Chapter 5 - Vientiane to Luang Prabang

The Vientiane Times ran an article ‘Streetwise’ about the steady, uninterrupted stream of traffic, which offered proof of the ever-growing number of automobiles on the roads of the capital. Mr Duangdy a thirty-two year old traffic policeman was quoted as saying “Road accidents are increasing because the streets are more crowded than they have been in the past. In the morning the roads are usually jammed and there is a big tie up on Lane Xang Boulevard.”

Mr Dungady was not alone in his views for Mr Mongkham a twenty-four year old said, “When cars become too numerous for roads originally built for bicycles and pedestrians, it becomes a big problem. In some ways I think that this is the situation that is facing Vientiane.” Mr Bouonpheng, a forty-four year old doctor, went one stage further and commented on the standard of driving, “I’m more concerned about the large numbers of young people driving while under age or without a proper driver’s licence. What are their parents thinking?”

From such descriptions you might assume that Vientiane is besieged by traffic. Yet in actual fact the traffic of Vientiane is light and does flow, albeit unhurried as with everything in Laos. The problems of Vientiane are negligible in comparison to those of the M25 and the congested streets of London. They are laughable viewed in light of the standstill that cramps the streets of Bangkok in neighbouring Thailand. But for the residents of Vientiane their traffic situation is clearly a problem. Especially when you consider that a decade ago there were few motorised vehicles in the capital and that they had never even heard of the Green Cross Code let alone thought about it. Such problems place Laos in context.

I found Vientiane to be a small capital; after all it had a population smaller than that of Woking. It had only a handful of traffic lights, one newspaper and a small sprinkling of high-rise buildings with nothing exceeding ten storeys. The communists had built concrete blocks that were functional rather than aesthetically pleasing. The colonial French had built wide boulevards and villas, but these had seen better day. This was also true of the drains, which were pungent, stagnant and black. Wobbly and cracked paving stones made them a serious hazard, especially at night with the lack of street lighting.

Yet there were all the worrying signs of development. There was one newly built five star hotel, the extravagantly plush Lao Plaza Hotel, a Scandinavian Bakery, a Danish Church Mission to whet the appetites of the Scandinavian aid workers. It had a Rugby Football Club that advertised in the Vientiane Times for new “players and non-players” and a group of typically random Hash House Harriers. There several Indian curry houses, a collection of French and Italian restaurants that catered for the taste of the expatriate community, a variety of cafes for the backpackers and everywhere food-stalls for the more spicy local palate.

Perhaps more worrying was the increase in tourists that we saw. Vientiane had many tourists in comparison to northern Laos and especially in comparison to southern Laos. In 1999 the government hoped to attract a total of 700,000 tourists to Laos and one million in the year 2000. 700,000 tourists were probably the total number of tourists that had visited Laos until 1999. The government is trying to change this, for as Mr Sanya, Deputy Chief of the National Tourist Authority, has stated, “The NTA has placed an emphasis on improving tourist organisation and management; streamlining immigration services and improving services for the tourists.” Such commitment is bound to change this easy-going country beyond recognition, but who am I to keep it selfishly in the past.

The government had the commitment but it lacked the finance, and perhaps more importantly the co-operation and inclination of the people. There was no concerted motivation or desire amongst Laotians to seek improvement. They are simple unhurried people who are unused to punctuality, commitment and service. The Laos Immigration Office was indicative of the uphill task that the government faces as an extract from my diary shows.

‘Entering the Laos Immigration Office it was clear that the officers were more interested in their table tennis than tetchy travellers seeking to extend their visas. Customer service was an alien concept to them. They were not rude, merely uninterested.

“How long will it take for a twenty day visa extension?” asked a backpacker.

“Two days.”

“Two days! But you just told the other person that a visa extension took one day to process.”

“He only wanted a ten day extension.”

“Sorry?” questioned the traveller in disbelief.

“You want more time. Twenty days takes twice as long to process as ten days,” said the Laotian officer as if it was blindingly obvious.

Not only that but most poor countries faced with a plummeting currency would demand payment in hard currency, but not Laos. The sign clearly stated ‘Payment in $ or Kip at the rate of 4,200 kip to the dollar.’ As the black market rate was currently 6,300 kip to the dollar, those seeking a visa extension were handing over two-thirds of what they should have been.’

*

Whilst in Vientiane we had two objectives, firstly to obtain a visa for China, and secondly to try to get passage on a boat heading north to Luang Prabang as the road made little attempt to follow the course of the Mekong. In the latter task we singularly failed. Every time we asked the Laotian boatmen stared back at us blankly. For some reason unbeknown to us and beyond our trusty phrase book, no boats were travelling upstream at that time of year. Or at least that was the message that we got. This being the case we decided to travel up to Luang Prabang by road and return by boat.

