Chapter 7 - Southern Yunnan

A frosty morning with a bit of niggle between us. Me being impatient and wanting to get on the road and reach China, Ian taking his time and unpacking his bags to make sure that no illicit contraband had been planted on him. Maybe we were just sad to be leaving Laos and could not communicate that between us. Our final fifty-seven kilometres of cycling in Laos to the border at Boten involved several climbs up difficult gradients, further ammunition to my argument that Laos should be known as the Land of a Million Mountains, not elephants.

The border crossing on both the Laotian and surprisingly the Chinese side was one of the easiest international boundaries that I have ever crossed. An exit stamp from the Laotian authorities, an entry stamp from the Chinese caused Ian to question, “Is that all there is?” No customs, no questions asked, no checking of our luggage, and yet I would have thought that this border being near to the Golden Triangle would come under much scrutiny. The only remarkable point about the border was the amount of large logs awaiting transport into China and the amount of machinery passing from China into Laos, presumably paid for by the logging, the Laotians having little else to offer the Chinese.

The actual international boundary between the two countries lies halfway between the respective immigration posts, some three kilometres apart, and is marked by a bamboo arch and a small stone monument with China inscribed on one side and Laos on the other. Again unremarkable except for the difference in road quality: the Laotian side is dirt, bumpy and not maintained whilst the Chinese side is tarred, slick and well maintained. The Laotian immigration post is surrounded by a huddle of noodle huts and a small concrete hut masquerading as a bank. “Can we change some money, please?” “No money, no change,” the sad reply. The Chinese immigration post on the other hand is swamped by smart new buildings of tile and blue glass, for which the Chinese seem to have an incomprehensible liking. There were shops full of various goods and a glossy glass building that proudly stated that it is the Bank of China and could change money. The contrast is stark, the difference between Laos one of the poorest countries in the world and China, potentially one of the richest countries in the world.

The difference is not just between the buildings but extends to the countryside, there being a noticeable change in cultivation and techniques. In Laos little of the land is put to use, in China little is not put to use. In China every inch of land is under cultivation, lower down the terraces testifying proudly to the efforts of the farmers, above neatly laid out plantations of tea and rubber. The terraces are like market gardens full of produce, well maintained and cared for, plastic sheeting covering the young vegetables to protect them from the cold. Plastic sheeting is not in evidence in any part of the land in Laos and yet in China its use is widespread. Many of the peoples on both sides of the border are of similar origin and many Laotians have seen the farming methods used in China, but no effort is made to follow suit in Laos itself. As Mr Le Cong, the Vietnamese Vice-Director of Agriculture, pointed out the Laotians seem “oblivious of the potential that exists to do even better.”

There is even a discernible difference to the reaction that we get as we cycle past, or there at least seems to be. The more industrious hard-working Chinese do not smile or wave excitedly at us, some do not notice us, others do not acknowledge us, a few say “hello” in English. It is easy, perhaps facile, to suggest that the Chinese do not have the time to acknowledge us, the life of the peasant farmer being hard. The muted response that we receive may also be due to the fact that there are fewer children in evidence. It would be crass to put this down to China’s ‘one child policy’ for as I will explain in a minute this is a misnomer, but more likely that the Chinese children are at school. Conversely many of the hill tribe children in Laos do not have the opportunity of the access to school. It must also be said that Laotian families are larger, irrespective of the one child policy in China, as infant mortality is much greater hence the need to reproduce at a higher rate and have a large family.

The population of China, currently estimated at 1.2 billion, is bigger than the combined populations of the US, Europe and Russia and the largest in the world, though demographers argue that India will overtake China within the next thirty years. China has historically had the largest or one of the largest populations in the world. In the Tang Dynasty from the seventh to ninth century AD there were ten cities in China with a population greater than one million - after the Black Death in the fourteenth century the population of England was only some 3.5 million. The introduction by the Europeans in the sixteenth century of crops such as maize and peanuts that could be grown on sandier soils, and thus more land could be put under cultivation, led to a population boom. Thus the population of China in the nineteenth century was 450 million whereas the population of Europe at this time was only 250 million.

When the communists came to power in 1949 the population was approximately 600 million. Leaders of China today believe that the optimum Chinese population is 700 million. Mao discarded birth control as a capitalist plot to hinder his country’s growth and said that the strength and potential of the country lay in its people. This rhetoric along with improved sanitation and medical facilities introduced by the communists, and years of stability after the turmoil post 1919 of the Warlord era, the Japanese Occupation of China and the Civil War, led to a baby boom and today’s population.

In the late 1970s the government began to try to deal with the population explosion through campaigns and slogans such as ‘Longer, Later, Fewer’ and billboards showing a young couple with just one child, usually a girl in an attempt to break down established Chinese prejudices. Contraception became free and there was a sustained attempt to educate the people in the use of birth control. The legal age of marriage was raised to twenty-two for women and twenty-four for men, and women were encouraged to have children later by such incentives as longer maternity leave. In the cities married couples were encouraged to sign a one child pledge by offering them an extra month’s salary each year until the child is 14 years old. If the couple has a second child then this and other privileges are rescinded. This policy did not and does not apply to the countryside and to the minorities who are allowed two children before penalties are imposed,

Birth control measures appear to be working in the cities where an extra 300 million people would have been born over the last twenty years had there been no family planning. Yet some argue that if China’s one child policy does succeed than one consequence will be a rapidly ageing population. The argument being that Mao’s baby boom policies created a population that is today young and that the baby bust of today will have the opposite effect, and thus the result will be having to support a large number of geriatrics in the future.

