Chapter 6 - Northern Laos

Time stands still in Luang Prabang and the past seems more alive than the present. Nestling between the Mekong and the Khan rivers, Luang Prabang seems to have been forgotten by the rest of the world, a surreal cross between ‘Sleeping Beauty’ and ‘The King and I’ – the jungle protecting this ancient capital from the time-pressure of the present and the chaos of construction. As the populace sleepily potters about its daily business, oblivious to the events of the outside world, Ian and I were won over by the charm of the place and happily agreed to spend a couple of days exploring and indulging.

As I stood at the summit of Phu Si, a hill in the middle of Luang Prabang that gives elevation and appreciation of the town nestling below, it was easy to see why in December 1995 it was made a UNESCO cultural city. The red sloping roofs and upturned eaves peering out from amongst the palm trees, gave the town a charm and laid back feel. The shuttered windows, decaying balconies and charming colonial architecture of many of the buildings lent the city an archaic atmosphere. Around every corner, down each street was something that delighted, that whet the architectural appetite and charmed the cultural conscience.

Not only does Luang Prabang have a timeless charm but it is also infused with a spirituality and calm which is very much a feature of Laotian Buddhism. As with the rest of Laos, the association and presence of Buddhism is strong and is most obviously manifest in the profusion of wats. Wats abound, as do monks who stroll down the streets protecting themselves from the sun with antiquated umbrellas. Every male is expected to spend some time in a wat, usually about three months, and hence the wats are very much a part of everyday life. This sense of community involvement is perhaps most clearly seen in the morning collection of alms.

Slow, shuffling lines of bare-footed silence perambulate the streets at dawn. These mute processions in the gloomy light of early morning are the monks emerging from their wats begging for alms. They take the same route each day and outside their homes the faithful kneel, shoes removed and feet pointing away from the monks, on straw mats, baskets of sticky rice at the ready. There are a few men, but it is mostly women who await the arrival of the monks. As the line of sombre monks file past, shoulders and feet bare and exposed to the cold morning air, they open the lid of their bowl and a handful of sticky rice is placed inside. The monks do not speak a word, their faces are expressionless. There are no nods of appreciation or thanks, just acceptance as the line moves on. Each line represents a wat, varying in numbers from ten to fifty, but despite the numbers there is no noise. When the sun has fully risen the monks return to their wat and only eat what they have been given, their only other meal being at eleven o’clock when summoned by the monastic bell.

Given such an abundance of wats and the fact that we had a couple of days in the town whilst trying to sort out ways of travelling upstream Wat Xieng Thong is perhaps the most impressive of the many wats of Luang Prabang. The sim was small, but gave the impression of wealth and luxury. Its black walls contrasted with the gold and gave the sim a gravitas and provided a depth of contrast. A wonderful tree of knowledge against the red background of the sim’s wall, the wooden rafters, clay tiles and curves lent a gentle air, a mood of reflection. The sweeping eaves of the roof were graceful and soothing, and being low to the ground they granted the sim a homely, down to earth feel. I was surprised to find myself alone inside the sim, but was rudely awoken by the loud ticking of a grandfather clock, strangely at odds with the quiet reflection of the statues and their timeless air. Outside a funerary hall with a heavily decorated door contained what looked to me like a Viking funeral pyre headed for Valhalla, but perhaps I was confusing my religions. It was a funerary carriage with a seven-headed naga at the bow, and a large golden stupa mounted in the middle of the boat.

I found Wat Aham to be an altogether different experience. Inside its walls were typical in that they were covered with bright gaudy murals, but atypical in their subject matter, their blood and gore. There were naked women, men being strangled, people being bludgeoned on the nose with a heavy wooden club, blood spurting out. Another panel was of people impaled on spears, one man particularly unfortunate in the spear’s point of entry, a woman hanging upside down with a spear piercing her back and emerging out of her right foot. The next panel along depicted one man gleefully sawing another man in half, whirling circular saws decapitating victims in the background. Another gruesome panel showed a man having his tongue cut out, another man being suffocated by having sand poured down his throat. All these panels had been painted on July 1991 and I amused myself by thinking that it had been a particularly bad month for the artist rather than a depiction of hell. Wat Khili on the other hand not only has a lethal sounding name but uses bomb shells as flower pots, these destructive weapons of war juxtaposed to the tranquillity of Buddhism.

The Golden Palace or Ho Kham as it is locally known was built between 1904 and 1909, a few years after the Kingdom of Luang Prabang was declared a protectorate and the rest of Laos a colony of France. The palace was meant to symbolise the new relationship between Laos and France, its design containing the French ‘beaux arts’ style with elements of Laos vernacular architecture. However as palaces go it is small and modest, especially the royal residence at the rear and the Spartan bedrooms. The receptions rooms are designed to impress and that they certainly do, leaving me with a feeling that they were painted in poor taste. But the lack of taste shown by the French artist Alix de Fautereau pales in comparison to the walls of the Throne Room, where Crown Prince Sisavang Watthana commissioned a mosaic of Japanese glass against a red background for his coronation. His coronation ceremony never went ahead, perhaps in reaction to the mosaic in the Throne Room.

I was however impressed by the Dong Sun drums lining the corridors. These six hundred to one thousand years old drums had an understated grace, unlike the loud vulgar mosaics. At the centre of each was a sun, then many tiny images decorating the surrounding rings, fish and flowers, frogs and birds. The frogs represent the monsoon whilst all the images together symbolise life, fertility and prosperity. I was tempted to strike one of the drums, curious as to their ancient resonance, but having been told off for going around the museum the wrong way, I resisted the temptation and a further clash with authority. The other room of note was the Prabang room. The Prabang9 is a Buddha image cast in a mixture of gold, silver and bronze with a total weight of fifty-four kilograms. The Prabang has been a chief source of spiritual protection for Laos since it was brought from Cambodia in the fourteenth century, and in 1560 the name of the city, Luang Prabang, was changed in honour of this image.

There is much debate as to whether the image on display in the palace is the genuine article or a reproduction. As with many things in Laos finding out information is difficult, further questions met with blank unknowing stares. Christopher Kremmer in his book ‘Stalking the Elephant Kings’ repeatedly describes his frustration at the ability of officials to avoid difficult questions, their silence and unwillingness to proffer help or information. As with the question of the disappearance of the King and Queen and the crown prince in the late 1970s, the question of whether or not this Prabang is real, is left unanswered. (Debate still rages over whether the royal family were executed in the late 1970s or whether they died of old age or illness whilst in captivity).

