Can I go down there?” inquired one of the group, peering over the edge.

“You go, I’ll write about it,” was the laconic reply of our Guyanese guide that revealed the immensity of the drop and quickly brought the over-inquisitive group member back from the edge.

At a dizzy seven hundred and forty one feet, the spectacular Kaieteur Falls are immense, the largest single waterfall anywhere in the world. Kaieteur ranks alongside the Niagara, Victoria and Iguazu falls in power and majesty with the added attraction that it is surrounded by virgin forest. In his book ‘Ninety-two days’ Evelyn Waugh described Kaieteur as “one of the finest, most inaccessible and least advertised wonders of the natural world.”

Waugh’s description has stood the test of time as neither the grandeur nor the remoteness of the falls has diminished over the years. Getting to the falls is an experience in itself – either you slog through the dense jungle for several days or you take a stunning flight over the jungle and myriad of rivers in a light aircraft. Whichever you take, the final destination is undoubtedly worth it and arriving at the falls I felt as if I was discovering them for the first time – there were no signs and none of the trappings of tourism that clutter other great natural sights. There were no protective railings and the sudden drop into nothingness sent a cold shiver down my spine.

The sheerness of the drop, the vertiginous height, unsettled me and even slithering forward on my stomach was terrifying. Peering nervously over the edge I watched drops of water fall, fall, fall into empty space. I had expected there to be a thunderous roar of water, not dissimilar to the Victoria Falls (locally known as ‘the smoke that thunders’), but so great was the height of the falls that only at the brink could I hear the muffled sound of water reaching the bottom.

But if you have not heard of Kaieteur Falls, Guyana’s main attraction, then what has the country got to offer you? For as Waugh wrote, “Who in his senses will read, still less buy, a travel book of no scientific value about a place he has no intention of visiting?” To paraphrase Waugh, the answer is that there are hopefully a certain number of people who enjoy the same kinds of things as I do. Thus an experience which for me was worth a month of my time and a great deal of exertion may be worth a few minutes reading to others.

Arriving in Guyana, I was confronted by the poor simplicity of a third world airport building bored by bureaucracy. In contrast to the building the airport staff were colourful and charismatic. The immigration officials were chatty and amiable, asking friendly questions, intrigued as to why we were coming to Guyana. However, I was somewhat unsettled by one question they asked me, “Are ya wid da church?” It seemed to imply that only those on a heavenly mission visited Guyana.

Outside the airport we were consumed by darkness, there being little electricity in Guyana. Other senses heightened to compensate for this lack of sight, I was awash with new and strange sounds and smells. The air had been softened by recent rains and was heavy with the smell of earth, the smell of muddy potatoes. The thick grass that lined the road was singing with the constant siren of cicadas. Occasionally we passed a late night drinking hall from which the big bass of reggae boomed out into the darkness. Arriving at Camp Ceiba, our home on the edge of the jungle for the next two nights, we were faced with the challenge of putting up our hammocks in the dark. As we stumbled and fumbled in the dark we cursed the lack of light and our ineptitude, but were enthralled by everything that lay ahead.

The excitement of our arrival late last night had not worn off, and despite the early hour we were up early, exploring the environs of the camp. The discovery of tortoises, lizards, an enormous frog, a pair of parrots and other exotic birds was met with wide-eyed enthusiasm, which turned to horror when a large pink-footed tarantula was found. Once cameras had been produced, clicked and put away it dawned on the group that the tarantula had been above their heads last night and would more than likely be there for the next night. It was only afterwards that I found out that this type of tarantula is relatively harmless.

Later that day we set off into Georgetown, Guyana’s capital, to explore and buy provisions for the journey ahead. Driving into the city Guyana’s cultural diversity, that it was a melting pot of peoples and cultures, quickly became apparent – for a start our driver, Vishnu, was a Christian. Colourful flags denoted Hindi houses, shoes lined up outside mosques indicated that it was prayer time and towering spires marked the fact that Christianity was the dominant religion. The Church of St George, reputedly the tallest wooden building in the world, was an icon of purity in the otherwise troubled streets of Georgetown. Georgetown is not unsafe; well certainly no more so than any other capital city, but an air of expectation hangs heavy. Young men loitered and stared as stereos were tested to their limit.

I found it difficult to get a feel for the people, partly due to their cultural diversity but primarily due to the fact that they were so difficult to understand. I had asked Aunt Dolly (pronounced ‘Aren’t Door-lie’) what she advised as a good staple food on the trek. “Coup inner tin,” she remarked. “Excuse me?” I replied. “Cow in a tin,” she repeated much more slowly, meaning corned beef. A lot of educated guesswork is invariably involved in any conversation with someone from Georgetown.

The next day we headed into the interior in a Bedford 4-tonner. Such a tried and tested vehicle is a pre-requisite for any such journey – there are only 550 kilometres of tarred road in Guyana, a country the size of the UK. The rest of the roads, and I use the term loosely, are often little more than a single track hemmed in by the encroaching jungle. Rutted and waterlogged, they are impassable for much of the year and the tyre tracks and deep ruts indicated the problems of earlier drivers. Our Bedford whined and discharged diesel at an alarming rate as it slipped and struggled with the surface under tyre. Its efforts were to no avail and not for the first time we had to resort to the winch to rescue us. Travel in the interior of Guyana is invariably a drawn out and protracted process, a real adventure - but it is worth the effort.