One worrying side effect of the one child policy is the length that couples go to have a boy. Nicholas Kristoff and Sheryl Wu Dunn in their book ‘Dragon Awakes’ talk of how in one province, Zhejiang province, 99% of aborted foetuses were female. Adoption and orphanages are sensitive issues in China but the overwhelming amount of evidence shows that most orphans and adopted children are female. In the countryside where couples are allowed two children if the first is not a boy the girl will often be called ‘Zhaodi’ or ‘Laodi’, variations on ‘Bring a little brother’. This preference, the importance of having a son is deep-rooted within Chinese culture and history, part of the Confucian orthodoxy, and even forms a part of the language. The Chinese character for the word good is . is the character for woman, is the character for son - the implication being that it is good when a woman has a son.

This desire to have a male, a son, has led to a distortion of birth figures. Every people in every country have an approximate birth-rate of ratio of 106 male births to 100 female births. However in China, because of the importance of having a son, this figure has been skewed to 118 male births to every 100 female births. If you extrapolate the world-wide average figure on top of this, this being the norm, then approximately 1.3 million baby girls go missing every year. This raises the ugly question of female infanticide, however most baby girls are simply not reported to the authorities or are left on the doors of an orphanage. Perhaps more worrying for the young men of China there will be a lack of women in the future.

As we neared the town of Mengla the bustle of traffic heightened and the blast of the truck horn deafened. I am not sure whether this anti-social sounding of the horn is to alert us to their presence or to tell us to get out of the way. Given the reckless way in which they drive, the burning smell of rubber as brakes are furiously applied, the manner in which they career around corners in uncontrollable confusion, I fear the latter. The outskirts of Mengla are not unassuming, they are quite simply unappealing. The stench from the rubber plants fills the nostrils, the hum of industry rings in the ears, and dilapidated buildings, a mess of metal and concrete, cloud the eyes.

If the outskirts are grim, the centre in comparison and in spite of the construction is surprisingly pleasant, though immediately alien. Again the omnipresent use of blue glass and tiles (whoever owns the company, or even a company, that produces either must be making an absolute fortune), loud neon signs, signs of ‘OK’ and ‘KTV’ blasting out the tuneless sounds of a warbling karaoke fan. Everywhere people busy about their business. Everywhere there are Chinese characters, an indecipherable script, a meaningless array of symbols in which no concession is made to the bemused, namely the confused and disorientated foreigner.

Our hotel, the Lu Bao Shi hotel, looked impressive from the outside, even its large soulless reception appears grand. Yet it is typically Chinese because, in spite of the outward appearance, the rooms do not live up to expectations. Every Chinese hotel tries to impress with a grand front, but behind this visage is a bland sameness that disappoints and is repeated with worrying regularity around the country. Again, as with every other hotel in China, an attendant looks after each floor with a surly, uncompromising charm that takes years of training and unpleasantness. Although their unhelpfulness does little for the hotel guest, it does wonders for employment figures and is basically a means of jobs for the boys. Or should I say girls, as on the whole they are women. Our room had seen better days and was a little shabby but for 50 yuan we were happy largely because it had hot water, a luxury that we had been denied for weeks. Not that I was at the end of my deprived-of-hot-water tether, but it was just a pleasant change to be able to enjoy and savour a shower.

That night we ate at a local restaurant, a table on the pavement, bones strewn around, watching the world go by. Chinese cooking is justifiably famous around the world and back at home it is no different with food being a national obsession, as evidenced by the common greeting “Have you eaten?” According to various phrase books and guide books this phrase is used commonly as a result of the many famines that China has suffered over the years, most recently the Great Leap Forward when some 40 million people died and the shortages of the Cultural Revolution. And yet I rarely heard this phrase used. Maybe this is due to the fact that there has been surplus since the opening up of the Chinese economy under Deng Xiao Ping and the Four Modernisations of 1978. Or maybe it is just that at the sight of two hungry foreign cyclists the Chinese wished to preserve and save their kitchens from the inevitable and did not ask this question.

Despite the importance of food and eating to the Chinese both at home and abroad, the experience of dining in China is very different from the UK. For a start the menus are almost unintelligible. This is not just due to their use of Chinese characters, but due to items such as ‘mayi shan shu’, which translates as ants climbing a tree but in actual fact is thin spicy noodles, and dishes such as fish heads and chicken feet. Exotica such as snake are available but not as widespread as stereotypes would have us believe, in part no doubt due to the cost of such items. The Chinese food that we get in Britain is largely of Cantonese origin, a lot of sweet and sour and mono sodium glutamate. In China there is not as much ‘sweet and sour’ or MSG, and Sichuan food, hot and spicy, is the most popular of cuisines.

Not only is the food itself different but also the manner in which it is consumed - eating in China is not for the faint-hearted or those obsessed by table manners. Sounds of slurping, noisy slurping that causes you to turn and stare, smacking chewing and occasionally spitting provide the background noise to animated conversations that become more heated as more alcohol is consumed. The end of the meal is a scene of debris and carnage, bottles, chopsticks and spilled food littering the table, bones and cigarettes strewn over the floor, not unlike a drunken student visit to a curry house.

People sat on stools and chairs outside their shop-fronts, chatting and laughing with friends, gossiping and joking. It was all very sociable, life happening on the street-side, lacking the privacy and personal space of the west as everything was out in the open. The meal itself was interesting, if only for the ordering. Presented by a menu written in Chinese I explained in Chinese that I could not read Chinese characters. Amusement at the fact that I could not read then worry and concern that I might not be able to order. I then began asking for various dishes that I could remember and each time received the answer ‘mei you’ which means ‘have not’. At the point of exasperation I was led into the kitchen to see what was available and to witness the killing of a chicken - at least one dish would be fresh.