Next we cycled south past wealthy residences belonging to embassies and various aid organisations in search of the Chinese embassy and hopefully entry visas. The Chinese embassy was formidable and imposing, its whitewashed concrete walls seemed a little over-protective. But to be fair to the Chinese, many of the embassy buildings were of similar stature and security, whilst the American embassy looked as though it could survive a nuclear holocaust. If the Chinese embassy looked formidable from the outside, it was no less so inside. The woman controlling the visa section was very matter of fact and formal. Her authoritarian style and barked orders were very different from the casual attitude of the Laotian officials. Though unsettling, her brusque manner was efficient and hence we would be able to pick up our visas in three days – a remarkable turnaround by Laotian standards.

Three days to process our visas meant three days to kill in Vientaine. Our first stop was Pha That Luang. Pha That Luang, the Great Sacred Stupa, is a symbol of Laos and its most important national monument. I had read in our guidebook that the stupa’s “distinctive shape may have been inspired by the staff and begging bowl of the wandering Buddha” and that legend had it that the reliquary stupa enclosed a breastbone of the Buddha. Considering the number of similar claims throughout Buddhist Asia I was somewhat sceptical, believing Siddharta Gautama to have been of considerable size. The guidebook went on to say “the curvilinear four-sided spire is said to resemble an elongated lotus bud, symbolising the growth of a lotus from a seed on the lake floor to abloom over the lake’s surface”. This was supposed to be a metaphor for human achievement and the eightfold path to enlightenment, nirvana. I could see little such resemblance, in fact for me, despite the history associated with the site and its national importance, I thought that it lacked gravitas and was soulless. Sacrilege to say so, but I found it to be devoid of feeling, merely a concrete monument painted in gold. A monument that was more reminiscent of Laos’s recent Communist past than it’s Buddhist culture.

If I was disappointed by Pha That Luang then I was not so by Vientiane’s oldest temple, Wat Sisaket. Built in 1818 by King Anouvong, I found it to be full of character and charm, very much at peace with itself. There was a wonderful stillness inside the wat, the quiet only disturbed by the squeaky chatter of bats and the cheery chirping of birdsong. The shaded cloisters were soothing and reflective, their interior walls riddled with small niches, six rows of them in all, each housing two tiny Buddhas. Bigger bronze Buddhas, seated and standing, rested on the steps below the walls, most dating from the sixteenth to nineteenth century. There were said to be an impressive 6,840 Buddhas in the cloisters, a total of 8,892 Buddhas in the whole wat.

Worn wooden rafters were supported by ageing wooden pillars of faded red, whilst clay tiles lay sleepily on the roof slowly darkening under the sun. The quiet courtyard was paved and at its centre was the sim. A sim is a sanctuary in a Lao Buddhist monastery where monks are ordained, so-called because of the sima, sacred stone tablets that mark off the grounds dedicated for that purpose. The outside walls of the sim were yellow ochre and surrounded by a colonnaded terrace. Inside the walls bore beautiful faded murals depicting scenes from the Buddha’s life story. The hues were soft and gentle with none of the bright garishness that blighted more modern temples. Quite simply Wat Sisaket was refreshingly old.

Haw Pha Khaew, formerly the king’s personal place of worship, was no longer a regular place of worship and hence it had lost the title of wat. A wat is literally a Buddhist compound where monks reside, hence in the case of Haw Pha Khaew no monks, no wat. Haw Pha Khaew aspired to the heavens with cathedral-like height, presumably to emphasise the importance of this royal temple. Dragons with cement scales lay on curved banisters. Imposing columns, decorated with intricate patterns, were wide and high. But it was the silent peaceful bronze statues that watched out over the colonnaded terrace that really caught my eye. They had a timeless quality that was engaging. Their serenity seemed to encapsulate something of the charm of Laos.

Wat Ong Tu is said to be one of the most important wats in Laos. Originally the compound of Ong Tu included nearby Wat In Paeng, Wat Mixai and Wat Hai Sok, but the construction of roads in the city meant the physical separation and break up of the wat into four separate entities. It was a reasonable wat as wats go but after a while they all tend to blend into one. What really caught my eye was not the bronze statue of several tons that the wat was named after, literally ‘heavy Buddha’, but the four armchairs, the black leather sofa and electric fan that were inside the wat. Abstinence was clearly not in the vocabulary of the monks of Ong Tu.