*

One of our main concern’s whilst in Luang Prabang was to try to purchase a small pirogue with an outboard engine to take us to Houay Xiay, some three days travel upstream. We had taken the decision to travel this section by boat rather than bike because the road made no attempt to follow the river, meandering east and further into Laos before emerging to rejoin the river at Houay Xiay. We spent several fruitless hours wandering up and down the sandy banks of the Mekong asking in our limited Laotian for a boat to Houay Xiay. On the whole the Laotians presumed that we wanted to go by slow-boat and would point us in the direction of several slow-boats. When we muttered no and wandered off in the opposite direction they were bemused, our actions no doubt further proof for them that ‘these falang are crazy’. The small minority to whom we got the message across to would laugh politely and say no. No doubt even greater proof that ‘these falang are crazy’.

Forsaking the search for a boat to Houay Xiay we settled for a short excursion upstream to Pak Ou. Pak Ou, some thirty-five kilometres north of Luang Prabang, is home to the Tam Ting caves, containing some 4,000 sculptures. The caves, or rather grottoes, lie in the face of a steep cliff overlooking a bend in the Mekong, and were first used by the local population in the worship of Phi, or spirits of nature – the caves were associated with the river spirit. Buddhism entered the valley from China in the north in the eighth century and from the sixteenth century until the dissolution of the monarchy in 1975, the King ad his people would make the annual pilgrimage to the cave as part of the New Year observances. The statue carvings, which date from the eighteenth to twentieth century are made from resin, animal horn and were placed in the cave by worshippers.

The sculptures are in a variety of positions: ‘Calling for Rain’ in which Buddha is standing with his arms pointing downwards; ‘Calling the earth to Witness’, a seated Buddha with one hand extended downwards; ‘Meditation’, hands crossed in front of a seated figure. The figures in the upper cave are more gaunt and slender than other carvings that I have seen. This is partly due to the fact that they are standing, but they are more lithe and graceful, and have an almost aristocratic bearing. Everywhere there are signs that the caves are still used by worshippers today, evidence of melted candle wax, burnt-out joss sticks and dried flowers, the remnants of offerings.

From my rather matter of fact description you might have gathered that the caves are interesting, but certainly not impressive. Far more delightful is their actual situ on the Mekong. It is an area of exquisite natural beauty and half of the charm of the caves is the journey to and from them by boat, if you were to travel by road you would be losing out. Having said that the roaring engines of the speedboats that scream up and down the river frequently destroy the calm of the river. These deafening death traps which are akin to drag-cars on water are noisy and unpleasant to one and all. Helmeted and life-jacketed passengers disembark from these speedboats dazed and disorientated. I am unsure whether their state of shock is due to a loss of hearing or to the number of near misses that they have had – on average there is a fatality each week as these speed machines collide with submerged rocks or logs.

Back in Luang Prabang, seated in one of the many pleasant street-side cafes we enjoyed the luxuries of tea and cake. I browsed through the Vientiane Times and found out that one reason for the pedestrian-like pace of socio-economic development in Laos is that “Lao people don’t learn from each other or other people quick enough”. This is the opinion of Mr Le Cong Ta, Vice Director of the Agricultural Implementation Department of Vietnam. Mr Ta was impressed by many facets of Laotian society believing that the people are honourable, kind-hearted and always ready to help each other in times of need. Neighbours or relatives will accept responsibility for orphaned children as part of one large extended family, something that does not happen in Vietnam.

Comparing Laos to Vietnam, Mr Ta emphasises Vietnamese industry saying that they work hard, save time and expenses and always try to do something more efficiently. “Laos farmers on the other hand live peacefully on their rice plantations and are somewhat oblivious to the potential that exists to do even better.” The general gist of Mr Ta’s argument is that Laotian farmers are less diligent in their work habits and are prone to a way of life that remains far too dependent on the vagaries of nature for survival. In Laos local villagers usually lag behind the habits of the model family because they feel ashamed to ask for advice about how they can better their situation and their lot in life. This is the opposite in Vietnam where people quickly follow suit, everyone learning from one another, thus the country’s agricultural levels are improving more rapidly than those in Laos.

Mr Ta sums up by suggesting that “Laotians do not tend to share information and seem averse to learning from the experience of their colleagues.” His assessment is not only an accurate reflection of the Laotian work ethic, but it also speaks volumes about himself. For me, Mr Ta sounds like a matter-of-fact teacher who does everything by the book. He is correct in one sense, but in another he has missed the point and the charm of Laos, a country that is so laid-back that it calls its currency kip. A country whose very essence is encapsulated in the sleepy charms of Luang Prabang.

*

Whilst Laos P.D.R is known to stand for Laos People’s Democratic Republic, it is more commonly referred to as Laos People Don’t Rush. Realising this and that it might take several days before a boat was found that could take us to Houay Xai, we decided to return to Vientiane by boat. It had always been our intention to travel this section of the Mekong by boat and it seemed to us to be the best use of our time, rather than waiting in Luang Prabang until a boat to Houay Xai could be found.

The boat itself, No 57, effectively its name, was some sixty feet long by ten feet wide. Painted green on the outside, no such luxury was wasted on the inside. The hull itself was metal, the gunwale riding about a foot above the water. Into the gunwale were nailed and bolted some wooden slats, giving a wooden side of some three feet. Light was provided by a series of rectangular portholes kept open by pieces of string tied to nails. The whole boat was covered with a wooden roof and waterproofed by sheets of iron which crunched and clanged noisily above as the crew walked above, much to the annoyance of those below.

At the bow was a seven foot square cabin which served both as the captain's quarters and as the steering house. The metal steering wheel, with its light blue paint peeling off and wrapped in baci strings to keep in the spirits, pulled a chain and series of wire cable and thus the rudder at the stern of the boat. Like the rest of the boat the captain’s cabin was bare, decorated only by a Lee Enfield .303 used, according to the captain, to shoot birds, and a miniature plastic shopping basket containing basic toiletries such as soap, toothpaste and toothbrush. Directly behind the so-called captain’s cabin was an area of planks covered by colourful straw mats, a space for sleeping. Then there were a number of bags of sand, presumably for ballast, another space for sleeping for those with curvature of the spine. Then came the bags of chillies and other cargo that was being transported for some to make their fortune. Aft of the chilli was a roaring Isuzu diesel engine, lovingly watched over by eighteen year old Fu Bok, who would pour water over the propeller shaft to keep it cool, fiddle knowingly with valves and cover holes of hissing steam with oily rags. Behind the engine was an area for the crew to sleep, straw mats on wooden planks with a minimum of bedding, stowed away carefully each morning. Then a ‘space’ for cooking and it was literally that, only a few bowls and dishes giving away the secret kitchen. At the very stern was a toilet of rabbit hutch proportions, its small rectangular hole looking down on the fleeing waters of the Mekong was only for the sure of shot.

