be a serious pot-holer let alone troglodyte.

That evening back in Tha Khaek we were sitting at a small roadside restaurant when we were greeted with, “Hi those bikes must belong to you guys.” The smiling hirsute face in front of us continued, “Hi, I’m Steve from Arizona.” Steve was a larger than life character who quickly signalled his intent for beer and company. He explained how having finished working in Singapore he was taking time out to cycle through parts of Laos, Thailand and Vietnam. If we thought that we caused a stir on our bikes then the twenty stone frame of Steve must really turn heads. Effusive and jovial he must get a warm reception wherever he goes and make many friends. I could imagine him overwhelming a village with his size and humour as he points to his ‘investment’, i.e. his belly, and declares that it is a product of Laos beer. He is a real character who clearly enjoys life to the full, proving that anybody can get out and about, cycle in far-flung places, as long as they have the inclination and will to do so.

*

The one hundred and forty-nine kilometres to Pakkading were uneventful and again relatively smooth thanks to the joys of tarmac. The scenery was rolling, exploding in a forest of vegetation of primary jungle, vines, creepers, trees, and foliage draping the hillsides. Yet the forests were not as green as I had expected, but then they are not true rainforests and thus not evergreen. They are monsoon forests and thus as their name suggests reliant on the seasonal rains, the monsoon, the failure of which last year has caused the land to be parched and dry. Monsoon forests overcome the problem of scarcity of water by having a lighter, thinner forest; indeed most of the trees shed their leaves in the dry season, allowing them to overcome the long periods without rain.

Dipteocarps, tall grey single-trunk trees stood skeletal-like above the canopy of hardwood below, and the shrubs, bamboo and grasses that dominated the ground and floor of the forest. Their sparsely foliated branches stretched out like lifeless coral from the height of the main trunk, their ghost-like grey in eerie contrast to the rustling vegetation below. Lower down bamboo proliferated, the fact that it was fast growing, some species growing up to forty centimetres in a day, helping it to dominate. Bamboo is essential not only to the forest but also for rural life, as the villagers are dependent on it in a variety of ways. Thinner bamboo is used for mat-weaving, floors, walls and roofs, whilst thicker bamboo is used for poles, pipes and rafters

Laos is blessed with vast areas of unspoilt forest and jungle, up to sixty per cent of the country according to some (Laos at 235,000 square kilometres is roughly the size of the United Kingdom). But there are worrying signs of devastation, huge timbers defying the ban on logging and making their way to Thailand and patches of forest scorched by villagers in an attempt to use the land for agriculture. Many Laotians believe that trees are inhabited by spirits and that it is bad luck for a tree to cast a shadow over a house and thus many villages and the areas surrounding them are stripped of trees. But more damaging is the fact that great swathes of land are scarred and scorched by the slash and burn cultivation of farmers who set fire to the forest in order to nitrogenate the soil. This form of cultivation is exacerbated by the fact that many of the farmers are semi-nomadic and move on after a couple of years once the soil has been exhausted of all its nutrients.

The dangers of the ‘match and the machete’ are great. Every second a tropical forest the size of a football field disappears from the planet, mainly by fire. Every year the slash and burn method of farming accounts for the destruction of forest that is the size of Laos, Oregon or Italy. Two-thirds of the forests of Southeast Asia have disappeared already and in sixty years we will have destroyed a forest type that has lasted for sixty million years. As the summer heat increase and with it the dryness, there must be a danger of massive forest fires and massive devastation in many parts of Laos.

The small amount of forest that there was seemed devoid of animal life. The drought and the measly single rice crop each year meant that the villagers depleted the forest of its wildlife in order to feed themselves. This is a problem for conservationists and conservation projects. The government was apparently giving its support, albeit spoken support, to conservation projects and a ban of logging is in place. But the government did not have the means or infrastructure to ensure that their views on conservation seeped through to the villagers. Perhaps more importantly the government was unable to prevent those with an eye to entrepreneurial gain of the moment rather than the landscape of the future.

Reaching Pakkading as the sun was setting we were again faced with the problem of finding somewhere to sleep for the night. We had almost despaired of finding a bed, resigning ourselves to camping just out of town when we were directed to a small restaurant. Shrouded in trees and bougainvillea, the restaurant had a polished wooden floor, heavy teak tables and was very much at odds with the other buildings of Pakkading. We were grateful for this oasis especially as Born Sou, the owner of the establishment, offered us a bed, or rather straw mattress on the floor, for the night.

*

We awoke stiff and sore, not so much from the hard bedding arrangements, but from yesterday’s exertions on the bicycle. At the time, as is so often the case, we thought that we were both fine, but it was the next day, namely today, that the aches and pains of the saddle began to make themselves felt. Our pained expressions and stiff movement spoke volumes and without voicing an opinion on the matter, we agreed by mutual consent to take it easy today.