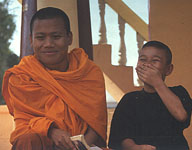

Vientiane is a city of wats and after a while they all began to blur into one. That was until I arrived at Wat Hai Sok. Wat Hai Sok stuck in my memory not for its architecture, but because of a monk, Pornsay. Our conversation initially exchanged pleasantries, the fencing of polite questions. He patiently explained that there were twenty-seven monks and two abbots in this wat, and that his ordination ceremony had lasted for an hour but the partying of his friends and family had gone on for days. He had become a monk when his grandmother died. He talked and asked about England and it's weather. When he told me that his English language book had cost 30,000 kip, bought for him through the generosity of his relatives, and that he wanted to go and join his cousin in Canada, I became sceptical of his devoutness and cynical of our conversation.

But suddenly everything changed when he asked me if I had a girlfriend (but not for the reasons and reactions that that question normally raises). I said yes and jokingly returned the question. Pornsay laughed at my jest and countered, “Do you think I can have a girlfriend?”

“No.”

“You are wrong.” I looked quizzically at him. He continued, “I can have a girlfriend, but I may not.”

His eyes, creased and smiling, beamed his delight at his mastery of English and his sharpness. Pornsay was much brighter than the other monks whom I had conversed with, more articulate, with a lively cheeky wit. He quickly flashed his humour and smile again when he wrote down his name for me.

“Bad sex film,” he said with a naughty twinkle in his eye as he pointed to the first four letters of his name.

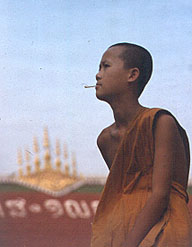

He talked animatedly about his desire to improve his English, yet at the same time wishing to remain a monk. He chided some of the novices, “There are many who become novices for a short time. They do not want to be a monk, be a Buddhist. They come to the wat so that they can have free English lessons with the monks. When they know English, they leave. Get a job in a hotel, make lots of money.”

He then asked me if I wanted to join his English class. I reluctantly consented, unsure of what I was letting myself in for, but thinking that it would be rude to say no. I was glad that I agreed for the next half an hour, sitting at the back of the class, was a truly magical moment. It was warm and cheering, infinitely more preferable than my days of being a pupil. The ‘class’ was in a corner of a large dusty dark room, illuminated only by the daylight pouring through an open window. Two old, damaged sets of wooden desks and a rickety bench facing a crooked blackboard leaning against the far wall comprised the classroom.

The students, Noi who was nineteen and Fat who was twenty-five, both worked as waitresses in a nearby restaurant. Pornsay described with wonderful frankness how Fat’s name was her nickname. Both were shy and embarrassed by my presence. Yet neither wanted to embarrass themselves or their teacher for their lack of English and were thus smiling and eager to learn.

Pornsay somewhat guiltily explained, “I do not take money from them as payment for the teaching, They give me a contribution towards my own studies and tuk-tuk fares.” A convenient arrangement from which both parties benefited.

Without further ado Pornsay began the lesson, not wanting to waste their time and money.

“Today, Unit 15. ‘How do you feel? I feel great. I feel fine. I feel OK.’”

I personally felt wonderful, enthralled by the charm and quaintness of this improbable scene.

*

Perturbed by the ashen skies and the predicament of Laos’s forests I tried to discover some information and statistics about the status quo of the country’s forests. I went optimistically to the Forestry Office but was palmed off to the National Tourism and Information Office. But I could find no statistics, nothing about the current situation, only the ancient and outdated party line: “Laos has one of the most pristine ecologies in Southeast Asia. An estimated half of its woodlands consist of primary forest.”

Being eager to please and not wishing me to away empty-handed the young government official handed me various pamphlets on Forestry and Deforestation. “Forests influence the regional but also the global climate in two ways. First as a temperature buffer and second as a carbon dioxide depot. The forest canopy acts as an umbrella and prevents the soil from heating up in the sunshine, thus buffering the differences between night and day temperature peaks. Likewise, the soil is protected from a direct and rapid evaporation of its water content. The leaves of the trees evaporate water slowly thus adding a constant air humidity. This humidity coupled with lower temperature provides a much lower point of condensation for incoming clouds. Therefore the forests both produce and induce part of the rainfall in their area. Being chopped or burned down, these effects do not exist any longer and the results are shorter, more violent rainy seasons.”

A second pamphlet went on to say that, “Plants, especially trees, transform carbon dioxide into wood and oxygen. Burning or rotting reverses these processes. The combustion of fossil fuels and the destruction of the forest by fire increase the load of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and this is popularly known as global warming.” I did not disagree with the content or the potential educational value of the pamphlets, but I doubted whether these warnings were being heeded. The smoke-filled skies seemed to suggest that the pamphlets were not having the required effect or that the literacy rate in Laos is as low as statistics suggest.