The crew were a tight-knit bunch of few words, of shared experiences and time spent on the river. Each had their own role on the boat but they also shared chores, working well as a team. Whenever the pace of the engine slowed, a sign of rapids ahead or that we were going to shore to pick up potential passengers, they would leap into action, manning their respective stations. A tinkling of the bell would indicate to Fu Bok that he should put the engine into neutral. A further tinkle that he should turn it off. The flagpole at the front of the boat, proudly displaying the Laotian flag, doubled up as a measure of the depth of the river, gauged according to the red and white bands painted on it.

As we chugged down the Mekong, gurgling and brown, I was struck by the

depth of the river, or rather lack of it. Rocks and sandbanks were exposed

by the retreating waters of the Mekong, like the cataracts at Aswan on

the Nile, left high and dry by the dam. These bare rocks protruding from

the water created Sylla and Charybdis like channels of swirls and eddies.

But the captain was alert to such deception, aware of the disguises and

deceit of the river, and surfed the small choppy rapids with consummate

ease. However at more turbulent stretches of the river he politely requested

that we came off the roof, not doubting his own ability to pilot the

boat safely through but rather our ability to stay on as the boat rocked

and wobbled at the

mercy of the rapids.

Our harbour for the night was a village so small and makeshift that it would not trouble a cartographer. Quiet and untouched, the village was wary of our presence, hardly surprising considering how alien we were. Curiosity emboldened the children and gradually they ventured out of their huts to the open expanse of sand above the water’s edge. Here they were vulnerable and prey to an impromptu game of ‘Big Bad Wolf’, which caused them to scatter in different directions as Ian and I gave chase. It caused much amusement and shrieks of relieved joy when they knew that they had escaped and were free of us. But there was a fine line between fun and fear. If we got too close or even worse ran alongside them they would break down in terror. One little five year old boy was reduced to a quivering wreck of terrified tears as I drew level, even picking up a stone and a stick with which to protect himself, refusing to play thereafter. An unfortunate reminder that although we only meant well and were indulging in what we thought of as harmless fun, we were genuinely frightening and alien to them.

Worn out by their sheer numbers, youthful exuberance and energy, we retired to the boat for food. Along with the other Laotian passengers we knelt on straw mats, legs awkwardly behind us, as the food was placed in the middle. Sticky rice, hip khao, was our staple, supplemented by watery green vegetables in a soup and spiced by a small dish of ground chillies. The art was to grab a handful of the sticky rice from the basket, roll it into a ball and then dip the ball into the soup or chilli, according to preference. As the name of the rice suggests it was a sticky affair, teeth sticking together in loud chewing sounds and fingers littered with tiny grains of rice.

The crew ate at the other end of the boat, but after dinner joined us. The old man asked us who was attached. On discovering that none of us were married he started trying to fix us up with two Laotian women, who seemed nonplussed by the whole affair. The old man realising that there was little future in his role as matchmaker started to sing. I would have loved to know what his song was about, but our Laotian was not quite up to that so we were left to imagine. I think that he was making songs up about the two ladies, or perhaps from the intent rapture of their faces he was weaving them into an old folksong. Such is the romance of ignorance, the truth was probably far more mundane.

*

At first light the boat radio, powered by the engine, was switched into life. Bedding was packed away and sleep rubbed from sore eyes. The harvest of the overnight nets was reaped and hundreds of small fish were prepared for breakfast. Tiny fish, bony and boiled in chillies, served with sticky rice might not sound that appealing or appetising, but at seven o’clock in the morning somewhere on the Mekong between Luang Prabang and Vientiane it tasted good.

Later that morning we stopped at the unassuming village of Ban Phaliep, a further opportunity to terrorise and traumatise the children in a succession of mock charges, but more importantly business for the boat. The crew collected two empty drums that were placed on the roof alongside three others and to be transported to Vientiane to be filled up with petrol and then dropped off on the return journey. The other task at hand was to buy chillies. These are weighed carefully in spite of the sneezing and bought for 2,000 kip per kilo. In Vientiane they are sold for at least 7,000 per kilo giving them a total profit from nine kilograms of 45,000 kip, roughly $45. A nice little earner especially considering that the average annual income in Laos is only $400.

This little trading episode emphasised the fact that the river is still used as a thoroughfare, the people along its banks dependent upon it as a means of transport and trade. For the crew the river is their life, their boat effectively a river bus and the most efficient means by which to get to Vientiane. The river is their bond, their meaning, whilst for Ian and I it is a temporary obsession.

*

We overnighted in Pak Lay where we were joined by hordes of new passengers. The inside of the boat was now crowded and cramped beyond belief. But what particularly struck me was not the amount of people but their silence. Not that silence is uncommon in England, where on the Underground in London everyone is so wrapped up in their own little world, head buried in the latest thriller, glossy magazine or tabloid, having little or no time for the world outside their own personal space. What was surprising about this silence was that it had no literary or written distraction – none of the thirty or so Laotians had any sort of reading material whatsoever and only one had any sort of distraction in the form of a bulky walkman circa 1980. Not only did they have nothing to read, but also unlike Cambodia and Vietnam there was little interest or preoccupation with what we were reading. Perhaps this was a reflection of the statistic that only forty per cent of the population over the age of fifteen is literate.

The only break from their stoical silence was lunch of sticky rice, a delicious cabbage soup and another indiscriminate vegetable dish. Though limited in its variety the food tasted great, being simple and deceptively filling. It made me realise and appreciate the western luxury of being able to eat whenever you want to, being able to raid the fridge and have a quick snack. There were no such pleasures here on the boat and we had to make do with what we were given. I am not sure if I imagined it or it was me going ‘native’ but I welcomed and enjoyed the abstinence, feeling better for it and less greedy. Doubtless when faced with a menu in Vientiane listing a variety of culinary delights my resolve will break returning to lavish tastes and wider waists.

After lunch we clambered up on to the roof preferring the direct heat of the sun to the stuffy stifling air within the boat. Children played happily on the sandy riverbank, making canon balls from sand and water. Slapping and patting these balls into shape they were clearly having fun, unembarrassed by their carefree nudity, except one older boy who had reached the age of modesty his innocence left behind. It was this older boy, in baggy shorts, that soured the happy atmosphere by slapping a ‘cannonball’ against the bare thigh of a younger boy, whose shocked staccato tears were evidence that the cannon balls hurt. Perhaps wracked by guilt and certainly fearful of adult retribution, the older boy tried to soothe and calm the cries of pain of his victim.