*

Breakfast Chinese style is no less easy on the stomach or eye with pickled vegetables, rancid dofu and noodles. Breakfast for us that morning was a sombre affair, the sky dull and overcast. The bowls of noodles that sat in front if us with two fried eggs and some meat of questionable origin were uninspiring. The green tea in a pathetically battered plastic mug summed it up. Not the kind of start that we wanted to energise us for the one hundred kilometre cycle to Menglun.

Energy we needed for the ride involved three hard, weary climbs over three different passes. Mao was not wrong when he referred to his country as the ‘land of a hundred rivers and a thousand mountains’. After all he should know having walked for a year and 8,000 kilometres through the country on the Long March in the 1930s. China does in fact have nine of the fourteen highest mountains in the world, though fortunately not along our intended path. Despite the hills there were no hill tribes, only Han Chinese in evidence - the Han Chinese make up 93% of the population, some 1.1 billion, the other 7% consists of 56 minorities of which 23 are in Yunnan, and hence my surprise at not seeing any hill tribes. In spite of the height and the tortuous twisting of the roads, there was still a gang of workers maintaining the road, industry that contrasted with the apathy of Laos.

A solitary roadside restaurant was a welcome break from the peddling. Starving we stuffed ourselves, gorging on rice, potatoes, egg plant, beans and egg and tomato. The couple running the restaurant were impressed with our cycling, responding with an open-mouthed ‘aaah’ of awe as I told them that so far we had cycled over two thousand kilometres. The food was simple but good, their generosity warm and sincere, offering us watermelon and cigarettes to end the meal. The offer of cigarettes, as with the world over, is a sign of friendship and often hard to refuse even after explaining that smoking is not cycle-friendly. The Chinese do not believe this, that it damages the health, and they point to Mao and Deng both heavy chain-smokers and both living a long life into their eighties and nineties respectively. Perhaps this is one reason why there are over 300 million smokers in China, the vast majority of whom are male as women do not smoke or have not done so until recently.

We saw little of Menglun that night, opting instead for the placid surroundings of the XiShuangbanna Tropical Botanical Gardens. Impressive in style and layout with neatly planted areas of bamboo, palm trees and oranges there are a vast array of botanical species in the garden, some 3,000 in all. The gardens were quiet and uncrowded just as was our hotel, an impressively smart hotel that did stand up to further scrutiny, the rooms eminently presentable, but for whose benefit, as they were empty. Was it built with an eye to a future market or just as a spin-off of the construction boom in China? China is construction crazy, every city under scaffolding, every mountainside blasted for rocks, sand and cement - hence en route today with flagrant disregard to the many signs designating the area as a ‘Nature reserve’ there was a gaping hole that had been blasted into the mountainside.

*

The 71 kilometre ride to Jinghong was pleasant and not at all strenuous, the road for the last 24 kilometres rejoining the Mekong, our first sight of it in China. Throughout the ride there was further evidence of the industry of the people, the productivity of the land. In one valley there were piles of peppers, green and red peppers harvested by hand by women and carried up to the road with a heavy basket on their back and uncomfortable-looking wooden board to give crude support to their backs. In another valley pineapples, women selling pineapples at one yuan apiece, less than ten pence, dried mango for eight yuan per half kilogram. Everywhere there were watermelons, on sale for one yuan per kilo. Such roadside stalls and sale of farm produce were not to be seen in Laos, except for the markets in town, and are relatively new to China. In 1978 with agricultural reform families could sell any surplus at rural free markets once they had met the government quota, a percentage of their produce. In 1984 the quota system was done away with to encourage the peasants to produce more by selling all their produce on the free markets.

Jinghong described in the Xishuangbanna tourist map as a ‘city proper’ certainly did not disappoint. A vast new bridge that was still under construction spanned the Mekong, giving access to Jinghong on the river’s West Bank. This bridge, which dwarfs the old bridge one kilometre further north, must be one of the largest bridges that spans the Mekong, and is certainly the biggest bridge that we have crossed.

The city itself is undergoing a major overhaul. Besieged by scaffolding, construction on every corner, it must have been totally transformed within the last couple of years. In spite of the fact that much of the city is like a work site it is a pleasant city, especially so by Chinese standards. By day it has a laid-back almost Mediterranean feel to it with palm trees lining wide, spacious roads, traffic drifting and not rushing. At night the air is balmy and the glitter of neon transforms the city into a Chinese Las Vegas. What really distinguished Jinghong for me is that it is well planned, unlike Mengla where young palm trees have been planted too close to buildings with little thought for the future and the fact that these palm trees will grow.

The city’s people are affluent, smart and well dressed. Platform shoes seem to be in vogue for the women. The men still have the bizarre habit of leaving the makers label on their jacket sleeve as a symbol of status. Mobile phones a necessary accessory for both sexes. A fast food bar selling fruit shakes is full of young trendy girls with little back-packs slung casually over their shoulders, slurping noodles, sipping straws and chatting on the mobile. And if they are worried that they have eaten too much then outside there is a set of talking scales that loudly beckons in a metallic voice, ‘Guanyin, guanyin’, ‘Welcome’. But obesity is not a Chinese problem, although the ‘Little Emperors’ of today's one child policy, who gorge on western fast food and are spoilt by parents and grandparents alike, are prone to the putting on of pounds. On our return to this country I was struck by the size of people in comparison to the Chinese and I am sure that if I had gone to the USA where 50% of the population is said to be overweight I would be horrified.

Legs are very much in evidence, skirts short, one girl in lycra, another in tight shorts and leather boots that of course have platforms. But as Adrian Abbotts points out in his book ‘Naked Spirits’ nobody looks. “What surprised us was not the waxy acreage of thigh on display, but the fact that no man ever looked.” Adrian Abbotts argues that “no man looks because no man knows he should” because of Confucian strictness and prudishness which believed that “a castrated people are a powerless people” and thus for two millennia certain subjects were taboo.