*

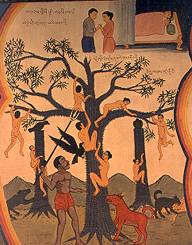

The next morning we made a short excursion out of Vientiane to Xieng Khuan. Xieng Khuan, or Buddha Park as it is more popularly known amongst the travelling fraternity, is a small pleasant park stuffed full of a bizarre collection of weird and wonderful Buddhist statues. The park was designed and built in the late 1950s by a yogi-priest-shaman who merged Buddhist and Hindu philosophy and mythology. The sculptures are made of cement and with no great skill, but they are compelling for their subject matter alone. Buxom ladies with ample breasts and hips stood in coquettish poise, knees flexed, lips big and protruding, features heavy. A man was pulling the leg off a beetle. A man, trident in hand, triumphantly rode on an elephant’s back, busts of men at the feet of the elephant as if they were buried in the ground. A glum faced evil spirit lay on his front, hands either side of his face, which was sprouting bougainvillea, legs like fish tails, scaly and raised in the air. There was a majestic three headed elephant with four armed gods standing atop. A trident wielding man stood menacingly on a turtle. A massive crocodile basked in the sun, mouth open, eyes shut in that deceptive pretend sleep of theirs. A Buddha held his stomach, replete and satisfied.

Some figures were barely one foot high, while others towered above. A monster that looked like something out of a Hammer House of Horror film of at least thirty foot held a maiden in his arms, her head flopped in lifelessness, his clogs heavy, perhaps symbolic of this clumsy helpless giant. A vast Buddha reclined on his side, resting on his right elbow, eyes heavy with sleep. A four-armed god with a feline face, who was pinning a victim to the ground with his right foot, had bougainvillea flowers placed in its mouth as some form of appeasement. Maidens with bowls offered in front of them queued quietly. A Buddha raised his hands motioning to two warring sides, with swords drawn, to stop fighting. A totem of four heads, each with long arms, palms upturned with two-foot statues standing on them, looked like a giant octopus. A massive twenty-foot pumpkin, a sort of primitive rounded spacecraft with square portholes in its side and a spiky coral crown, was guarded by a grotesque face, its bulging mouth the entrance.

The Buddha Park was very much at odds with the harmony of the rest of Laos. The Hindi influence in the bizarre manifestations of gods, the variety was obvious. I preferred the reflective calm of Buddhism and thus returned to Wat Hai Sok to visit Monk Pornsay. This time I was invited to his monk’s cell, an airy room of some fifteen feet by fifteen, not lavish in its furnishings, but then not the Spartan austerity that I had associated with a life of meditation. It was comfortable. Pornsay shared the room with what he described as his ‘monk-mate’ and there were two beds, both with mattress, sheets and pillows. There were two tables each with a fan and a television that Pornsay assured me belonged to his monk-mate. Pornsay’s possessions were hardly puritanical, having a map of the world on the wall, an indication of his intent I mused, and a radio-cassette player. Amongst his tape collection was the ‘Hits of 1980-1990’ including songs such as Joanna Jett and the Blackhearts and Madonna’s irreverent ‘Just Like A Prayer’, hardly songs suitable for soul-searching.

I tried to direct the conversation towards matters of Buddhism and Buddhist life in Laos by pointing to the bowls that the monks use for collecting alms, asking, “For alms?”

“Yes.”

“What do the people put in your bowl?”

“Khao miaw,” the staple Lao diet of sticky rice.

“What is the bigger bowl for?”

“When I am hungry,” quipped Pornsay. In hindsight I realise that it probably belonged to his monk-mate.

We were disturbed by Laotian friend of Pornsay’s who had came to visit or rather to deposit some money for safekeeping. Pornsay dutifully locked the money in a suitcase, which he carefully replaced under his bed. I was amused by the incident, by the implied fact that the best place in town to keep your money was not in the bank but under the bed of a trusting monk. Martin Scorcese eat your heart out as ‘Goodfellas’ meets ‘Kundun’.

*

We were due to pick up our Chinese visas and head north tomorrow, but Ian’s hand was still causing him a great amount of discomfort. The pain that Ian felt is best described in an extract from his diary. “I was suffering from tendonitis, which, by the time we reached Vientiane, had reduced my left hand to a redundant painful claw. Conventional remedies exhausted, I arrived at the dingy door of Dr Soulinthong, the acupunturist, My initial ‘foray’ into his surgery did little to dispel my trepidation and prompted a sharp exit, such was the impression of disorder within. Beyond the filthy chairs which served as a waiting room was a dilapidated screen and a desk piled with medical rubble - books, medicine bottles, and syringes (with and without hypodermic attached). The round-faced Laotian doctor was lounging laconically in a squeaky chair, his bare feet poking through the rubble on the desk. He had wispy black hair tumbling over his wide forehead, which he would sweep away with a jerky motion. His smile revealed a strange assortment of teeth, one of which was certainly dead or dying, and above this his eyes had that slightly wide and glazed look. Having considered the alternatives I returned and, after repeated confirmation that the chunky needles were indeed new, I arranged to proceed.”