Trying to write a few postcards aroused much curiosity. Not due to my spidery scrawl that over the years has attracted much interest for its illegibility and been the bane of many a teacher, but for the postcards themselves. The postcards were of famous Laotian sights, such as Wat Xieng Thong in Luang Prabang and the ‘That’ in Vientiane, but the Laotian teenagers crowding around me had difficulty in recognising them. Now these were well-dressed and well-to-do young men and the fact that they had such trouble in recognising national treasures is indicative of the extent of the problem of education in Laos.

That night we ate once again with the crew and passengers, our ability to eat sticky rice being more assured creating less mess and chaos than previously. Despite the fact that they knew we had cameras, books and clothes, and perceived us to be wealthy, they still shared their food with us. Such generosity is unquestioning and unthinking, coming naturally to these friendly people. After dinner conversation again revolved around the topic of marriage and eligibility for marriage. I flirted with one forty-year old woman, strong and healthy and who had ten children, and play acted putting my arm around her. She shrieked in horror, the others in laughter. Their laughter was spontaneous and unaffected, untouched by any malice or scorn. They will laugh at anything, even a mishap that to our conservative way of thinking is rude and a little cruel.

*

We left our overnight stop of Ban Wan at just after eight o’clock, to the groans and grunts of three men trying to move impossibly heavy logs, armed only with crowbars. “Neung, Saung, Sam,” a grunted one, two, three in an attempted of concerted effort, working in back-breaking unison. It was incredible that they were doing such heavy labour manually (the diameter of these logs were taller than the men trying to move them) let alone actually managing to move them a few inches at a time.

Breakfast was served on board the boat. A real sense of camaraderie had now been fostered by shared passage on the boat as large trays of chilli and vegetables were passed down from hand to hand to expectant mouths. Everybody recovered their small baskets of sticky rice and got stuck in, literally. Crowded round the trays hands dart forth from the circumference to the tray at the centre to swab up some vegetables with a ball of sticky rice. There was no squabbling over the food, just silent concentrated consumption, or at least as silent as eating sticky rice can be. Once everyone had had their fill, the trays were passed quietly back and everyone reverted to their original position of slumber or staring through a tiny porthole at the Mekong.

A heavy fog filled the air again. This smokescreen is caused by yet more forest being put to fire and is a metaphor for Laos. It symbolises the elusive enigmatic nature of the country. The smokescreen allows us glimpses through its shifting rents, bits of vivid and vanishing detail of the landscape and scenery that surrounds, but giving no connected idea of the general aspect of the country. So too with the people. They are friendly and generous but lack warmth and openness, only offering us brief flashes of themselves. This is not just a result of the barriers of language, but something in their make-up and history, lacking the warm-heartedness of an African for example. Laos is a great country to travel in and I have felt privileged to have been here. Yet although we have had an enjoyable time and seen a great deal, we have experienced little and found it hard to get an understanding of this country and its people. It is as though they are distant and wrapped in a smokescreen of their own.

Suddenly there was a stir of movement on the boat, people readying themselves, women brushing their hair, mothers tidying up young ones, people trying to find their shoes and sandals. One young man particularly upset that he was unable to find his football boats that were obviously his pride and joy. It was as though the captain had announced over the intercom, “Good morning Ladies and Gentlemen, we have just began our descent into Vientiane and will be arriving in approximately ten minutes. I hope that you have enjoyed the cruise, the entertainment and food that has been provided. Thank you for travelling with Boat No 57 and I hope that you make us the boat of your choice for your upstream journey.” A sandbank, a wat and a bend in the river had sparked off this rush for readiness in preparation for our imminent arrival.

We said our sad and fond farewells to the crew and the passengers that had been with us most of the way from Luang Prabang. We were both genuinely sorry to be leaving the boat and its crew, having enjoyed their company and the experience of sharing life on the river with them. One happy note was that the young man had been reunited with his football boots, which he was proudly sporting. We hopped into the back of one of the many brightly coloured tuk-tuks and headed into Vientiane, sharing the fare as was the norm with four other Laotians.

In Vientiane our aim was to return to Luang Prabang as soon as possible and head north and upstream. Returning by boat would take the longest time and would merely be retracing our steps. Bus would be a gruelling day, not something that appealed to Ian already having suffered thus. Plane with Lao Aviation, also known as Lord Almighty, was the quickest but most expensive option. A single fare to Luang Prabang was $46 for foreigners, whereas only 42,000 kip or $6 to Laotians. Despite such price discrimination and the horror stories that are inevitably associated with such local airlines, we decided to fly. Not only just to Luang Prabang but we decided to treat ourselves to a detour via Phonsovan

*

As we began our descent into Phonsovan it was noticeable how the ground was scarred and pock-marked with craters, some small like bunkers on a golf course, others deep and large up to thirty feet in diameter. The province of Xiang Khuang, of which Phonsovan is the capital, was one of the most heavily bombed areas during the Vietnam War. Daily bombing raids meant that virtually every town and village in the province was bombed. In total 50% more sorties were flown over Laos than Vietnam, a total of 580,944 sorties. The USA dropped more bombs on Laos than they did world-wide during World War II. If that staggering comparison is not appalling enough, that relates to an average of 177 sorties every day, i.e. a planeload of bombs every eight minutes, twenty-four hours a day, for nine years. But our interest in Phonsovan was not the US bombing and accounting for the fact that it cost the US taxpayer $2 million every day of the Vietnam War, but the enigmatic Plain of Jars.

On arrival in the small one storey building that is Phonsovan airport we were greeted by a Lao Aviation sign that reassuringly announced that ‘All passengers are covered by insurance’. We were both glad to have our feet on terra firma, and once the bureaucracy of immigration, an excuse for form-filling, had been dealt with, we began to bargain with the tuk-tuk drivers for a reasonable fare into town. We were saved the ignominy of paying way over the odds by a Laotian Willem Dafoe look-alike. His name was Seng and he turned out to be not just a guide of quality, but he had a variety of interesting personal anecdotes that he shared along with his easy smile and wit. We quickly became friends.

*

The Plain of Jars are not unlike Stonehenge in that nobody can say with certainty what they were used for. One theory to this archaeological conundrum is that after a military victory the King threw an almighty party and used the jars to brew an outrageous quantity of LaoLao, a rice spirit. Despite the hedonistic attractions of this alcohol theory it seems more likely that they were funerary urns, the larger jars being used to house the remains of the aristocracy and the smaller jars their minions. Human remains found by French archaeologists in the 1920s and 1930s help support the sarcophagi thesis. Seng hedged his bets and informed us that they had a dual purpose, initially for alcohol and then later for burial.

The Plain of Jars is comprised of three sites.