Once in the interior we quickly settled into a daily routine and each morning, hammocks and mosquito nets were packed away in the pre-dawn dark. With torch batteries dulled from overuse and eyes blurry with sleep, or rather the lack of it, our preparation for departure was ponderously slow. Invariably the Kabora fly had got the better of me the previous day and I had spent a sleepless night scratching bites. The itch induced by the Kabora bite is maddening in its intensity but thankfully does not last more than a couple of days. No deet or repellent was foul or strong enough to keep the little buggers at bay.

After a breakfast of farine (the Guyanese equivalent of porridge made from cassava), it was out into the jungle, which, despite the humidity and multitude of creepy crawlies, was for me one of the main attractions of Guyana. Although it did not conform to my predetermined stereotypes of snakes slithering through vines and tapirs crashing through the undergrowth, the jungle inspired in me a sense of adventure, a sense of the unknown. The wealth and variety of vegetation, from lianas to lichens, from mushrooms to monkey ladders, never ceased to amaze me.

And yet it was the green, submarine darkness of the jungle that most surprised me and can never be realised until one has been there. Not only did I not appreciate how difficult it was to see, but also how much there was to hear. The jungle was a multitude of sounds, a cacophony that was heard but not seen. It was difficult enough to locate sounds let alone determine what they were. Frogs sounded almost human, insects droned incessantly, humming birds chirped loudly all around us. Straining my ears I heard the distant noise of an aeroplane – the first mechanical sound that I had heard in over a week, which brought home to me the remoteness of the jungle we were trekking through.

Despite the difficulty of spotting wildlife, we did see some, including, perhaps unsurprisingly, the aptly named sloth. It’s head was small, almost absurdly so, its claws long and powerful, as were its arms which seemed to have a sinewy strength beyond its size. The sloth seemed to symbolise Guyana and the sedate pace of life in the interior, where the heat, humidity and blight of insects reduced any movement to a crawl. More than anything the sloth intrigued me as to how it had survived evolution, it seemed to challenge Darwin’s theory of the survival of the fittest.

The sloth was one of the most bizarre animals that we came across, but the most exhilarating moment was the sight a pair of macaws in flight. Their cry was uplifting as they soared above the canopy; their colouring bright, exotic and vibrant against the greens of the jungle. Seeing them flying in unison was a magical moment.

Each day would invariably involve a river crossing – Guyana is not called ‘the land of many waters’ without good reason. An easy crossing would be in a dugout canoe. A moderate crossing would involve fording the river – this in itself was not difficult, but warrants moderate status because of the inherent dangers of piranha and the discomfort of wet feet. A difficult crossing would necessitate negotiating a half-submerged log or worse still a fallen tree with a vine acting as an improvised handrail. Both of these required a sense of balance and foot dexterity that was nigh impossible in walking boots. At the very least, river crossings added a certain sense of drama to the day.

At the end of a hard but rewarding day’s trek we would walk into a clearing in the jungle occupied by a handful of huts that comprised the local village. In one particular village, Tusening, I was offered a gourd full of a welcoming drink of cassava spirit. Not dissimilar to watery porridge, it looked innocuous enough and I was about to take a healthy swig when I noticed a man passed out under a nearby mango tree. For once in my life I showed some restraint.

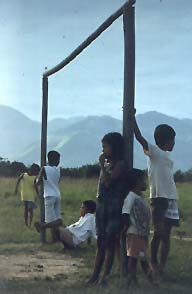

Despite being red-faced, sweaty and out of breath, I was always greeted by warm friendly smiles, welcoming eyes and infectious laughter. The Amerindian villagers were very different form the peoples on the coast, in appearance, style and friendliness. The adults were generous and hospitable to the extreme. The children were less certain at first, staring in bewilderment at us, for few if any westerners (or yellow people as we were referred to) come through this area. Once they had overcome their initial reserve, the children were full of unaffected curiosity and eager for us to go fishing or hunting with them. In one of the less remote villages they even wanted us to play cricket against them.

On one Sunday morning, in a scene that would not have been out of place in the film ‘The Mission’, I found myself seated in church. The timid priest struggled to be heard above the creaking of the corrugated iron roof in the sun, the rustling of children’s feet, the scraping of wooden benches and the dogs barking outside. The humidity was oppressive. The congregation sat patiently fanning themselves. In spite of the sweltering heat everyone was in their Sunday best and looked immaculate. I wondered how they managed to keep everything so clean when the rivers were so swollen with mud.

I was awoken from my reverie by a question from the priest, “Brother Justin have you found God?”

I was not sure whether I had, but I was sure that

Guyana could be one of the destinations of the future. Right now it

is a place for more rugged

and independent minded people who have time and patience, and don’t

mind visiting a country that most people think is in Africa. But in the

future?

|

|

|