“With two needles inserted into the back of my curled hand I was then wired up to a machine which was reminiscent of a wartime wireless. The good doctor flicked a switch on the wall and a jolt shot painfully through my impaled hand. Laughing he twiddled some dials on the machine and the pain eased to a dull, pulsating throb. Far from my conventional stereotype of a medical practice it may have been but after two sessions the problem was resolved.”

Whilst Ian was trying to grapple with the maniacal Dr Soulinthong, I went to exchange some more money. The best rate in Vientiane was not to be found at the gold merchants but form one of the many women who loitered outside the Post Office. These women were easy to spot not least because of the size of the bags that they carried, stuffed full of bricks of kip. They were not usually discreet or secretive about their illicit dealings, but today for some reason there were none of them around, no one approached me. Something was obviously up, but quite what I was not sure. Needing to change money for the rest of our time in Laos, I loitered trying to make myself as conspicuous as possible – not that difficult seeing as I am six foot two inches tall and European.

Eventually after I had kicked a lot of dust about, a smartly dressed woman approached and led me behind a tuk-tuk. As we were discussing rates, she suddenly froze looking behind me. I turned to see myself being filmed on camera. The man happy with his footage, which showed nothing incriminating, turned and went into the ‘Comte Central du Front D’Edification Nationale Laos’. After that, I did not want to go through with the transaction, yet the woman was insistent. Despite a potential three-year gaol sentence the woman was still happy to go through with the exchange – the financial gains outweighing the risk of sentence.

*

The day started with a ‘jambon baguette’ consisting mainly of tuna, a failing of Laotian pig-farmers rather than my Laotian. Baguettes are a legacy of the French and can be bought in the many roadside stalls that proliferate. The stall that we ate at was typical of many that we had seen throughout Laos. Thatched and shaded by blue gums and teaks, it lacked any sense of permanence. A husband and wife team was busy frying fish, doling out rice into small straw baskets, counting baguettes into flimsy, translucent bags that littered most street-corners. In the background Granny was answering to their occasional demand for help, but her primary concern was rocking the baby to sleep. The stall was a scene of quiet, unhurried industry.

After breakfast, I went to pick up our Chinese visas from the embassy. As promised they were ready and waiting. I returned to town to find that Ian had drawn a further blank as to our passage north to Luang Prabang by boat. This thus meant a 156 km cycle for me to Vang Vieng whilst Ian due to the necessity of resting his hand took the local bus, his bike travelling unwanted on the roof. It must have been very hard for Ian not to cycle, frustrating to see me cycle off into the distance, yet it was undoubtedly the correct decision. But it was still a difficult one to make, not least because it meant that we would be separated for most of the next few days. It was strange that on arrival in Vientiane we had wanted to spend time alone, needing a bit of space from each other, but now we were sad to be apart.

I started too late in the day at ten o’clock in the morning. But all was plain sailing at an average speed of over 25kmh until a lunch of watery noodles at Phong Hong. From here the going was steep to say the least and to make matters worse the sun was fierce and unrelenting. As I passed many a Laotian lorry waiting at the bottom of the pass for their radiators and the sun to cool, I thought it only too true that ‘Only Englishmen and mad dogs go out in the noon-day sun’. Foolhardy me pressed on, determined to beat Ian and the bus to Vang Vieng – some hope. The pass was agonising as my leg muscles burned with strain and the sweat poured off me, but what was excruciating was the rolling up and down thereafter. A seemingly never-ending succession of hills had to be crested, and at the top of each there would always be more.

It was backbreaking and exhausting so much so that when I arrived in Vang Vieng at six o’clock I was drained. I was so depleted of energy that for the last hour of the ride, despite the dramatic scenery and great light of a glorious sunset I could not summon the energy to take a photograph. The opportunity was there, so too was the mental inclination, but I was physically too tired to contemplate doing so. However on arrival in Vang Vieng the sight of Ian lifted my spirits. We were glad to be reunited and had a few beers together discussing our various journeys, before the toils of the road did catch up on me and I had to retire for the night.