Site 1 being the largest with some 250 jars, ranging in size from 600kg

to one tonne, the largest

being several tonnes, presumably for the benefit of the king. Seng explained

that not only does no one know the age of the jars but that the stone

used to make them is not from the area. Leaving the mystery of Site 1

behind, we arrived at the smaller and in my mind far more attractive

and intimate Site 2. Here there are only some 60 jars, on a hill, protected

by trees rather than exposed on a barren plain as at Site 1. A good site

for what Seng announced as his ‘guesthouse'’. We looked at

him baffled.

“

This is my guesthouse,” he said pausing for effect, then smiling

and continuing, “When I was young I was riding near here when

it began to rain. It rain very hard, so I tie my horse to the tree

and go in this jar (the jar was on its side and thus adequate shelter

for a young boy). I fall asleep and when I wake up the rain is stopped,

but my horse is wet.”

There is a further site, site three. Different from the others, site three is a pleasant walk from the road through parched paddy fields. The walk was scenic, but I did not err to far from the path, fearful of unexploded ordnance - having just seen a team of young soldiers at work with metal detectors in the slow painstaking task of trying to clear the land and render it safe. On our return a soldier stopped us and told to wait, as there was about to be a controlled explosion of a mine. A puff of dust, a hard thud, and one mine cleared, countless to go.

The land in this region is poor enough as it is without the added burden of bullets, bombs and mines to make the life of those in the area more wretched. The land is poor not just from the ravages of bombing, desolate and treeless, but also because of the government's policies from 1975-1985. Seng told us that the countryside suffered during this time, there being little incentive to produce extra, that since then the people have benefited from private enterprise.

If that is the case, the people are still incredibly poor as witnessed

by the Hmong villages of Dong Den and Tha Chouck. Here half-naked children

sit forlornly in the dust, faces caked with dirt, snotty noses. Little

goes to waste, they cannot afford such a luxury. Small grain houses are

raised from the ground precariously perched on bomb casings to prevent

rats. Every scrap of metal is utilised, bomb casings are not only used

as posts, but also as troughs and fencing. Quaint and photographically

pleasing too the tourist, the resourceful Hmong are simply making do

with what little they have.

*

Back in Luang Prabang we wasted no time and launched ourselves into the pressing task of trying to buy a pirogue that would take us upstream. We met up with Khan, who spoke reasonable French, or at least we thought so, and was wearing a Manchester United shirt. We hoped that he would be able to provide us with our own ‘Theatre of Dreams’, for previously he had been very keen to find a boat for us, and in so doing earn himself a nice little commission. But today the news was not good.

“Ce n’est pas possible à acheter un bateau.”

“Pourquoi non? La dernière semaine vouz nous avez dit ca c’est possible.”

“Le government à interdit les etrangers a acheter les bateaux.”

“Pourquoi?”

“C’est dangereux”

I am sure that you have by now realised that our French was limited and that in the wake of numerous accidents the government had forbidden the sale of boats to foreigners. Not only that, but they had gone even further in forbidding the renting of motorbikes and even bicycles to foreigners – yet surprisingly, foreigners are still permitted to travel by speedboat probably the most dangerous mode of transport of them all. This might have been good news to anxious mothers back home, but was disappointing news for us and not in keeping with the spirit of adventure that we wanted. Not to be defeated, we resolved to try until four o’clock in the afternoon, by which time if there was still no boat available we would resign ourselves to travelling north by slow-boat.

As our deadline drew inexorably closer, we chose to resort to desperate measures and enlisted the help of a young novice in our search for boats. If he wanted to practise his English on us, then he could return the favour by asking around for us. When even he met with rejection we realised that our search was futile, and we resigned ourselves to the slow boat and a sunset beer.

*

We had hoped to find a slow-boat without other falang but our plans were once again thwarted. There was only one slow-boat leaving today and we were forced to share it with five Norwegians, a serenading Japanese couple, a trooper of an American and an Englishwoman in her late thirties. As we boarded the boat we had to pay an extra 10,000 kip for each bicycle, on top of the fare of 41,500 kip. A combination of disappointment in the boat and the unfair discrimination against cyclists meant that we kept very much to ourselves, making little effort to converse and enjoying our ‘splendid isolationism’.

As we headed north a jungle of trees and a mass of vegetation rioted on the rolling hills that closed in on the Mekong. The skies were once again misty and grey, reducing visibility to several hundred metres and stifling and silencing the forest. Our passage was slow with the boat struggling up rapids. On several occasions it was seemingly unable to move against the furious flow, merely holding its position and churning out great wafts of black smoke as the engine roared in effort. Minutes ticked agonisingly by and still no headway was made. Just as we were beginning to worry that the strain might be too much for the engine the boat nudged slowly, imperceptibly at first, forward. Then it was free and we rushed on, eating our way up the river.

Our overnight stop was Khama Kong, a steep sandy bank that for all we knew was in the middle of nowhere. Surprisingly there was a guesthouse, or rather a shack built of cane and palm leaves that had beds for 7,000 kip. Given that the previous night in Luang Prabang we had had a double room with a shower for 15,000 kip this was expensive. But it was welcome, especially as there was little else on offer. Similarly expensive but well received were the noodles, which we slurped greedily before retiring for the night.

*

The captain was eager to be on his way and started the engine to chivvy people out of bed. The bleary eyed falang, still half-asleep and unused to such early starts were the last to board the boat. The engine ground into action, ties were unfastened and we were gently poled from the bank and on our way.

The morning mist wreathed the river in a cloud of silence and the broody hills looked quietly down on the perpetual flow below. Rocks, washed over and worn by hundreds of years of water coursing its way to the distant South China Sea, lie bare and exposed to the cold of the morning. There was little warmth in the air and a cold shiver ran down my spine as I huddled, knees drawn under my chin, in an attempt to keep warm. As trees, rocks, eddies and rapids slipped by, my thoughts drifted aimlessly. The enveloping jungle fired my imagination with boyish dreams of adventure, challenges faced and overcome, of animals, tigers faced and elephants ridden. “At such times his thoughts would be of valorous deeds: he loved these dreams and the success of their imaginary achievements. They were the best part of life, its secret truth, its hidden reality… There was nothing he could not face. He was so pleased with the idea that he smiled, keeping perfunctorily his eyes ahead.”(Joseph Conrad)

Women ankle deep in the murky brown waters of the Mekong share similar fantasies as they pan hopefully for gold. Children play happily along the sandy banks, in the dreamy innocence of youth, in which everything is possible. Older children wave as we pass, or bounce happily, arms and legs flapping up and down, aping the clowning antics of Ian on the boat. The stark realities of life, the hardships, troubles and worries seem distant. We spent most of the rest of the day in idle stupor, reading and watching the world or rather the jungle drift slowly by.

