The land below me was not how I had imagined it at all. A series of round–shouldered buttes, wave after wave of hills and hillocks that were green, very very green, productive and full of energy. It struck me that before I had even set foot in the country I had been bamboozled by stereotypical press images. My predetermined view of Rwanda was one of genocide and perhaps to a lesser extent gorillas. I had fallen foul of the adage that “the tourist sees what he came to see and the traveller sees what he sees.” Thus as I emerged from the modern airport after a smooth and seamless passage through customs and immigration – further myths laid to rest – I determined to take Rwanda at face value.

Immediately, I was struck by the beauty of the country. It is spectacular to behold and more than worthy of its epithet of the land of a thousand hills, Mille Collines. This landlocked country, half the size of Scotland, is the most densely populated country in Africa and its perfectly rounded hilltops are woven with steeply terraced slopes of banana and plantain. Even the steepest slopes are tilled, shaded only at their summit by a vestigial crown of tall trees. The silvery silhouette of eucalyptus trees stand out against the brilliant green of the tea plantations. Misty, moody rainforest in the south gives rise to lushly forested volcanoes and bamboo in the north, dugout canoes ply the tranquil waters of Lake Kivu in the west and undulating grass plains of Akagera in the east are interspersed with light acacia woodlands.

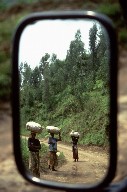

Due to its small size, few journeys are long and arduous in Rwanda rather they are absorbing. The roads teem with people, streams of human traffic, walking many miles to the local market. Multi-coloured umbrellas emblazon. Women in brightly coloured sarongs with their young strapped to their back balance impossibly heavy loads on their heads with grace. Young boys ride ridiculously oversized wooden bicycles. Others struggle to push their bikes uphill laden with bundles of sugar cane or the ubiquitous yellow water containers.

On the rich red earth at the roadside, coffee beans lie on grass mats drying in the sun. Clumsy red bricks are stacked by smoking kilns. Barefoot children tend to goats, pigs and sheep. Sacks of potatoes, bags of charcoal offer visual evidence to the population density and the intensity with which every part of the land is worked.

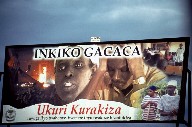

Sadly too there is evidence of the genocide, one of the worst atrocities of the twentieth century in which 800,000 people, a tenth of the population were killed in six weeks. That is a rate of slaughter five times greater than the Nazi concentration camps and hence Rwanda has become synonymous with genocide. In almost every village there is a memorial site to the dead and billboards everywhere announce the next Gacaca, the village court system seeking to bring the perpetrators of the genocide to trial.

Rwanda’s well-documented and grim history cannot be easily ignored. Did I want to see a genocide site? I had the feeble excuse that it was to write this article, to inform others but was that really the case? Was I driven by some perverse fascination? I am ashamed to say that this might have been the case before I visited Nyamata genocide site; it was certainly not afterwards when all I felt was revulsion.

The church in the small village of Nyamata, some twenty bumpy miles south of the capital, Kigali, was the scene of a horrific massacre where some 20,000 were killed in the first few weeks of the genocide. We arrived at a nondescript red brick building and were met by an elderly guardian of the church who quietly relived the horrible events of April 1994. When he had finished I asked in my stilting French ,“Les morts sonts ici?” “Oui la ba,” he replied.

In a courtyard behind the church were several underground chambers in which are stored and displayed the skulls and bones of many of the victims. Row upon row of hollow skulls stared lifelessly back at me. A poignant reminder to those killed.

Inside the church was a very different story. I was immediately hit by the musty smell of the dead that permeated my every pore. There were a number of charred bodies laid out on a platform, the shrivelled remnants of bodies twisted in the grimace of death. The remains of one woman stuck in my mind, her arms bent in terror trying vainly to protect herself from impending death, her face frozen in a grotesque and ghoulish scream. It was a gut wrenchingly sickening sight to see. Such a sight seemed a wholly inappropriate form of commemoration and memorial.

The genocide should not be forgotten but the dead should at least be allowed to rest in peace. They should be remembered with dignity and there are many sites throughout the countryside that do just that. Whilst it is important never to forget what happened it is equally important to look forward to the future. The genocide is also about moving on and Rwanda is surmounting its problems with a determination worthy of support.

Its smiling people are wonderfully friendly. They have courage and warmth and yet there is an innocence to them that is not always so evident in other parts of Africa. Wide-eyed children ran excitedly from the fields and their houses, tripping over themselves to reach the road and greet me an outsider, a visitor to their country. Even the old smile and wave, seemingly genuinely pleased.

But it is not just the spirit of its people that Rwanda should be proud of but its fantastic wildlife, in particular chimpanzees and gorillas.

|

|

|