Justin Wateridge challenges the harsh realities of Ethiopia’s immediate past to present a land that is very different from any other in Africa, a land where the impossible might just be true…

Mention Ethiopia and most people think simply of drought and famine. But there is much more to this land of contrasts and extremes than starving children and Live Aid. What Ethiopia should best be known for is not its recent tragic history, but its long and rich historical past that has created a country like no other in Africa, a country that is quite simply different

Ethiopia is old; old beyond imagination. Take for example Lucy, the ‘first human’, a 3.5 million year old hominid skeleton that has helped answer a number of questions that have puzzled paleoanthropologists about our past. Ethiopians are rightly proud of Lucy and the longevity of their history – they call her Dinkinesh, which means ‘Thou Art Wonderful’ whereas we call her Lucy after the Beatles song, which was a hit at the time of her excavation.

Unfortunately, apart from Lucy I did not think much of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s modern capital. Although Addis Ababa means ‘New Flower’ there is little new or flowering about the city as evidenced by the ‘Mercato’. The Mercato, one of the largest open markets in the world, is a hotbed of crime and certainly not for shrinking violets – the FCO advice that ‘theft is common’ is British diplomacy at its understated best. This being the case I caught the first plane out of town, a twin otter de Haviland, and headed for the sleepy lakeside town of Bahhar Dar.

Situated on the southern shore of the fabled Lake Tana, Bahar Dar and its sleepy atmosphere were a welcome relief from the crowds of Addis. Here at last, I met the real Ethiopia. Strolling around, dining in quaint local restaurants and trying tella, the local beer, I talked to Ethiopians who were proud and confident (Ethiopia is the only country on the continent that has never been colonised) while at the same time generous and hospitable.

Their hospitality manifests itself in a number of ways, most usually in invitations to drink coffee. Drinking coffee is a national pastime - this is perhaps unsurprising as coffee originates from Ethiopia and is said to be named after the province Kaffa in the southwest of the country – and involves an elaborate ceremony. As I was to find out in one home, the quick cuppa is an alien concept to Ethiopians. The pine needles scattered on the stone floor filled the room with a fragrant freshness, as an old woman sat on a low stool behind a charcoal brazier roasting some green coffee beans in a battered old pan, shaking them occasionally. When the beans were sufficiently roasted she passed the pan teasingly under my nose filling my nostrils with the rich aroma of the beans before disappearing into the next door room. After a good deal of pounding, she returned with a coffee-pot and some handless cups. I had a sense of déjà vu or perhaps advertising is ore powerful than I thought. Whatever, the coffee was great if a little strong.

Aside from its laid back charm and people, Bahar Dar has two main attractions, the Blue Nile Falls and Lake Tana, the source of the Blue Nile. The Blue Nile Falls, four hundred metres in width when in full flood, were impressive and warranted their local name Tis Isat, which means ‘Smoke Fire’ falls. But for me a waterfall is a waterfall and the attraction of the Blue Nile Falls was more than rivalled by the 37 islands scattered about on the 3,000 square kilometre surface of Ethiopia’s largest body of water, Lake Tana.

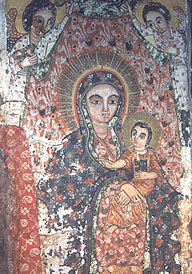

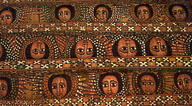

These islands are home not only to an abundance of birdlife but also to many ancient monasteries and churches of immense historical and cultural interest. Ethiopia converted to Christianity in the 4th Century AD and is a land of 15,000 churches in which religion and its art has permeated much of the country’s culture. Many of the churches date back to the sixteenth century and seem to have changed little since then, the church paintings and the illustrated manuscripts having lost little of their former colour and glory.

I had read that many of Lake Tana’s churches were difficult to get to – in fact women are forbidden from touching foot in most of them – but I did not realise quite how difficult until I was down at the lakeside. There for the first time I saw the tankwa, the peculiarly Ethiopian papyrus boat that has plied the waters of the lake for centuries. I use the term boat in the loosest possible sense for in effect they were little more than rafts of papyrus lashed together that were open at the back and looked dangerously unsafe on water. My desire to go to church – never great at the best of times – wavered.

In spite of my better judgement I soon found myself aboard a tankwa and being rowed away from the safety of the bank towards Ura Kidane Mehret, one of the few churches that can be visited by women. Thankfully the tankwa was more stable than it looked but this was little consolation and I still felt remarkably vulnerable, especially when the boatman pointed out some hippopotami in the distance. Back in the safety of my own home it is easy to be full of bravado and say that getting to Ura Kidane Mehret by tankwa was all part of the experience but at the time and knowing that the hippo is reputedly the most dangerous animal in Africa, I was far less certain. To say that I was relieved to get back onto terra firma was an understatement.

Ura Kidane Mehret was very different from any other church that I had seen. As with most of the churches in Ethiopia it had not been influenced by nineteenth century missionaries or modern day evangelists and thus was wonderfully distinct and uniquely Ethiopian. Its conical thatched roof housed a vivid and colourful series of frescoes that depicted graphic scenes of biblical lore. There was a childlike naivety to many of the paintings, a quiet simplicity that I was to find in most of the churches that I visited.