As we watched couples walking dreamily arm in arm, hand in hand, I was suddenly aware of the relaxation in social mores that had taken place. During the Cultural revolution there were attempts to ban kissing on the grounds that it spread hepatitis and couples were not allowed to make contact whilst dancing, like some archaic British public school rule. In 1995 travelling around China I saw no physical contact between couples of the opposite sex, but would often see men walking hand in hand, friends not homosexuals. In 1996 a few daring couples could be seen holding hands on the street, but little more in the way of public displays of affection. Three years on China was embraced in a fondling frenzy like the rest of the western world. From no contact to no inhibitions.

Dazzled by the bright lights of the city we foolishly allowed ourselves to become embroiled in a succession of ‘gan bei’ literally meaning empty (gan) glass (bei). We had generously been invited to join a table of four, two young women and two men, in a small basic restaurant where we had just eaten. More food was offered, “Chir, chir”, eat, eat, as they placed some chicken’s feet and pig’s throat before us. “Women bao le”, “We are full”, was our excuse that only managed to buy us time before we could refuse no longer and opted for the pig’s throat as the more physically acceptable of the two dishes. Their hospitality was not just limited to food as cigarette after cigarette was offered despite protests of “Bu chao yan” and so much so that I began accumulating a small pile of cigarettes.

At one stage we made an attempt to leave, but some of their friends had just arrived and for us to leave now would mean a loss of face to our hosts. We were cajoled and forced into staying. The newcomers quickly took up the challenge of “gan bei”, toasting us with gusto. I thought this version of tag-team drinking most unfair, as they were not bloated with warm, fizzy Chinese beer as we were. This argument held no sway with them, nor did my pleas of “he man” drink slowly. Suffice to say that night soon lost any sense of perspective, so much so that in the early hours of the morning we were singing karaoke. A first and hopefully a last for me.

*

A filling breakfast of ‘jaozi’, dumplings, and ‘xifan’, a watery rice porridge that needs a touch of sugar to save it from blandness and that grows on you in time spent in China with little else on offer, barely soaked up the excesses of last night. We might have saved face last night, doing England proud, but it did little for my head this morning. As we cycled out of Jinghong I was thankful for the easy-going pace of the city and appreciative of its small amount of traffic. The slow pedicabs with their drivers wearing orange jackets that made them look like LIFFE traders in the City. I was also tempted to take one bank up on its very kind offer: it was called the “Help Self of Bank”. In China there are some great Chinglish signs such as ‘Do not stroke the works’ in a museum, ‘No smoking in Pubic Places’ in one set of hotel rule. And my personal favourite is ‘BusyMum Centre’ rather than business centre. In our hotel in Menglun there was one room that made the mind boggle, ‘The Room of Sorrowless Flow’.

Overnight many of the streets of Jinghong have been transformed. Yesterday dirt roads, today tarred; last night no pavement, this morning a pavement. And all a result of the gangs of workers busy throughout the night, tapping, cementing, paving and digging, and all by hand, without equipment such as pneumatic drills. The amount they have achieved is impressive, though one must question the quality of the workmanship. China has a great propensity to build quickly, to build for the short-term without regard for the long-term. It is uncertain whether such buildings will stand up to the next few years, let alone the test of time. But the workforce of Jinghong is driven by a deadline, a seemingly unrealistic one of May 1st when a worldwide horticultural exposition opens in Kunming for six months. The plan is to have all the construction in Jinghong finished by this date, a little over a month away, in expectation of the massive increase in tourism and visitors to Jinghong as a result of the expo. An ambitious plan and one that takes for granted that the expected influx of visitors will justify the cost of this phenomenal construction project. There are those who doubt that this construction will be worth it.

The 111 kilometre cycle to Mengman was tiring, in part a hangover of the drinking last night, but largely due to the climb that we had to endure. Not even the impressive scenery of the terracing could detract from the sweat in the eyes, aching knees and confoundedly sore backside. En route there were two moments of light relief. One was watching ten Dai women, tea pickers, squabbling and arguing with one very harassed man over how much he was paying them for what they had picked. He carefully tried to weigh and note the amount that each woman had picked and remunerate them accordingly. Yet the women were wary, unhappy that they had not been given enough money, gabbling in their Dai dialect, the numbers of which sounded very similar to Laotian.

The other moment was the Octagon temple at Jingzheng. It was not the temple itself that fascinated but a grim and grotesque collage that depicted with a graphic garishness the treatment dealt out to sinners at judgement. Those intoxicated by alcohol had water poured down their throat until they drowned - I looked nervously over my shoulder to ensure that a similar fate was not about to befall me. Those lying or telling untruths had their tongues pulled out with tongs or pecked out by a raven, whereas others were hung on a line by their tongues. Those who had stolen had their hands chopped off, relatively humane compared to some of the other punishments. Those foolish enough to commit adultery had to climb a tree of nails naked and then suffer the indignity of being poked in painful places with a pitchfork. Such scenes altered my perspective on sinning and made me realise that my present discomforts as a result of a bicycle saddle were nothing in comparison to what these lost souls were suffering.

The incredulous looks on people’s faces as we eventually cycled into Mengman were clear evidence that foreigners, and especially those crazy enough to cycle, were not a common sight - we later found out that only two foreigners had passed through here last year. Wide-eyed and open-mouthed the hill-tribes women could not believe their eyes and gawked in curious fascination. We were equally intrigued by them and their colourful dress and wonderful head-dresses, but in terms of staring they won hands down.