*

Anywhere else in the world Vang Vieng would be world renowned for its scenery, namely its karst scenery, more specifically its caves. Vang Vieng rivals the scenery of Guilin, which is celebrated around the world as the stereotypical landscape of China with its picture postcard limestone hills, yet few have heard of Vang Vieng. Guilin receives millions of tourists a year is crowded, touristy and inevitably expensive. Vang Vieng receives very few tourists, is untouched by commercialism and in my mind infinitely more relaxing and preferable. The few visitors that Vang Vieng does receive are backpackers drawn here by the combination of the scenery and the prevalence of opium and grass.

Awaking that morning, I found the countryside around Vang Vieng of an intoxicating beauty that I was not able to fully appreciate last night. Isolated vertical hills rose mysteriously from the paddy fields, where villagers laboured and toiled impervious to the scenery that surrounded them. All around, behind, in front, to the left and to the right, hills rose and fell. The peaks and pinnacles were an exotic bizarre manifestation of weather, geography and nature.

Ian and I had decided to take the day off to explore the surrounding

caves, but getting to the caves was an event in itself and symptomatic

of the charm of Laos. The first obstacle was the crossing of a small,

very shallow river: one could either pay 100 kip (one penny) to cross

a rickety bamboo bridge or wade through the river. We chose the latter,

walking amongst children splashing playfully and women trying to net

the green algae floating in the river to sell in the local market. Having

braved such treacherous depths we were guided through parched paddy fields

by a series of bamboo poles. These bamboo poles, crowned with plastic

bags, marked the way to a few of the hundreds of caves in the area, many

as yet unexplored, and were indicative of the state of tourism in Laos,

or rather lack of it.

Our first set of caves was confusingly denoted by a sign that declared “Foreign

country 2,000 kip” – did this mean that as we were from

the same country we only had to pay for one? The caves were a mere

appetiser for what lay ahead, but afterwards they did involve a short

but strenuous hike to what the bespoke guide called ‘Apollo’ or

that is at least what we thought he was saying to us. From this place

of the Gods, on top of the hill, the view was stunning, albeit a little

depressing to see that quite so many fields were lying redundant despite

this being a flood plain and the proximity of the fields to water.

If this were Vietnam or China the fields would be green, irrigated

and fertile, but this is Laos and they are dry brown and barren.

The Palusi Caves were a veritable surprise, hidden a further twenty minute walk through stubble fields and limestone hills covered in thick green foliage. The hand-written sign outside sternly declared “1. No enter cave without permission. 2. Be care hells.” Mindful of doing this by the book and not wishing to upset the spirits, we paid our 2,000 kip (approximately 30 pence) for a guide and cautiously entered the gloom within. Once inside I was immediately glad that I had refused last night’s offer of opium, for we were confronted by a floor of slithering limestone snakes. I had initially discarded the threat of hell and a three-headed Cerberus guarding its gates, believing it to be a mistaken translation, but this seething mass of rock serpents quickly corrected my oversight.

Having braved my initial fear, the caves went on to reveal a multitude of wonders that I still find hard to believe have received so little press, let alone international coverage. Fan coral decorated the cave bed in a fragile wonder of stone, jellyfish hung suspended in motion, draped on the walls were peanuts ripe for the picking, breadfruit hanging heavily, all images of stone. What I naively mistook to be a large pumpkin with stem, our ‘guide’ laughingly referred to as a phallus - male bonding and a little suggestive pointing breaking all barriers of language.

A forest of two-inch high stalagmites covered a slope, reminiscent of the jungle outside. Profiles of faces, a crab’s claw, elephant ears, hanging vines, this cave had everything, even its own orchestra. Several formations when tapped resounded like a timpani drum, others growled like a double bass. When stroked others would sound melodically like a violin. There was even the shape of a trumpet.

To crown it all there was a dinosaur, seen I hasten to add without the aid of opium - you simply did not need such mind bending drugs when faced with such a proliferation and wealth of natural formations. Nature did it all for you. The dinosaur was real, uncannily so, a diplodocus, replete with head, arching neck, four short stout legs straining under its body weight, and a long tail. The one word of English that our guide spoke in English, “Dinosaur”, and a flash of his torch was enough to reveal its immensity.

After lunch we went in search of a bit of rest and relaxation by the Buddha cave and its tranquil pool in which you could swim. Fording the river, we were informed that it was five kilometres away but that the swim was well worth it. However, we were misled by hand-written signs not to the cooling waters by the Buddha cave but to the cavernous Khan cave. There we had an entirely different experience to what we had expected. Here it is not the impressive size of the cave that sticks in my memory, but the tunnels that linked the various chambers together. The tunnels were little over a foot high, claustrophobic and non-laundry friendly. Forced by our earnest guide, we had to squeeze our oversized farang frames through tiny thirty yard long passages, crawling on all fours, stones digging into our hands and knees, shirt and shorts writhing in dust. I felt like Charles Bronson, The Tunnel King, in ‘The Great Escape’.