The next day as we were flying over the Lake Tana en route to Gondar the pilot turned to me and asked, “Would you like to get closer to the islands and take some photos of the monasteries?”

“I would love to,” I said gratefully, surprised that this was possible on a scheduled flight.

“Your guide can tell you all about their history,” he said referring to the Ethiopian gentleman seated next to me.

“My guide?” I queried

The pilot turned to the man next to me and asked, “Aren’t you a guide?”

“No. I am an airline safety inspector.” The pilot looked horrified and needless to say I did not get my aerial shots of the monasteries.

Arriving in Gondar was like going back in time. The steep cobbled streets were a melee of ox and carts competing for right of way amongst mules heavily laden with goods from the market. Young boys carrying sticks twice their size tried to coax their cattle back to their homes. Most of the people were dressed in traditional white, homespun cotton.

But it was Gondar’s castles that really took me back to a bygone era and graced the town with a romance worthy of its evocative epithet, ‘Camelot of Africa’. A beguiling mix of Portuguese, Indian and Arabian architecture, the castles, despite the pillaging of nineteenth century dervishes and British bombing in World War II, have retained sufficient of their monuments to give a tantalising picture of their former glories. I was charmed by their eerie silence and further enchanted by Ethiopia and its past.

Most intriguing of all must be Lalibela, in name if nothing else. Named after the twelfth century king who tried to recreate a New Jerusalem there, Lalibela means ‘the bees recognise his sovereignty’. Still trying to come to terms with what this meant, I was shocked out of my reverie by Lalibela’s eleven rock-hewn churches. These subterranean churches are literally carved from the solid rock, both outside and inside, and were staggering in their size and complexity. Stories abound as to how they were completed, from gangs of slaves to angels to the knights Templar, but whatever their origins they are a truly remarkable feat and worthy of UNESCO’s title of Eighth Wonder of the World.

I spent a whole day negotiating the bewildering labyrinth of tunnels and narrow passageways that were offset with crypts, grottoes and tiny prayer holes into which were crammed hermit monks. The churches themselves were dark and atmospheric with the chanting of Giez, the ancient language of the church, and the deep throb of the kebero, a large oval drum, resonating loudly. As I felt my way along stone walls worn and polished from use over the years, I could not help thinking that little had changed over the centuries. That is except for the camera touting tourists who asked the priests of the churches to stand in the sunlight displaying gold crosses and other church treasures - I am not so sure if the Archbishop of Canterbury would have been so obliging.

Seeing so many churches was thirsty work and I sought solace in tej, a local mead made from honey. As I was pondering this further connection with bees, I foolishly tried some injera and wot, the national dish of Ethiopia. I have never tasted anything quite like it and frankly do not want to again. The wot was a spicy concoction of meat and vegetables that was so fiery and peppery that to cool my mouth down I tore off and began to chew a bit of injera, a fermented pancake-like bread that looked like carpet underlay. Made from water and teff, a locally grown grain, it tasted no better than it looked and whilst my appetite had been whet by Ethiopia as a whole the same could not be said of Ethiopian food.

Flying to Axum was a treat as the dramatic scenery of the Simien Mountains unfolded below. One of the major mountain massifs in Africa, the Simien Mountains are home to a number of endemic species such as the elusive Simien fox, the Gelada baboon and the nyala. A stunning array of craggy pinnacles and crevices, deep precipices and gorges, the mountains are rugged and challenging trekking country. Better still, the Simiens only receive a handful of visitors every week.

Axum the first great city of Ancient Ethiopia was my last stop. The origins of Axum and its empire remain obscure, shrouded in legend and stories of the Queen of Sheba. However few would query that Axum was one of the most important and technologically advanced civilisations of its time, a major force from the 2nd to the 7th century and one of the four great kingdoms of the world along with Rome, Persia and China.

Today it is an archaeological treasure, which includes the ruins of the Queen of Sheba’s Palace and the underground tomb of King Kaleb. But the focal point of Axum’s archaeological ruins is the stelae park, a remarkable series of giant monoliths carved from slabs of granite. The tallest stelae, now fallen, was over 33 metres high and the largest single piece of stone ever successfully quarried and erected in the ancient world. These stelae are clearly the products of an advanced and prosperous culture, yet no one knows why they were raised or by whom.

The greatest mystery of all, however, concerns

this city’s claim

to be the last resting-place of the Ark of the Covenant. It is a claim

that the Ethiopians have held for over two thousand years, a claim given

form by the fact that there is a tabot, a replica of the Ark, in every

church in Ethiopia. I had had my doubts until I visited the Church of

St Mary of Zion, the resting-place of the Ark, and met one of the guardians

of the church whose gentle yet highly persuasive manner disarmed even

my cynicism. Perhaps it was just the certainty of his faith that gave

me that impression and changed my mind, but I think not, he definitely

seemed to know something that I did not. For me Axum encapsulated much

of the enigmatic charm of Ethiopia and if you still have your doubts

it is time to don the hat and the jacket and find out for yourself.

|

|

|