“Elephant!Elephant!”, someone shouted excitedly. I looked up from the pages of Conrad to see the backside of a working elephant disappear into the jungle. I felt excitement at seeing the elephant but this turned to sadness when I thought of how Laos had once been renowned for the number of elephants that it had – there are now said to be less than a thousand. For the nineteenth century visitor Henri Mohout travel without elephants simply could not be done. He wrote of the Laotian pachyderms, “Every village possesses some, several as many as fifty or a hundred. Without this intelligent animal, no communication would be possible during seven months of the year, while with his assistance, there is scarcely a place you are unable to penetrate.”

By evening, the brightness of the sun had died, hidden to the west behind the hills, and with the light fading fast the captain was forced to come ashore for the night. There was a village hidden above, amongst the trees, and the captain, duty-bound to his passengers, felt obliged to accompany us and find us lodgings for the night, there being no guesthouse or similar facilities that catered to the needs of pampered tourists. After much asking and many uncertain looks at us, the falang, a few of us were directed to a house. Content with the reed mats on the floor and a small amount of bedding we negotiated a price of 4,000 kip per person.

Undoubtedly it was a charming village, a very pleasant place to spend the night. But I could not help thinking about whether or not it was a pleasurable experience for the villagers. It was certainly profitable for them, but more than that I doubted. There were some eleven falang billeted in various houses across the village, taking over houses and demanding food, bottled water and even tea. We used their water pump to wash in. Nothing unusual about that as they do the same, but one of the girls did so in her bra and knickers, with no regard for offending their sensibilities. The Laotian women always wash, whether in the river or at a pump such as this, wrapped in a sarong. Not only that but we asked awkward questions such as “Mii hawng nam?” ‘Have you a toilet?’ “Baw mii” ‘Have not’ was the baffled reply thinking why could we not just pee against the tree or if the need arose go further afield out of the village.

The house that Sharon, Steve the American, Ian and I were staying in was wooden and raised on stilts like every other house that we had seen along the Mekong. It was basically one large room of roughly twelve foot by thirty foot with a wardrobe about two-thirds along its length that was used to partition the room. The four of us slept in the larger area, whilst the family slept in the smaller third. The family consisted of two young girls of eight and six, who sat and watched us in silent awe, their mother and a sixty-year old grandmother. Although the grandmother said that she was sixty-five, I am inclined to believe her daughter who said she was sixty, especially if senility effects her family as much as it does mine. Like so many other hill-tribes women in northern Laos, the grandmother’s gums and teeth were blackened by the chewing of betel, a compound of areca-nut leaves and lime powder that is chewed as a sedative. I felt that the chewing of betel was not just a sedative but a powerful form of contraception, for her gums were so disgusting that they would not have looked out of place in an old black and white horror film. Her daughter, a young thirty, could not believe that Sharon was forty, either thinking that she was younger than she said she was or that she had not worked hard enough in her life.

Worn out by another hectic day of thought and fleeting images and with conversation exhausted, it was time to retire to bed at nine o’clock, there being little else to do, no further forms of entertainment in this dark village that did not have the luxury of electricity. As we settled down for bed, the family was fascinated by our sleeping arrangements, perhaps believing that Sharon had enough strength and stamina to take on three men at once. Their curiosity was thwarted by the arrival of the grandmother’s one-armed son and his ten-year old son. With them was a friend who did not say a word, but who was absorbed in his own world, meticulously concentrating on his fix. With the tender skill and care of a master craftsman, he tried to mould the silver foil of a cigarette packet (the remains of Sharon’s packet after the father had helped himself). Once fashioned he would burn some narcotic on the foil, inhaling the smoke that it gave off through a small plastic home-made bong. It was an intricate process that became more and more involved the more he smoked, a telling correlation. It was now our turn to watch in curious fascination, trying to figure out what it was that he was smoking. It was definitely not yaa fin, opium, but presumably an opiate of some sort, possibly crack. Not knowing what it was and wishing to preserve parental peace of mind we declined their offers to participate.

*

The next day saw us making our destination, Huay Xai. Huay Xai is a small well-off town, its wealth deriving from Thailand across the bank. The houses along the main street, running parallel to the river, are all sturdy and well built, exuding status and not unlike alpine chalets. The influence of Thailand was obvious in the goods in the shops and the fact that all prices are quoted in Thai baht. This has had a knock-on effect to black market prices with the best rate of exchange that we could find being 6,300 kip, 300 kip lower than further south and a direct result of the need for baht rather than dollars.

Disembarking at Huay Xai there were none of the fond farewells of Vientiane, rather a polite but unemotional thank you to the captain and we were off to find further passage north. But once again we were disappointed, drawing a blank in our hope of progressing further upstream by slow boat. Our only option was to take a speedboat.

*

We awoke in a cold sweat, filled with the dread of our impending trial by speedboat and nervously made our way to the speedboat harbour, a solitary hut on the edge of a village a few miles outside of Huay Xai. After the protracted negotiation of a reasonable fare we climbed aboard. Our speedboat, like all the others, was some twenty feet in length, very narrow as well as shallow, brightly coloured and with a long propeller shaft and deafening engine at the rear. Our bikes and luggage were stored in the bows, then sat Ian and I on a plastic cushion on the floor, behind us the driver, Captain Tong. Clean-shaven and cool he cut a dashing figure in his windcheater, embodying the playboy image and lifestyle of the speedboat driver.

After a numbing hour and a half we pulled up at a small jetty for what we thought was a refuelling stop. I was thankful for the stop, glad to get out of the wind. The sun had not yet risen sufficiently high enough to warm up the day, and thus despite a couple of T-shirts and a fleece, the wind was chilling and biting. In fact it was not a refuelling stop but actually yet another stamp in our passports from immigration and a change of boats. We were sad to be parting company with the suave Captain Tong, but were to shortly to find out that the new captain was full of surprises of his own.

With a mischievous grin, our new captain opened up the throttle and roared off towards Xieng Kok. We quickly discovered why the grin – he maintained his speed at full throttle, barely slackening his pace when we encountered small rapids or worse still the wake of larger boats. As we went crashing through each wave we soon became drenched, the speedboat being very shallow. The gunwale was only several inches above the water, thus no protection against inundation. In the spirit of speedboat mania we laughed the adrenaline laugh of speed, bizarrely getting a buzz from the soaking. At times I felt as though we were entrapped in some sort of mutant video game, the maniacal captain controlling the joystick.