The hell of the crawling and the cramped space strengthened our determination to find the hallowed charms of the elusive Buddha Cave. Yet it was a further four kilometres down the road, four kilometres of jarring to the wrists and dust in our mouths. En route we had to ford another small river. A short way upstream were some deeper pools where families were performing their daily ablutions. The men were stripped down to their underpants, revealing well-toned bodies not of a muscle-bound gym but the firmness of daily work. The women were more modest and performed their ablutions in their sarongs. Further upstream were some small children, struggling with the weight of ancient jerry cans and plastic containers filled to the brim with water for the evening’s cooking.

By the time we arrived at the pool, we were in need of a swim. Disappointingly, the pool was not the panacea that we desired and far from the oasis that we had expected. Our visions of crystal-clear water were in fact a shallow, cloudy pool that despite our filthy state could not entice us in. Having come so far we could not turn back empty-handed so clambered up to the entrance of the Buddha cave. The first hall or chamber, large and echoing, housed a statue of a sleeping Buddha on a covered dias and hence the name of the cave. This chamber was the first in a series of four, each so huge and cavernous, so deceptively dark that I found it difficult to get an impression of size. There were stalagmites and other fanciful formations but they were crude, not as intricate and subtle as those of the Palusi Cave. Size not detail was the dominant feature.

Back in Vang Vieng and seated under a wonderfully old fig tree, at a bare wooden table on plastic chairs, the lazy quiet simplicity was relaxing and the dust of the road forgotten. Lao Beer in hand, a very drinkable beer, we watched the sun drop slowly behind these enigmatic hills, bathing the sky in a soothing orange. Backpackers swapped stories, passed on information about which was the best ‘den’ in town.

“Go there after ten tonight. It’s awesome. Very mellow.”

“And the gear is good?”

“Yeah.”

“Yeah? How much?”

“It’s dirt cheap. If you come with me I will get you a good deal.”

But for us it was not the company or the substances that made Vang Vieng. We were not indulging in an escapism that was akin to Alex Garland’s ‘The Beach’. It was the scenery and the sunset that night captivated the beauty of the place.

*

Emboldened by our experiences of yesterday, we felt up to exploring a cave by ourselves, so headed out to a beautiful spot on the Nam Song River, a few kilometres south of town. Here the river gurgled playfully over shallow rocks, its water cool clear and enticing. Towering several hundred feet above was the dramatic, sheer face of a limestone cliff. Picturesque and peaceful, it was an idyll to be savoured.

What is more, we had the pleasure of this striking setting all to ourselves. The backpackers were too slow to rise before midday and then they would seek solace in banana pancake before repeating the pattern of yesterday. We were all alone apart from a couple of local boys, whose goggled heads were underwater searching for fish, handcrafted harpoon guns to hand. These homemade guns were of wood, a metal tube to act as rifling attached to the top. They fired a metal bolt by means of a piece of elastic, not dissimilar to that used in a catapult. It was a lethal looking weapon but I felt that its bite was worse than its bark, especially after looking in one of the boys’ small fishing baskets to discover three ‘tiddlers’ that could hardly be described as edible.

Wading knee-high, we crossed the river and entered the cave with some trepidation. Once inside the enveloping darkness of the cave it was easy to become disorientated and made me realise how reliant we had been the previous day on our guide, despite his lack of qualification and linguistic ability. It made the whole experience more eerie, perhaps more of an adventure, but made me realise that my potential as a pot-holer was severely limited. I felt much happier back in the sunlight, exposed to the natural beauty of the area.

I then left Ian with the soporific pleasures of floating downstream in an inflatable tyre, as I set off by bike for Kasi some fifty-seven kilometres to the north. It began as an extremely pleasant afternoon’s cycle ride through charming hills, bright green paddy fields and sleepy villages. Many of the villages were too sleepy and horizontal to be concerned by me. But the enjoyment of looking up at the mystical beauty of these karst hills was short-lived. They shed their appeal as enjoyment turned into endurance and I had to struggle slowly upwards in the late afternoon sun.

Kasi is an unremarkable collection of houses with little to recommend it and I was sure that I was going to have to pitch tent for the night. By chance I stumbled across a guesthouse that had a few presentable rooms, and having negotiated a price of 10,000 kip for the room, settled down to enjoy a cold coke and a night of loneliness and solitude in this small town. But my resignation was not warranted, for much to my surprise two Frenchman, Laurent and Kristoff, appeared from out of the building. Not only could I not believe that there were two other farang in Kasi, but that they were cycling farang. We immediately fell into conversation, swapping stories, giving advice as to the road ahead. As the beer kicked in the barriers went down and so too the tone of the conversation.

