“Welcome to Syria,” beamed Bassam.

Short heavy set, slightly unshaven, with a thick dark moustache and mirror aviator-style Ray Bans, Basssam could easily have been cast as a villain in any gangster film. He, in looks at least, conformed to the ‘evil’ stereotype that some would have us believe of Syria. In fact, he was my guide and driver and could not have been more warm, friendly and generous. My initial reaction of Bassam was way off the mark and perhaps symptomatic of the poor image of the country as a whole. Seen from the outside Syria has a rough veneer, but this could not be more wrong, of its people at least.

I had been lured to Syria by its history and sights but notwithstanding the wealth of history on offer, what stands out in my memory is the people, their generosity and hospitality. Friendliness and hospitality were constant and continual throughout my short stay. The reputation of the government is questionable and not helped by the omnipresent posters and billboards of the Assad family but as a visitor you should separate the people from those that govern them – just as the Syrians politely do when meeting you.

My experiences were by no means unique. Arab hospitality is renowned worldwide and everyone takes pleasure in entertaining a guest, asking after one’s family and offering hospitality. Nowhere is this more evident than in Syria, which has a long tradition for generosity. In the nineteenth century Lady Jane Digby, who lived in Damascus for a number of years, talked of their “unbounded hospitality, respect for strangers or guests, good faith and simplicity of dealing amongst themselves, and a certain high bred politeness and unobtrusiveness.”

Bassam met me in Beirut from where wedrove north into Syria. The border, more than an arbitrary line on a map, changed everything, not least Bassam’s mood. He beamed his welcome, clearly proud of his country and happy to be home. With a combination of its green mountains, desert, the fertile Euphrates and the greatest collection of Roman and pre-Roman ruins to be found anywhere, Syria is a jewel in the crown of the Middle East. Bassam’s pride was not unfounded.

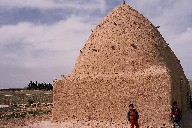

The first of Syria’s ancient monuments that I visited affirmed that impression. Imperious to the onslaught of time, Kerak des Chevaliers is both architecturally impressive – TE Lawrence described Kerak as “the finest castle in the world” – and historically important. In the mid twelfth century the Knights Hospitaller rebuilt the original fort into the imposing edifice that still stands defiantly today. Despite repeated sieges the fortress was never breached but ultimately given up.

It is easy to see why: the castle dominates the Homs Gap, assuring authority over inland Syria by controlling the flow of goods and people from the ports through to the interior. Although striking, I wish I had paid more attention in my crusader lectures back at College and lacking the imagination to rely on childhood images of knights in shining armour and pennants fluttering in the wind, the castle felt empty and hollow. With the wind whistling and buffeting around it was difficult to imagine its former glory. Instead the noble edifice provided shelter for sheep seeking shade, spectacular views and photo opportunities.

It was time to move on to Palmyra, the legendary city of palms, en route passing through Homs. The major boast of Homs, Syria’s third largest city, is oil. More specifically refinery, which Bassam quipped was the only refined thing about the city. Given Bassam’s jibe, I was not surprised to read that Homs is the butt of Syrian humour. Jokes about Homs and the people of Homs are frequently told and hugely enjoyed by the Syrians. I found such jokes not only reminiscent both in tone and humour of English jokes about the Irish but further evidence of the sense of fun of the Syrians, in defiance of their image abroad.

A Homsi joins the intelligence services. On the first day his superior officer is unsure what to do with the Homsi so he places him on the most basic of surveillance jobs telling him to report back every half an hour. Shortly after starting he gets a call from the Homsi, “Hello, sir. I am a good Homsi and am following the man as you asked. He is walking on the right hand side of the pavement and I am walking on the left.” Half an hour later he calls again, “Hello, sir. I am a good Homsi. He is in a restaurant. He is eating a kebab and I am eating chicken.” An hour later he calls form the bus station. “Hello, sir. I am a good Homsi. The subject took the bus to Damascus and I took the bus to Palmyra.”

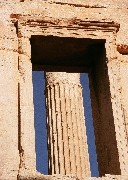

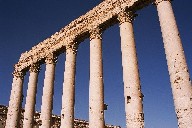

Palmyra is the stuff of legend, conjuring up images of caravans laden with silks and spices, and pictures of the enigmatic if redoubtable Queen Zenobia who so bewitched many an eighteenth century Romantic adventurer. The history of Palmyra goes back to at least the second millennium BC. An oasis town at the limit of the Anti Lebanon Mountains, it was an important staging post both on the Silk Road and between the Mediterranean and the Gulf. It prospered through charging heavy tolls and was an important frontier town between the Romans and the Persians, even being visited by Emperor Hadrian in AD 130. Palmyra reached its zenith a century later with the reign of Queen Zenobia, although her eventual defeat marked the end of Palmyra’s prosperity. The city was finally destroyed by an earthquake in 1089 and largely covered over by sand.

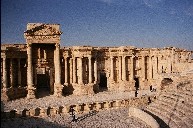

Today, Palmyra rises defiantly from the sands and surrounding palms, from which the city derives its name. After the monotony and emptiness of the desert, Palmyra was stunning and it was easy to see how Palmyra laid claim to being Syria’s prime historical attraction. The ruins are dominated by the gargantuan temple of Baal, an incredible feat of engineering by any standards. The great colonnade is the spine of ancient Palmyra.