But speed was not all the captain had in store for us. Suddenly without any warning or explanation, we pulled up alongside a sandbank, more of a spit, on the Myanmar side of the river. We tried to ask the captain via sign and mime why we had stopped. To stretch our legs or allow us to say that we have visited Myanmar? He simply put up his hand, urging us to be patient. As a large Chinese slow-boat chugged past, followed by its rolling wake, we thought that he might have been feeling sorry for us and trying to save us from an ever bigger dowsing. But once the wake had subsided, he made no movement back to his boat, but simply stood there staring. He waited and waited, staring at a small deep pond sheltered by the sandbank. Ian and I exchanged concerned looks. The suddenly he sprang into action, pointing at the pond and running back to the boat to begin his home-made pyrotechnics display.

From a padlocked box at the stern of the boat he produced a plastic bag of goodies: several smaller plastic bags, some string, numerous elastic bands, two fuses and two sticks of dynamite – his home-made explosives kit. Disconcerted, Ian and I smiled nervously at each other, shrugged our shoulders and returned to watching with eager fascination. In the bottom corner of a small plastic bag the captain inserted a fuse, holding it tightly in place with several elastic bands. He then began filling the bag with dynamite from one of the sticks. Once full he tied up the plastic bag and looked it over thoroughly, inspecting and making sure that it was watertight. A slight pause as he looked around, and finding what he was searching for he picked up a small stone and began attaching it to the plastic bag with string. He carefully checked that the stone was securely fastened, for which I was grateful. The stone was to enable the dynamite to sink, thus detonating underwater and having maximum effect and most chance of stunning as many fish as possible. From our point of view the stone was to ensure that the dynamite did not explode on the surface with disastrous effect to us.

The makeshift grenade completed, our dangerous captain checked over his handiwork one final time. Satisfied he smiled to himself, casually lit a cigarette, strolled to the edge of the pool and tested the weight of the grenade in his hand. He nonchalantly lit the fuse with his fag and lobbed it into the pond. A short delay of what seemed like several seconds was broken by a loud muffled boom from underwater and a plume of spray was driven high into the air. We stared in stunned silence. Stunned not just from the noise but from the whole scenario that had just unfolded before our eyes. We were roused from our state of disbelief by the shock waves that began crashing on to the sandbank. Though far from dangerous they were swift and powerful and gave me some impression of the power of a tsunami released by an earthquake underwater. The side of a large boulder cracked and slipped slowly into the water, eaten hungrily by the depths.

We were impressed by the explosion, but not the captain who was disappointed by the sight of no fish. Then suddenly his face changed, breaking into a huge grin, when a large four to five pound carp rose to the surface belly-up. He quickly stripped off to his underwear and proudly swam out into the pool to claim his prize.

Half an hour later we stopped again so that the captain could chance his arm one more time. An even bigger explosion, but unfortunately no large fish, only ten or so tiddlers that any self-respecting angler would have thrown back – but when you fish with a grenade self-respect hardly comes into the equation. Unsurprisingly grenade fishing is illegal, but on these quiet unpopulated stretches of the Mekong in northern Laos who is going to police it. Certainly it is beyond the means of an already cash-strapped government. Harmful to the environment it is one more feather in the cap of the speedboat drivers and their fast and free lifestyle, symbolic of their living for the moment, living for today.

The rest of the journey to Xieng Kok was less eventful but it did reveal one of the most beautiful stretches of river thus far. Its beauty was in its untouched naturalness, the virgin primary jungle that was totally devoid of humanity. All around us was a cacophony of sound. The high-pitched hum of the insects, the “kettle’s boiled!” shriek of the cicadas, and the musical variations of the multifarious bird-life, seldom visible in the dense canopy overhead. I was filled with thoughts of exploration and discovery and felt that we really were travelling into the ‘heart of darkness’.

Xieng Kok was disappointingly small; merely a collection of huts and houses that masqueraded as a village, yet it still had an immigration post at which we had to register. The immigration control book only revealed a handful of falang names in the last few months, telling us what we already could see for ourselves, that very few people pass through here. We had expected more of Xieng Kok as it is the last stop in Laos on the Mekong, there being nothing else between here and the Chinese border some sixty miles away, but the size of the village did not really bother us. There was a very basic guesthouse that would give us a bed for the night before setting off tomorrow and that was all that we needed. The river border is not open to foreigners and hence from here we would have to head north-east by bumpy road to Muang Sing and from there into China.

*

Today was a seventy-five kilometre cycle on soft dirt roads through undulating

scenery, dense jungle and hill tribes. We were both slightly apprehensive

about the ride, not because of the terrain, of what surprises the jungle

may hold or the armed hill tribesmen, but because of the excesses of

travel by boat and the backside not being used to constant contact

with the saddle. Needless to say our fitness was not a problem and

the saddle sores thankfully kept themselves at bay. The problem lay

in Ian’s front rack.

An angry shout was the first I knew about the problem. Well it was probably a little more colourful than that but I leave the specifics up to your imagination. One of the bolts on the left hand side of his front rack had sheared causing his panniers to fall off, and more worryingly rendering his rack a tangled mass of metal. One of the joys of any adventure, a journey such as this, is dealing with and overcoming problems as and when they arise. Experience is gained from an adventure or expedition not by being able to cope with the expected, but by being able to surmount the unforeseen, and our initiative and resourcefulness did not let us down. The problem, as is so often the case, initially looked worse than it actually was, and we were able to improvise by bending the metal back into place and fastening the pannier with a combination of bungees and string. The temporary fix was good enough to see Ian into China and cycle for a few days more, but it was little more than that. We would have to send word back home as soon as possible to try to get a new rack sent out to Kunming, to where we would have to detour to pick it up.

When we eventually arrived in Muang Sing it took us by surprise on two accounts. Firstly its size and the amount of hill tribesmen and women that were milling about, and secondly, and to a much greater extent, by the amount of falang that were there. There were numerous guesthouses, all full, and two restaurants with travellers swapping stories in between mouthfuls of pancakes. It was a shock after the quiet and peace of the last few days. Equally shocking was the amount of flesh on display. I am not sure what was more off-putting, the naked saggy breasts of the hill tribes women or the buxom busts and bums of the foreign women about to spill out of baggy clothes that were somehow too tight. If I have given the impression that Muang Sing is a large town then I must just add that it is all-relative in comparison to what we had seen recently. To put its size into perspective at ten o’clock each night when the generators are switched off and the deserted streets cloaked in darkness, herds of cattle are driven along the main street.

*

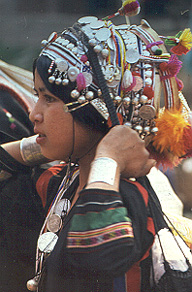

Muang Sing is dominated by its market. Once the biggest opium market in the Golden Triangle, the market is now a blaze of colour and noise as the chatter of barter begins at six a.m. waking weary falang from their alcoholic stupor or Larium-induced dreams. The market is a venue for fresh vegetables, dried cockroaches, meat of dubious origin and a variety of clothes, but it is not the market’s produce that is remarkable but it’s people. The crowds consist of Hmong, Mien, Iko and Akha tribes’ people to name but a few. I could not do justice to the scene as a whole as I am unable to identify or distinguish between the different tribes, unknowing of their colourful dress, but prefer to try to capture the colour in describing the Akha women.