Mengman is a small town with little to recommend it, merely acting as a drink-food-toilet stop for weary bus travellers. For those unfortunate enough to breakdown or be cycling it is a stopover. The grim building that was our ‘hotel’ was basic and simple. Our room consisted of two beds and a concrete floor, the shower being a spluttering tap that was at head height at one end of the corridor. But at least it was a bed for the night and its drabness was more than made up for by the friendliness of the family running the building. They brought us tea, made sure that our bikes were securely locked up and then fed us like kings, chasing the local madman away so that we were left to eat in peace. Always helpful and always smiling it is the generosity of such people that makes travel so worthwhile and one able to endure the lack of creature comforts.

*

Eventually sleep saved me from the loud blaring music. But unfortunately in the morning the noise was still beating out with two stalls on opposite sides of the road trying to out-volume each other, pandering to the Chinese taste of all things high in volume, having no consideration for the more sensitive ears of foreigners. The only relief from such deafening decibels was to breakfast quickly and get on the road. And that is exactly what we did.

Just six kilometres done the road, one of the bolts holding my front rack together sheared, in similar fashion to Ian’s. I tried to patch it up with gaffer tape, hoping that this would hold out until Lancang some fifty-five kilometres away, but the road did not help matters. The road deteriorated into a bumpy, pot-holed dirt track that played havoc with the bike. Juddering and banging, jolting and jarring, it did little to appease raw buttocks, aching thighs and fraying tempers. As the road worsened so too did the state of my rack until I was reduced to carrying my right-hand front pannier on my back rack. To make matters worse it was all uphill, a slow painful struggle in which we had to battle to gain purchase and momentum in the loose sand.

Weary, exhausted and downcast we limped into Lancang and sought comfort in the ‘best hotel’; in town, the Xiao Quan hotel, which at 60 yuan a night did our laundry free of charge and had blissfully hot water. But before I could enjoy such luxuries, I had to see if I could get my rack fixed, or at the very least try to salvage what remained of it. I was dubious of success, as back in London a number of bike shops had been unable to fit the rack in the first place due to the angle of the Kona Caldera’s front forks.

A bicycle mechanic squatting by an inner tube, hands blackened by years of oil, looked cursorily up as I wheeled my bike towards him. My limited Chinese was just able to ask him if he could fix my rack. A brusque nod was indication that he would give it a go. As he worked a small crowd, intrigued by the bike and the distance that we had cycled surrounded me. “Zhende,” they exclaimed in disbelief at the distance that we had covered.But if they were impressed it paled in comparison to my admiration for the bicycle repair man who took the rack apart, beat it back into shape and then managed to screw and bolt it all back into place. “Duo shao qian?” I enquired, but he dismissed my offer of money with a wave of his hand. No matter how much I tried to insist that he took some money, he was adamant in his refusal, not accepting anything. Considering the difficulty of the job, its importance to me and the rest of our trip, and that he knew the value of the bike (it had been one of the many questions from the assembled crowd), it was an incredibly generous gesture.

Spirits buoyed by my new improved rack, Ian and I went off in search of food. “Nimen qi zi xing che?” asked a well-dressed man. “Dui,” I replied. This man had seen us earlier in the morning at Mengman and was impressed that we had reached Lancang in one day and had stopped to tell us as much. It was kind of the man to stop and flattering to be recognised, perhaps not so difficult as we had seen no foreigners since leaving Jinghong a couple of days ago. Feeling better still we decided to celebrate with a beer, after all it was Saturday night.

Bladder full of beer, it was time to go to the loo. “Ce suo zai nar?” I asked in the small restaurant where we had been eating. I was led into the darkened kitchen. A dim light was switched on revealing that there was no other door out of this room, where was I expected to pee? The woman went over to the far wall, untied some string and opened a small wooden window and pointed. I stepped cautiously out on to a wooden gangplank. “Zher?” (here) I queried in horror. She ruefully shook her head and pointed further out into the darkness. I felt my way forward until in the darkness I could just make out the Chinese character for toilet, to my relief.

*

We had breakfast, ‘xifan’ and ‘youtiao’, doughy breadsticks, on the street watching the barter and bargain of the Sunday morning market. Several times we were approached by beggars and each time they were Lixiu women. Each time the woman in charge of the stall chased them away, chiding them for hassling ‘waiguo ren’, us, the foreigners. Previously I had seen little begging in China, only in the big cities such as Beijing and Xian where there are plenty of tourists, but here in Lancang it seemed commonplace and presumably a result of disparities in income and lack of potential earning power. Inevitably the poor in this area are non-Han, minorities who do not have the ‘guanxi’, connections, that the Han do. The predominance of the Han effects every aspect of Chinese culture and society, even to the extent that it has infiltrated the language: many refer to themselves not as ‘Zhongguo ren’, Chinese people, but as ‘Hanzu ren’, Han people.

The market itself was a hive of activity, a welcome relief from depressing thoughts of beggars, poverty and the collapse of the sense of community. Vegetables were studiously weighed in ancient hand-held scales. The actions of the vendor scrutinised with suspicion by the cautious buyer. There was a healthy variety and assortment of vegetables, all sorts of different gourds and cucumbers, purple piles of aubergines, red ripe tomatoes. Fruit, gigantic watermelons, bags of chilli, rows of roots all clamoured for space. Chickens squawked lethargically in cane cages. One chicken escaped the clutches of its owner and as its legs were not tied close enough together, it managed to hop and scurry away much to the delight of those around. One alarmed owner in green Mao jacket and blue Mao cap took chase immediately, pushing and shoving through the laughing crowds, his weathered face grim with determination, until the chicken was safely back in his arms. Dogs on leashes yapped angrily at passers-by, owners trying to groom their cats to make them look more presentable and hence fetch a better price.