What really thrilled me about Palmyra was not just my awe at the size and grandeur of the site but that it was very much a living monument. Families picnicked amongst the ruins, sharing coffee and swapping stories, a trio of girls dressed in jeans and western fashions danced around a small portable sound system. This might be sacrilege to Palmyra purists and those believing that the site should be left alone but for me it is not simply the preserve of archaeologists and foreign tourists but it is a Syrian monument.

A country born out of Roman, Greek, Byzantine and French cultures, Syria is a vibrant mixture of races who are all represented religiously, architecturally and culturally. Nowhere is this more apparent than the streets of Old Damascus, the oldest inhabited city in the world. Here, the stories of the Bible come magically to life, irrespective of your religious beliefs. “Damascus surpasses all other cities in beauty, and no description can do justice to its charms,” wrote Ibn Battutah, the 14th-century Moroccan traveller and travel writer par excellence.

Yet on arriving at the outskirts of Damascus, Ibn Battutah’s description seemed dated. Faded billboards advertising all the paraphernalia of modern life from washing machines, to cars, competed for space amongst the ugly breezeblock buildings. Sensing my disappointment as we sat in a crush of traffic and black exhaust fumes, Bassam urged me to be patient, “Wait. Wait for the Old City.”

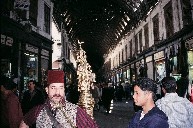

Bassam was not wrong. Entering the Hamidiyya souq, a vast market covered by a curved corrugated iron roof, pockmarked with holes that let in shafts of light, I was swept along by the tide of shoppers. Tall men wearing checked keffiyehs and brown cloaks ambled along absorbed in conversation, women shrouded and veiled in black searched for bargains, whilst toddlers trailed behind them and children licked ice cream sprinkled with a topping of pistachio. A man in tarboush (fez) and Turkish trousers stood resolutely amidst the tide, an eddy of people swirling around him, as he sold tamarind juice spiced with rose water.

My head was continually turning from side to side as my attention was caught again and again by the sheer variety of what was on offer. There was jewellery, shoes, backgammon sets, rugs, scarves, fabric and curved daggers. There were tiny stalls selling the most delicious cashew and pistachio nuts. The spice shops displayed cumin, coriander, saffron and cardamom in a visual and olfactory feast.

I emerged into sunlight and what remains of the triumphal arch that marks the remains of the Temple of Jupiter. The arch guards the gate to the majestic Ummayad mosque, one of the most magnificent buildings of Islam, second only to the mosques of Mecca and Medina. Its history is however unequalled. Battutah described the Umayyad Mosque as “the most magnificent mosque in the world”. Indeed it is a prestigious monument and despite the ravages of time it is still clear to see the sumptuousness of the materials used and the quality of decorations.

The marble white of the courtyard outside the mosque was dazzling in stark contrast to the black worn by the women. As children slid playfully on the marble floor I was struck at how the mosque’s role was not merely religious but a social gathering place. It was very much a part of society, something that the churches of England lost years ago.

East of the mosque, the Old City continued to be full of magic and charm with its bazaars, blind alleys, mosques and minarets, courtyards, street vendors, carts of almonds – green with furry skin that are crunchy and bitter to taste. Plunging into the tortuous alleys my senses were ignited by the heady aromas of bags of spices, brimming but never spilling, the sizzling smell of falafel and kebabs, the murmur of conversation and the burble of business and barter.

In these streets the modern world is left behind and history presses in on all sides. There is no bustle, no traffic, only worn streets that lazily wind their way between old, traditional houses. There is a lack of conformity and symmetry in the houses, each is individual and distinct, and in defiant contrast to the sameness and uniformity that characterises the new town. Walls slope, a riot of angles, leaning and wobbling, struggling for balance as if caught in freeze frame before being devoured by the earth.

Behind the walls and within the courtyard, family life goes on. Occasionally a door left ajar allows a sneak look into the world inside, the agreeable courtyards, neat and clean, swept daily, with orchids and a forest of potted plants. In many ways these Damascene homes are a metaphor for Syria as a whole – uninviting façade that conceal an inviting courtyard and many pleasant surprises.

I was so absorbed by the magic of Damascus that it was only hours later that I realised that my wanderings had taken me miles and my weary limbs had had enough. I sought the rejuvenating and revitalising attentions of Damascus's most famous hammam, the Al Nouri. Here, you can luxuriate in the steam, have a massage, a glass of tea and loll about on marble slabs. Even amongst the steam-filled chambers, all I encountered was helpfulness and politeness. After a fierce scrub-down, followed by a massage, I came away walking on air and ready for dinner.

I had been invited to dine with

Bassam and his family. Warmth and generosity does little to describe

the wonderful open-armed generosity of Bassam

and his family. I could not have been made to feel more welcome and part

of the family. So much so that by the end of the meal I was invited to

his sister’s, Rania’s, wedding. It was the quickest acceptance

to a wedding that I have ever made, not least because I cannot wait to

get back to Syria.

|

|

|