We took it easy, cycling a mere ninety-five kilometres to Thadok. Despite the fact that we did not push ourselves and that neither terrain nor temperature were too punishing, we did not feel good or relaxed in the saddle all day. Right from the start everything seemed to be a struggle. Everything required effort and concentration. Each molehill was a mountain. Chafed and raw from hours and hours in the saddle it was almost impossible to get comfortable. Even when we stopped for a drink in one of the numerous bamboo stalls en route we were often in too much pain to sit down. We would stand awkwardly trying to rest and relieve sores much to the consternation and amusement of the Laotians.

Ian had the added discomfort of his left hand being twisted and distorted by tendonitis. It had fist caused him pain and discomfort on the road from Pakse to Savannakhet, Ian describing it as like “holding a pneumatic drill for hours at an end”. The luxury of tar had not brought the respite that he had hoped for or eased the stiffness from hours spent gripping handlebars and staring at the road in front. No matter how much he altered his hand positions there were still moments of cramp and discomfort, and what he needed was not tarmac but rest.

Thadok was a collection of eating stalls given substance by the presence of a market, a pharmacy and a barber’s shop. Once again we were spared a night under canvas by Mr Noi who agreed to put us in his house for a small fee. He was young and wealthy; the sale of soft drinks such as Pepsi doing him well (Laos is one of the few countries in the world that I have been to where Pepsi is by far the dominant brand) and this was reflected in his house. Sound system blaring out the latest tunes from Thailand and the Bangkok music industry, the house was of two stories, the bottom of concrete and the top of wood. Downstairs there was a clean squat loo and next door a trough of water with which to splash and wash. Our room, presumably the room of one of his relative’s from the clothes hanging in the corner, was Spartan, foam and straw mats for bedding, but more than adequate.

For food we tried one of the many bamboo stalls in the market. Having eaten fu, noodle soup, for breakfast, lunch and supper for the last few days, we tried to get rice but our attempts were met with “baw mii”, ‘not have’, i.e. failure. But the evening as a whole was far from a failure, as a crowd quickly gathered around us. The chubby smiling woman stall-keeper from next door came over to practice her English but was too shy to pronounce any English words in front of us. This Laotian shyness is undoubtedly endearing and this reserve, their respect for others and their regard for personal space are all part of the charm of Laos. Though this stall-keeper wanted to learn English in order to attract business, to attract foreigners with cash to spend to her stall, she made no attempts to encourage Ian and I to eat at her stall. This is indicative of the hassle free atmosphere in Laos. Walking through a market or past stalls such as these, no attempt is made to kidnap us or press-gang us into the submission of a purchase, instead we are met by happy and warm smiles, if a little reserved and remote.

Kham, a young man sent from Vientiane to work here in what he refers to as the tax department, translated and practised his English on us throughout the night. Mr Phong, a young soldier, repeated the odd English word after us, eager to learn and to try to get away from the routine of the army. Mr Siouw, drunk, smiled inanely and occasionally tried to speak. Every so often he staggered to his feet, uttered ‘Tham’, Laotian for cheers and then tried to clink glasses with Ian, squinting and struggling for balance as he did so. Ian tried to co-ordinate Mr Siouw to do the high five and then ambitiously the reverse low five. This was beyond his drunken co-ordination but caused great amusement for the others. Laughter, as with much of our time in Laos, made the evening.

*

Everywhere in Laos we have seen children rocked in cane cradles suspended from the ceiling or trees by string or rope, with mothers, grandmothers, aunts and older sisters silently rocking babies to sleep. Actually it is a vigorous rocking, a swinging that would unsettle even the most hardened of sea-farers. It is thus a shame that Laos is a landlocked country as after such formative and turbulent years I am sure that many would be untroubled by the rolling of the oceans. As it is they can only wander at the sea and its perils, or gawp in amazement at a film like the Titanic, which sadly has found its way to even here. Why does Hollywood have to confuse and change these wonderful Laotian people with their one-sided stereotypical view of success and wealth? Why does Hollywood try to bemuse the Laotians with films such as Titanic? The sea is a difficult enough concept for them, let alone an iceberg and then an unsinkable ship that sinks.

The ninety-three kilometres to Vientiane saw a slow worsening of the road. Perhaps this was a result of the traffic which noisily increased the closer we got to the capital, but more likely it was due to the fact that it must have been one of the first stretches of road built in Laos and is now in need of repair. With the increase in traffic there was a worrying increase in the number of pharmacies along the roadside. I hoped that there was no correlation and that this has nothing to do with the accident rate.

“Khawy hak jiao,” means I love you

and caused great amusement when I said it light-heartedly to a young

girl who had just arrived to

see what all the commotion was about. We had stopped at a small roadside

stall for a bit of rehydration and to rest numb bums and had become involved

in some good-humoured matchmaking and leg pulling. My declaration of

love further embroiled me in the whole love affair and was met with squeals

of laughter, claps of delight and hysterics. Two older, plumper, matronly

ladies were marshalling the proceedings to the great amusement of those

around, huge broad grins lighting up their faces. We were both aware

of the importance of marriage to Laotians and their wariness of the sleazier

side of Thailand, and thus we were conscious not to offend. But this

was simply fun and yet again proved that the Laotians have a good sense

of humour and enjoy laughter.

|

|

|