I had arrived in Timbuktu shaken but not stirred. Shaken by the incessant jarring and juddering of the road, unmoved by what I saw on arrival. There can be few names as evocative and few places that are as disappointing.

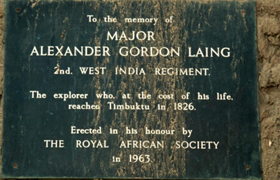

Timbuktu has long been associated with mysterious beauty, learning and above all wealth. René Caillié, the first European to return from Timbuktu alive in 1828 (the Scotsman Gordon Laing had preceded him by two years but died on his homeward journey) tried to force a more prosaic description upon popular awareness. Caillié wrote “I was amazed by the lack of energy, by the inertia that hung over the town…. A jumble of badly built houses ….ruled over by a heavy silence.” But few listened and the allure of Timbuktu lived on.

I had read some of Caillié’s descriptions and thus, unlike Dick Whittington, did not expect the streets to be paved with gold but nevertheless I was profoundly disappointed by what I saw. As I walked around, I became deeply depressed by the drabness of the grey stucco-covered mud brick houses, the sad neglect and the unsavoury smells. It was shabby, dirty and everywhere this dull grey sand. Not only did the sand lack warmth and colour but it grated in my teeth, which only further aggravated my disappointment with Timbuktu. So much so, that in spite of my reverence for explorers past, the obligatory tourist photo stop outside the houses of Gordon Laing and René Caillié did little to lighten my mood let alone salvage the situation.

Salt made Timbuktu wealthy; it gave it gold through trade. So much so that in the fourteenth century, the ruler of Mali, Mansa Musa, travelled across the Sahara to Mecca with an entourage of 40,000 people. Today, the Midas touch has gone and the gold has turned to sand. A worthless currency except for the youth of present day Timbuktu: toddlers push flip flops through the sand, older children play marbles throughout the streets, while the even older children, adolescents, rev their mopeds in circles in the sand trying to impress their belles.

Unable to derive such puerile pleasure from Timbuktu, I opted to spend the night in a nearby Tuareg camp in the desert. The Tuareg are the enigmatic nomads of the desert famed as lords of the great caravan routes along which flowed salt, slaves, and gold. They are the Blue Men of the Sahara, so-called for the deep indigo dyes used in their robes.

As with Timbuktu, the Tuaregs have been shrouded in mystery and myth for centuries. Fortunately there the similarities end, although my initial impressions were not encouraging. Looking awkward and ill at ease, a young Tuareg, Hussein was waiting for me by a small camel. Even with my limited knowledge of camels, I felt that this camel was pathetically small for my more-than-the-average-Tuareg weight. The unfortunate camel seemed to agree, bellowing and roaring his displeasure in Chewbacca-like fashion.

“La, la” (No, no) admonished Hussein as he tried to rearrange my feet across the ridge of my camel’s neck. Riding a camel with the Tuaregs was not as easy as I had thought. Already uncomfortable on the wooden Tuareg saddle, with its high pommel front and back, Hussein twisted my feet into grotesque positions, left foot first, and with both feet splayed outwards. What made it doubly uncomfortable is that I am pigeon-toed. As well as this discomfort, I had to endure the indignity of being led by Hussein, as if on a donkey ride on the beach. Just as I was thinking ‘how much worse is this going to get?’ his mobile phone rang.

What I did not realise in my vitriol against mobile phones was that it was the reinforcements announcing their arrival. For my camel it was the final straw, the straw that broke the camel’s back, literally. Its roars of displeasure had been answered, for silhouetted on the crest of a dune, with the sunset providing a dramatic backdrop, appeared a Tuareg on a majestic camel. My heart fluttered.

It fluttered again as the Tuareg rode confidently toward me. He dismounted with disarming ease and introduced himself as Sandy – how wonderfully apt. He told me to dismount and mount his much larger camel. The cavalry had arrived.

All my romantic notions sated, we headed west into the sunset. And what a sunset. The dying embers of the sun washed the horizon in a warm orange glow that gave a fiery richness to the palette of colours above. These began with most delicate of pale blues darkening into the inky depths of indigo, punctuated only by the brilliance of a lone, large bright star. Adding depth and poignancy to the exquisiteness of this canvas, was the quiet stillness and calm of the desert. A relief from the filth and noise of Timbuktu, the tranquillity, the twilight beauty, massaged away my disappointment.

The sun set, swiftly as its fashion in Africa, cloaking us in darkness. All I could see in front of me was the shadowy figure of Sandy. I worried, unnecessarily, about what he could see in front of him. In spite of the enveloping night he guided us unerringly through the rolling dunes and scrub, the peace only broken by the bizarrely comforting grinding of my camel chewing his cud and the occasional encouraging ‘Tscsshk’ from Sandy.

The comforting, flickering glow of fire heralded our arrival. We dismounted and Sandy welcomed me to his home. We sat, cross-legged, outside a low tent of hides, as tea was brought to us. A small charcoal burner, a silver tray decorated with Koranic verses, a small metal teapot and a couple of shot glasses.

Without a word, Sandy began to prepare the tea with meticulous care. His every movement was deliberate and with purpose. With the tea pot held two feet above a small shot glass, he expertly poured the tea back and forth from pot to glass several times. The he served the tea, which was hot, sweet, and strong.

Once the first pot was finished, Sandy began to rinse out the glasses for a second brew, careful not to spill any water.

“You are trying not to waste water?”

“No. There is a pump just over there.”

“Then why are you saving all the old water, not throwing it on the sand?”

“When the sand becomes damp or wet it attracts insects, beetles and scorpions.”

I had much to learn about life in the desert.

Life in the desert is a practical one that affords few luxuries. I asked Sandy if he had any pets, any dogs. He replied, “Cats, yes. Dogs, no. Dogs bark, they make noise. But especially they do not eat insects like cats.”

Our conversation continued into the night discussing the price of goats and camels – 25,000 CFA and 600,000 CFA respectively. We talked of the political system in Mali, the Tuareg revolts of the 90s and why they happened. Sandy was in no doubt it was because the government had forced the Tuaregs to live “derrière la porte”. Meanwhile the passage of stars continued silently overhead.

In the morning I awoke nervous that perhaps the darkness had hidden a multitude of sins and that my romantic notions had got the better of me. Or perhaps I had been so desperate to escape Timbuktu that anything would seem good by comparison.

Thankfully, my surrounds were as magical as I had imagined them in the twilight gloom. The women were ‘faire la cuisine’, the men prostrating themselves in prayer and the children rearranging the camel saddles into position and then mounting them and rocking them into a gallop and an imaginary race. A new day had dawned in the life of this Tuareg family and I felt privileged to be a part of it. I was sad to leave later that morning and hence said “À la prochaine” with real meaning.

It was not just a courteous farewell, but heartfelt. I had thoroughly enjoyed my time with Sandy and the Tuaregs, which is more than can be said for Timbuktu.

|

|

|