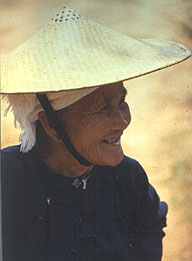

There were plastic goods, bright Tupperware brought to everyone’s attention by the ear-splitting sales-pitch of a sharp, young salesman into a tinny megaphone. Shoes, cheap and plastic, the ubiquitous platforms were spread out on plastic sheeting. Old men sat silently by piles of medicinal herbs, wistfully stroking their whiskers, or rustling through the pockets of their ancient and worn Mao suits, still unused to the concept of a market, the idea of hard sell. The old looked lost and out of place in their uniform of yesteryear. The scene was dominated by the clothes of today, snappily dressed men in their suits, labels proudly displayed on the sleeve, women jaunty in their high heels and lycra leggings.

I would have loved to stay longer, engrossed in people watching, noticing mannerisms and idiosyncrasies, observing heated discussions and watching families go about their weekly shop in a much more colourful and individual environment than our soulless supermarkets. But we had ground to cover and so cycled off. As we left town we passed streams of people all heading for town, for a big day out, some walking, others crammed into the back of a small well-used tractor.

The first two hours of the morning were spent in laborious ascent of what seemed like yet another mountain. The gradient was steep, the drop from the edge of the road was stunning, but more impressive was the fact that it was actually farmed. For as Ian said, “It is a challenge to get down there, let alone working on the land and getting it to yield produce.” After lunch and a paltry thirty kilometres due to the steepness of the climb, we clattered on to cobbles and spent the rest of the day shaking. Shaking not just from the vibrations of cycling over cobbles, but shaking our heads in disbelief that things could get worse, that there was still more pain and hurt to endure. And suffer we did, so much so that by six o'clock within sight of what we hoped to be the top of the pass we were so fatigued and light-headed from exertion that we could not continue.

Fu Ban had little to offer in the way of accommodation and even less to offer in the way of food, a reflection more upon its inaccessibility at the top of this mountain pass than of the hospitality of the villagers. We were presented with pot noodles, biscuits and sprite, not the most inviting of meals but, given our weariness and depleted energy levels, very welcome. Worn out and lethargic I did not have the energy to deal with a puncture, it was straight to sleep.

*

A strange incomprehensible dialect is a traveller's nightmare and not a situation that I faced with equanimity that morning. We were both hungry, still starving form yesterday, and yet I could not get myself understood. Every question, every request for food, was met with a blank stare. There was no option but to flap my arms and make clucking noises, my world-famous chicken impression. Thankfully it worked and we were soon slurping our way through noodles and a sort of scrambled egg, feeling better already.

Puncture repaired, back tyre changed, and after a short climb to the top of the pass, we were able to enjoy the luxury of downhill. The scenery was quite simply stunning, a series of terraced steps all the way up the mountainside. What in any other country would be un-farmable land had been transformed into productive terraces. Some just harvested, a muddy brown, others a bright green, ripe for the picking. The whole hillside a variety of hues, giving it the effect of a patchwork quilt. In some terraces the women were harvesting the rice, ankle deep in a quagmire of mud, dressed in colourful jackets and wide-brim hats of cheap quality. Their backs bent at uncomfortable angles, legs straight, in lines of three or five or six they would inch forward, not missing anything, the picked crop lying neatly to one side in little bundles. The men, meanwhile, were coaxing cattle or water buffalo under the plough, digging up the terrace in readiness for the next crop, or tending to the terrace walls, either fastidiously repairing or breaching a wall to drain the terrace and thus flood the one below. Everywhere there was industry, either maintenance or harvest, ploughing or picking. The quiet labour of farm-work broken only by occasionally by a farmer clicking encouragement, urging his beast of burden to greater effort with the plough.

Our enjoyment of this bucolic work, the toil of the peasant farmer that has remained unchanged for hundreds of years, the knowledge of farm that has been passed down through generations, did not last long. A series of mishaps struck. First my rack sheared again, meaning that my right hand pannier once again had to be strapped to my rear rack. Worse was to follow when Ian's rack gave in completely and had to be discarded. This meant that he had to cycle with both panniers strapped to the back of his bike, making handling difficult and ascents even more arduous. Progress was thus slow as we tried to nurse our wounded bikes across this temperamental terrain.

Eventually we reached the valley floor and began to follow the passage of a river upstream, but thankfully the incline was gentle and the gradient never got the better of us. The river itself had a pungent odour, the off-putting smell of rotten fruit, old cabbages and sewage all in one. It did not look much better, its water the black of a dead river, a river lacking life. A duck-herder, tending to his flock of ducks, clucking and calling them to order, berating the strays, seemed oblivious to the foulness that was around him. Two thoughts crossed my mind. Firstly that I am not eating duck in this area after they have been living in such unpleasant water and secondly that why did they not fly away? Have these ducks had their wings clipped or are Chinese ducks so domesticated that they have lost the ability to fly, to escape the cook’s knife?

The lifeless river waters seemed to pervade the valley with a foreboding of death. The sun was merciless, vegetation scant, village life absent, traffic a desultory trickle. Worse still there was no sign of a stall, the welcome wetness of a drinks’ vendor. The air was sterile in this Chinese equivalent of Death Valley. Parched we peddled on preferring thirst to drinking the water of the river, albeit after it has been through our water pump. Twenty-six kilometres from ShuangJiang we came across a ‘drink stop’ and probably doubled the woman's weekly sales as well as causing much amusement by our thirst: we drank four cans of fizzy drink and seven bottles of water between us.