They wear short dark skirts. I say short but they are in fact knee-length, they are not short in comparison to the mini-skirts of the west, but are definitely so in comparison to the sarongs worn by the majority of Laotian women. There tops are also black but emblazoned with bright embroidered trimmings of reds and blues. But it is their head-dresses that are really eye catching, although when they smile revealing teeth blackened by betel one’s attention is also caught but in a less appealing way. Their head-dresses are covered in small white beads, silver buttons and coins. Small pom-poms or plastic flowers sown into the material provide the blaze of colour. Each headers is handmade thus personalised, individual and unique. Their hair is worn piled up underneath the head-dress.

The early morning mayhem of the market over, goods having been bought and sold, a sense of calm and normality returns by eight o’clock. But this peace is not for long, merely a reprieve as the hill tribes women descend upon the bleary eyed falang who are just finishing their breakfasts of banana pancakes. They swarm around trying to sell embroidered bags, cloths and clothes, desperately seeking the foreigner’s money. I think it awful that these once proud women have to demean themselves thus and sell in such an unashamed way, but check myself for fear of being patronising of trying to inject them with my ideals and thoughts. What is to stop them from trying to make money in this way, they are desperately poor and need any source of income that they can get. They need not remain poor, quaint, colourful hill tribes forever merely to satisfy the curiosity of camera and traveller.

A traveller frustrated by the persistence of the women, loses his cool and begins to ape their comments and actions. His comments are initially playful but soon become condescending cruel and unnecessary. Unable to understand the women smile in return, laughing, still hopeful of a sale. This incenses the traveller to further ridicule the women, his grunts and remarks now offensive. It is not right that these women should be subjected to such unpleasantness and arrogance, and I am only grateful that they seem unaffected by such churlish behaviour.

Wishing to get away from such scenes, we cycle out of town towards China, towards the hills and tribes untroubled by everyday contact with falang. En route we stop off at the Integrated Food Security Programme, a government established programme that is trying to support the 10,200 people living in these remote mountain areas and find new means to meet their basic needs in a better way and initiate a sustainable development process. A small, informative exhibition tells of the poverty of the hill tribes and how thirty per cent of the rice that they produce is destroyed rats. It gives details of illiteracy that is at 69% in the area and in one village Muang Mom is at ninety per cent. The programme does provide some direct aid, last year giving 1,200 tons of rice for short-term relief, but its main goal is more long-term, a process of education. The programme tries to teach the villagers about hygiene, that unclean water leads to diarrhoea perhaps dysentery and even death. It sends teams to the 113 villages to immunise the children – a photo of a terrified screaming child testament to such work. Sixteen new schools have been built, three existing schools renovated. But as the exhibition states this educational approach must be linked with activities on the improvement of the women’s social and economic position, on better access to infrastructure, but above all with drug abuse – namely opium.

The opium poppy has been grown in this region for centuries, having been first introduced into China by Arab traders during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1645). The hill tribe minorities in southern China began cultivating opium in order to raise money to pay taxes to their Han Chinese rulers. Many of the hill tribes that migrated to Thailand and Laos to avoid persecution in China or Myanmar brought with them their one cash crop, the poppy, which was easy to grow, flourishing on the steep slopes and nutrient poor soils. The opium trade became especially lucrative in the 1960s when US troops became embroiled in Indo China, not only expanding the Asian markets but also providing outlets to the rest of the world. The area became known as the ‘Golden Triangle’ because of the fortunes amassed by the opium warlords- mostly Burmese and Chinese military-businessmen who controlled the movement of opium across international borders.

Laos is said to be the third biggest producer of opium, after Myanmar and Afghanistan. In 1995-96 one hundred and fifty tons of opium were produced by smallholder poppy cultivation. It is estimated that some 60,000 households in 2,200 villages plant opium, though it is not established what percentage of this reaches market and what percentage is consumed locally. An estimate for the Muang Sing district is that two-thirds of what is produced is consumed within the district. Addiction is thus a problem, not just in terms of numbers (it is thought that some 7,000 people in 1,500 households are addicts among the Akha opium producers), but also the social effects. The value of opium is in its worth as a means of exchange for cash, gold, rice, but the effects of addiction are loss of self-determination and independence. Addiction in men leads to a vicious circle of hunger and poverty amongst households, a reduction in the male labour force, increased work for the women, less agricultural production and it forces the women to hire labour. The Integrated Food security Programme is trying to educate people of the evils of addiction and have introduced a detoxification programme, a fourteen-day course of herbal medicine, including symptomatic treatment by modern medicine if necessary. In 1998 426 people were de-addicted in some fourteen villages. Impressive work but there is still much more to be done and they have an uphill task. Not least in breaking the various local taboos and beliefs about opium, one of which is that it makes you strong.

We continued on our way but after cycling for a while we became particularly sensitive to the villagers and felt intrusive to their way of life. We did not want to gawk and photograph so turned back leaving them undisturbed. On our way back to Muang Sing we passed a small group of smiling children. The young nine year old girl was truly beautiful, lovely innocent smile and laughing eyes. The basket on her back a signal of the hard work that was to come, the loss of the joys of youth. Being a pushover for eyes I agreed to take her and her six year old brother on the back of my bike back to their village, Ian taking their friend. They squealed with delight, whether because of the speed, the bike being preferable to walking, or because it was good to see falang doing the work while they sat behind, I do not know. But I do know that seeing their happiness, the small pleasure they derived from this ride, made me feel warm. I did not feel good because we were helping them, I was just happy to see them so happy.

*

Today was our last day’s cycling in Laos, an easy sixty kilometre cycle to Luang Nam Tha that we took at a very relaxed pace and in a very easy manner, savouring our final look at Laos. I have enjoyed Laos enormously, have found its people to be wonderfully friendly and feel lucky that we have come when we have. That is perhaps something of a cliché statement but the massive influx of tourists that the government is trying to encourage is bound to change the country and make it lose some of its child-like innocence. And yet despite my enjoyment of the country, despite our stay here being pleasurable and interesting, I do not feel that I have come to know the country or its people. Perhaps this is in part due to our lack of Laotian but it is also in part due to the Laotian people themselves – outwardly extremely friendly and charming, but inwardly a little aloof, it being extremely difficult to try to know or understand them better.

Sadly it was time for us to move on, time to try to get into China.

|

|

|