*

This foreboding day of 175km began early with a 6.20 am rise and a frugal breakfast of soup noodles, a Milo and a black coffee of potent strength. Duly fortified I set off at 7.20 am grateful of the low mist that was shrouding the stubble fields in a coolness reminiscent of an English dawn. The mist remained keeping the temperature low, but unfortunately not my body temperature. I began to overheat as I slowly began the ascent of the mountain pass. Despite my slow progress sweat poured off me. I use the word progress loosely, because at times it felt as if I was making little headway - after an hour of cycling and much sweating, I was still climbing. At every corner I would long to see a stretch of downhill, the summit of the pass, but at each turn I was cruelly confronted by yet more to climb. It was heartbreaking and soul-destroying, an interminable agony.

If only Dervla Murphy had published her book ‘One Foot in Laos’ before our trip. For in her book she describes the mountain range that I crossed: “I have travelled through quite a few celebrated ranges but none – not even the Simiens – looks as improbable as the free-standing mountains beyond Kasi.” Forewarned with this knowledge I might not have been so ambitious to attempt what I was, cycling from Kasi to Luang Prabang in one day.

In Vientiane we had heard various reports that this road was not the safest, being susceptible to banditry. I had been a little concerned when I set out first thing in the morning and the eerie mist had done little to alleviate my apprehension of being held up. But after a couple of hours I was too tired for the thought to phase me. I was unconcerned by the abundance of ancient muskets on display and the occasional, more modern and more threatening Kalashnikov. I did not give a damn if I was held up; at least it meant that I could stop. Yet, far from being sinister many of these men waved a friendly greeting to me as I struggled past. In fact the only threat they posed was to the birds, hence there being no bird-life in evidence, and themselves. I was certain that the number of men with dodgy or damaged eyes was as a result of misfire from their antiquated muskets, a blast of gunpowder in the face.

Some three hours and forty minutes later, a mere forty-four kilometres, I arrived at Phone Khong and the top of the pass. Here the road splits in two, one fork heading east to Phonsovan and the other on to Luang Prabang. At this crossroads sat a couple of backpackers who had come from Luang Prabang by bus and had been stuck here for twenty-four hours waiting for a connecting bus to Phonsovan. Bored and fed up with waiting, they were amazed to see me.

“Where have you just come from?”

“Kasi,” I panted.

“Where are you going on to?”

“Luang Prabang.”

“When? Tomorrow?”

“Today.”

They look at me with wide-eyed horror. “Are you crazy? You’ll never make it to Luang Prabang today.”

Drained and despondent at this news of the unmanageable distance and terrain to Luang Prabang, I slumped into a noodle stall and greedily slurped two bowls of noodles. As I ate I was grateful for the presence of the itinerant ear-piercer, who was centre of attention rather than my bike and me. Dressed in smart striped shirt and slip-on shoes, with styled hair, the ear-piercer looked out of place amongst the more humble and worn dress of the hill-tribes women. The women stared in fascination, mouths agape, as the ear-piercer took what looked like a staple gun to the ears of the baby girls. The drama of piercing produced wails and tears from all, bar one four year old girl, who with bottom lip trembling clutched the table nervously as she stole herself not to cry. All this pain for the price of 1,000 kip an ear and whilst I was trying to savour my noodles.

Disregarding the warnings of the two backpackers who had not moved from the roadside, I remounted my bike and headed off in the hope, however remote, of reaching Luang Prabang that night. From the reaction and the advice of the backpackers I had expected a succession of rolling hills and was most unamused by the severe climbs that I was faced with. Laos used to be known as ‘The Land of a Million Elephants’, but thus far some 1,200 kilometres of cycling in Laos we had not seen a single elephant. But on this stretch of road from Kasi to Luang Prabang I saw seen at least a million mountains. Perhaps a slight exaggeration but it certainly felt that way.

Eventually at 7.20 p.m. I swept into Luang Prabang, having taken some twelve hours to complete the monumental journey. I remember little of the rugged scenery, which was thankfully shrouded in cloud that kept the sun at bay, and more of the road in front and the physical exhaustion. It was hard going in the extreme, but after a point, having pushed myself so hard and endured so much, I found myself crossing some sort of pain threshold barrier. I simply became more and more focused, more and more determined. I became obsessed by a desire to reach Luang Prabang before nightfall. And I did.

The cycle to Luang Prabang is the hardest day

in terms of being pushed to physical limits that I have had in my life.

Thus I was probably not

too receptive to Ian’s experiences in the bus , wanting only food

and sleep that night and to rest in Luang Prabang over the next couple

of days.

|

|

|