Some 106 kilometres and much sweat later we struggled in to ShuangJiang. Hot, dirty and sweaty, hot water and a good wash were paramount in our minds, so we asked a policewoman directions to a ‘binguan’, posh hotel. This officious policewoman obviously thought that we, two cyclists who had navigated our way through three countries, would not be able to find the hotel by ourselves and escorted us all the way there. For this we were grateful but once at the hotel she did not believe that her usefulness was at an end and began filling in the standard hotel registration forms for us. Here she was more of a hindrance than help, doing everything by the book and frustrating us by the amount of time that she took to do this otherwise straightforward process. Forms finally filled in, the policewoman thanked, the room disappointed in its lack of our primary requirement: hot water. After angry protest it appeared that there was no hot water despite earlier assurances and promises - typical of the problems that one faces whilst travelling in rural China and usually one accepts it with a pinch of salt, but not today. Not to be defeated, I persuaded our ‘attendant’ to bring us a number of flasks and kettles of hot water so that we could at least bathe in lukewarm water. In doing so we managed to cleanse ourselves of sweat and dust and perhaps reinforced the view amongst the Chinese that foreigners are truculent and difficult.

*

A late rise at eight o’clock, a bit of bike maintenance, cleaning chains, checking bolts and oiling, and we freewheeled into the centre of town for breakfast on the street. Breakfast consisted of ‘cai bao’, literally vegetable bread, fried and so good that we had several each, as well as a couple of oranges. The food was great, the situ not so, as we were eating by a drain watched by hordes of fascinated Chinese. Staring is a national pastime, and I fear that on my return to England I might be equally affected and stare at everybody, and no doubt get myself into trouble, “Oi, wot are ya looking at!” In England we value our privacy and space, and are consequently much more aggressive. But in China staring invades such boundaries and as a ‘lao wei’, foreigner, we are an open target, especially in these parts where we are a far from common sight.

If I have dwelt on the mundanities of travel in China, the minor eventualities, then please forgive me. But this is what makes China fascinating and travel in it so exasperating at times and yet so rewarding at others, for instance when you make a connection with the local people. There is also the fact that we are travelling through very rural China, so off the beaten track that there is little party influence let alone foreign influence in these parts. There is little else to describe other than the way of life in the countryside, the stunning terraces, the amount and variety of crops grown from sugar cane to rape, from tea to rubber. Also, because of the mountainous terrain, our energy is often sapped and the scenery unfortunately blurs and blends into a sweaty haze.

Today I saw a child with only a T-shirt. At first glance an unremarkable sight, but on further thought, I realised that this was the first sign of abject poverty that I have seen in China. In Laos there are semi-naked children everywhere, such poverty and hardship being more commonplace. In China there is certainly hardship, the life of the peasant farmer is far from easy, but they work harder and make better use of the land and hence are a little better off.

Inevitably today’s cycle involved a struggle up a winding series of hairpin bends, with stunning views of waterlogged terraces and dust filled eyes and mouths as trucks roared past. After several hours climb and still some six kilometres short of the summit, a kindly county official offered us watermelon. Yet more Chinese generosity that cannot be reciprocated and further evidence of the ubiquitousness of watermelon. Eventually we reached the summit, and began a slow and painstaking descent. Unfortunately due to the late start and the height that we had to climb over the pass we were unable to reach our target of Lincang, falling short by 42 kilometres in the small truck-stop town of Dougou.

Here we were directed to the only building bearing any semblance to a ‘luguan’, basic hotel, or in this case a truckers motel, a two storey brick building with three Spartan rooms upstairs and a ‘dining area’ downstairs. A bargain for 14 Yuan a night for a double room consisting of concrete floor, window, door and two beds with blankets that had seen better days. Two stools and two buckets were put out in the backyard for us to wash alongside the chickens.

Having washed we came down to the dining area, a bare concrete floor given spice by five wooden tables, surrounded by stools, and a typically loud TV in the corner. The television was a focal point during the evening, people drifting in and out to view snippets of a world not accessible to them, a world of soap-opera riches and drama. Yet this world of glamour and drama was viewed with ardent interest, and at times with amusement at the banality of life featured. I am sure that those watching, clutching their jars of tea, felt that if those in the soap think that they have to cope with drama and hardship, then come and experience the real life here in Dugou.

*

An early morning call of nature sent me scuttling off to the village toilet. Early morning is probably the best time to face such horrors, before the heat of the day makes the stench unbearable. (Night is probably the best time to go, as you cannot see what litters the floor, but then you have to worry about your footing). To say that this toilet was disgusting is putting it mildly. A low concrete trough clogged up with urine and spit, papers and straw, against one wall. Opposite it, against the other wall, three holes in the ground, each divided by a foot high partition. Loo roll, faeces, newspaper and fag ends were strewn across the floor - it amazed me that anybody could read a paper or enjoy a cigarette surrounded by such a sight and whilst the nasal passages were being assaulted by the pungent stench. But then the Chinese must have different sensibilities to me for such a toilet is typical. It never seems to amaze me that despite the fact that China has so much and that over the centuries it has given so much to the rest of the world, from gunpowder to the compass, from the stern-post rudder to the kite, from the printing press to tea to silk, it cannot sort out its toilet. (Whilst I am on my high horse of complaints about China, the fact that they do not queue rankles and again surprises in a country with such a large population and in which order is so valued, that they lack discipline and patience and resort to pushing and shoving).

Anyway, back to my squatting, where I was trying to mind my own business, forget my surrounds and be out of there as quickly as possible. Well that was until a busload of school kids, dressed in their uniform blue tracksuits and red scarves, pulled outside and descended upon the toilet. The excited chatter and hurried footsteps of bursting school children was suddenly halted as they stared incredulous at an equally startled me. A second later they overcame their surprise and shyness and began practising their one word of English, ‘hello’, over and over again. What else could I do but grin and bear this humiliation, smile politely back as if nothing was out of the ordinary and hope that an impatient bus driver would beep his horn, summoning the children back to the bus and leaving me in peace. I think it is fair to say that I was well and truly ‘caught with my pants down’.

I managed to escape the toilet without further ado, without further loss of dignity, and was glad to be on my bike and out of there. Shortly after our departure the bus passed us, the kids waving and smiling, expressing the intimacy of our relationship, the shared bond of toilet. I am glad to say that the rest of the forty-two kilometres to Lincang passed without event. Not even the state of the road or the amount of construction on the edges of Lincang, typically Chinese in its ambition, could phase me after that early morning experience.

The Golden Origin, our hotel for the night, had a smart glass front and festive flags proclaiming prosperity, which made the hotel look like a used-car-sale lot. The neon announcing that the hotel had KTV, the helpful staff purposefully trained to be of service, symbolising the aspirations of China, its future and potential. On the opposite side of the road is a cafe, in which I am sitting, that is bare and in need of a white-wash, with bones and tissues scattered over the concrete floor. Noodles are being noisily slurped by hungry men in ill-fitting jackets and the carefree cheeky chatter of the cook comes from within the kitchen. This cafe represents the China of today. Whereas the large black pigs snuffling slowly along the road that separates the hotel and the cafe stands for rural China, emphasising the divide between rich and poor, the difference between town and country that is the dichotomy of China.

*

Today was a day spent waiting to catch the overnight sleeper to Kunming. We were making this diversion to Kunming in order to pick up some warmer kit that had been sent via DHL to Kunming and hopefully to see if we could get our racks replaced or fixed. We intended to return in a couple of days. What better way to spend the day than by wandering around the market?

A cacophony of noise, squealing pigs, squawking chickens, sighing men, screeching saleswomen, the slosh of slops and water, the splash of blood, the screaming of babies, the silence of cucumbers. The chickens had good reason to squawk as they were prodded and poked by prospective buyers. Hung upside down, the chickens were continually weighed and passed around for a second opinion, discarded and then picked up again in a moment of indecision. Their life was far from settled and there was much to complain about, but at least they would leave the market alive, others were not so lucky. The less fortunate chickens, were hung upside down in bunches on the outside of large cane baskets, feet tied tightly together, to await their fate: a sharp cleaver to the throat, being thrown unceremoniously into the basket and left to bleed to death in a flapping and flurry of feathers. Once dead, or sufficiently limp and lifeless to be as good as, the chickens were plucked from the basket and plopped into a large cauldron of boiling water. A minute later they were retrieved, bedraggled and dead, with tongs and quickly removed of all their feathers. It was a messy business with congealed blood covering the baskets and pools of blood coagulating on the floor. Waterlogged feathers stuck to everything. It was typically Chinese in that it was in your face and not hidden from view, very different from our sanitised packages of chicken that we buy in the supermarket.

Then there were the meat-sellers, mainly women. Large red sun umbrellas protecting them and their pigs’ tails, trotters, chicken’s feet, livers, entrails, tripe and mounds of fat from the withering rays of the sun. Surprisingly the smell was not strong and perhaps as a result there were no, or very few, flies. Despite there being no smell, all this blood and gore turned my delicate western stomach, but had little effect on the women who busily tried to fill their stomachs with swiftly slurped noodles.

The vegetable vendors were more forgiving, quieter and less of a sensory assault. Wonderful and exotic varieties of mushroom and fungi, wobbling piles of dofu, neat rows of onions, spinach and broccoli. Weirdly shaped gourds, obviously grown naturally and not forced into a standard, conformist shape by a Brussels bureaucrat. Knobbly roots of ginger, the red of tomatoes, bamboo shoots and lotus roots and amongst it all a baby asleep in a basket full of cabbages, oblivious to the chaos around.

This was the market of necessity, of food and produce, of daily requirements. A market of bustle and hustle, that was thriving and competing, heaving and alive with the banter of barter, crowded with pedicabs trying to squeeze through impossible places. The market higher on the hill was that of clothes, toys and other such luxury good and thus was empty, lacking the character of the market below. Few could afford this world of high prices, the world of dartboards, panty hose, 50-yuan cuddly toys and mini pool tables. Or maybe the people of Lincang had taste and were more discerning, not wanting a photocopied poster of David Beckham, a toy gun or a pair of lurid, loud flip-flops that read ‘Camada’ rather than the North American country.

Later that day, as we waited to board the sleeper bus I thought that there was little way that the calligraphy giving the bus’s capacity as 41 could be right. “There is no way that they can fit forty-one people on that bus.” “I hope you are right,” replied a doubtful Ian. But it was me who lost face and not the Chinese. There were four double bunks on each side of the bus, separated by a narrow aisle that was difficult to negotiate at the outset of the journey and that by the end was distinctly hazardous due to the combination of luggage, shoes, watermelon seeds, plastic bags and spit. Thus there were sixteen squeezed into bunks on each side, with nine on a couch-bunk at the rear.

The allotted space for each person was hardly generous by Chinese standards, downright mean in the case of my broad shoulders. The look of horror on the face of Gao Feng when he saw that he was going to have to share a bunk with me was almost comical. His wide eyes and open mouth indicated all too clearly that he did not relish the prospect and did not fancy his chances of catching much sleep.

Trying to catch just a wink of sleep was an art

in itself. The wind whistled and howled annoyingly through every conceivable

crack or gap,

a chilling blast piercing my eardrum through a hole in the window left

by an absent latch. Poles rattled and juddered as the bus thundered towards

its destination. Most frustrating was the clanking together of two panes

of glass, a sound that was sleep depriving in its persistence. Add to

this the fact that the bed was six-foot at best and I am six foot two

inches. Lying on my back, catatonic with tension, the only thing that

distracted my mind from the uncomfortable present was the brilliance

of the moon that shone with a whiteness, a dazzling luminescence. Bright

moon, thoughts of astronauts, lying there in this incorrectly named sleeper

bus, had an empathy with astronauts and some idea of what it must be

like to re-enter the earth’s atmosphere.

|

|

|